Welcome to the Brains Weblog’s Symposium collection on the Cognitive Science of Philosophy. The goal of the collection is to look at using various strategies to generate philosophical perception. Every symposium is comprised of two elements. Within the goal publish, a practitioner describes their use of the tactic underneath dialogue and explains why they discover it philosophically fruitful. A commentator then responds to the goal publish and discusses the strengths and limitations of the tactic.

On this symposium, Paul Conway (College of Portsmouth) argues that, though ethical dilemmas don’t inform us whether or not laypeople are deontologists or utilitarians, they can be used to review the psychological processes underlying ethical judgment. Man Kahane (College of Oxford) offers commentary, suggesting that the ethical dilemmas we care about go far past trolley-style situations.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

What Do Ethical Dilemmas Inform Us?

Paul Conway

Think about you might kill a child to avoid wasting a village or inject individuals with a vaccine you realize will hurt a couple of individuals however save many extra lives. Think about a self-driving automotive might swerve to kill one pedestrian to forestall it from hitting a number of extra. Suppose as a health care provider in an overburdened healthcare system you’ll be able to flip away a difficult affected person to dedicate your restricted time and assets to saving a number of others. These are examples of sacrificial dilemmas, cousins to the well-known trolley dilemma the place redirecting a trolley to kill one particular person will save 5 lives.

Philosophers, scientists, and most people share a fascination with such dilemmas, as they function not solely in philosophical writing and scientific analysis, but in addition in style tradition, together with The Darkish Knight, The Good Place, M*A*S*H*, and Sophie’s Selection. Thanos additionally contemplated a sacrificial dilemma–kill half the inhabitants to create a greater world–and there are reams of humorous dilemma memes on-line. So, dilemmas have struck a chord inside and past the academy.

But, questions come up as to what dilemmas truly inform us. Tutorial work on dilemmas originated with Philippa Foot (1967), who used dilemmas as thought experiment instinct pumps to argue for considerably arcane phenomena (e.g., the doctrine of double impact, the argument that hurt to avoid wasting others is permissible as a facet impact however not focal purpose). Nevertheless, subsequent theorists started deciphering sacrificial dilemmas by way of utilitarian ethics targeted on outcomes and deontological ethics targeted on rights and duties. Sacrificing a person violates most interpretations of (for instance) Kant’s (1959/1785) categorical crucial by treating that particular person as a method to an finish/with out dignity. But, saving extra individuals maximizes outcomes, in keeping with most interpretations of utilitarian or consequentialist ethics, as described by Bentham (1843), Mill (1998/1861), and Singer (1980), amongst others.

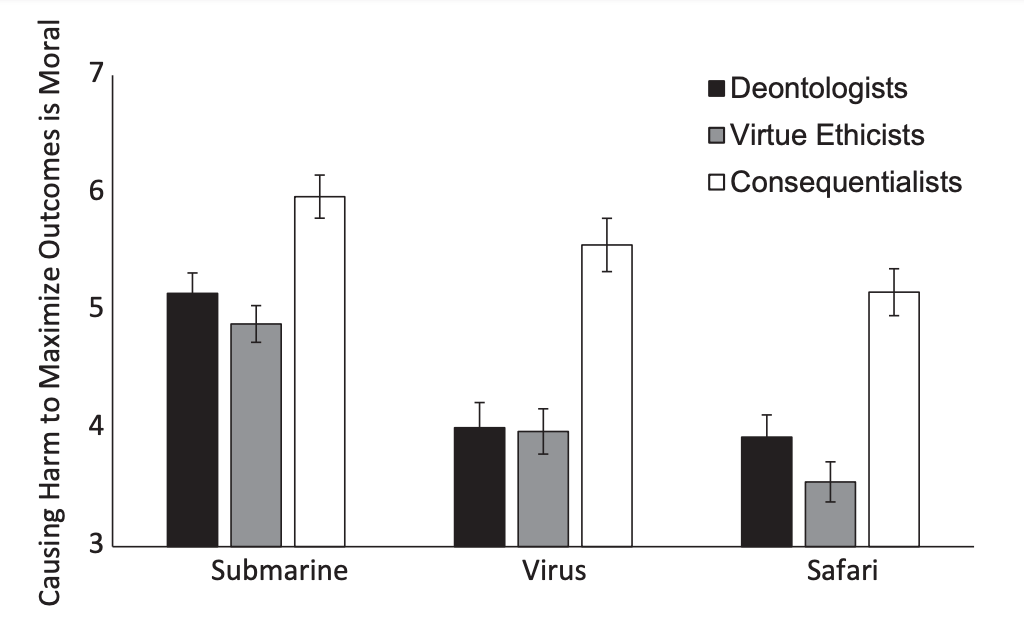

Some theorists have taken dilemma responses as a referendum on philosophical positions. On the floor, this may occasionally appear affordable–in spite of everything, philosophers who establish as consequentialist are inclined to endorse sacrificial hurt extra usually than those that establish as deontologists or advantage ethicists. For instance, Fiery Cushman & Eric Schwitzgebel discovered this sample when assessing philosophical leanings and dilemma responses of 273 individuals holding an M.A. or Ph.D. in philosophy, printed in Conway and colleagues (2018). Additionally, Nick Byrd discovered that endorsement of consequentialist (over deontological ethics) correlated with selecting to drag the change on the trolley downside in two completely different research that recruited philosophers (2022).

Determine 3: Philosophers who establish as consequentialist (just like utilitarianism) endorse sacrificial hurt extra usually than these figuring out as deontologists or advantage ethicists (Conway et al., 2018).

If utilitarian philosophers endorse utilitarian sacrifice, then certainly different individuals endorsing utilitarian sacrifice should endorse utilitarian philosophy, the reasoning goes. Presumably, individuals who reject sacrificial hurt should endorse deontological philosophy. In spite of everything, some researchers argue persons are fairly constant when making such judgments (e.g., Helzer et al., 2017).

Nevertheless, it is a non sequitur. It assumes that philosophers and laypeople endorse judgments for a similar causes and that the one causes to endorse or reject sacrificial hurt replicate summary philosophical rules. It additionally inappropriately reverses the inference: sacrificial judgments are utilitarian as a result of they align with utilitarian philosophy; that doesn’t imply that each one judgments described as utilitarian replicate solely adherence to that philosophy.

One want solely take essentially the most cursory look on the psychological literature on decision-making to notice that many selections human beings make don’t replicate summary adherence to rules (e.g., Kahneman, 2011). As an alternative, selections usually replicate a posh mixture of processes.

For an analogy, think about an individual selecting between shopping for a home or renting an residence. The choice they arrive at would possibly replicate many components, together with calculations about measurement and price and site of every possibility, but in addition intuitive emotions about how a lot they like every possibility—importantly, how a lot they like every possibility relative to at least one one other (some extent we’ll return to).

Certain, some individuals would possibly persistently favor homes and different persistently favor residences, however many individuals would possibly begin off residing in an residence and afterward transfer to a home when their household grows. Does anybody assume that such selections replicate inflexible adherence to an summary precept reminiscent of ‘apartmentness’? Likewise, some well-known individuals persistently reside in homes (Martha Stewart?) and others in residences (Seinfeld?)—does that imply that everybody selecting one or the opposite makes that selection for a similar cause (e.g., they’re the star of a success TV present set in New York)? Furthermore, a home continues to be a home irrespective of the rationale somebody selects it, simply as a sacrificial determination that maximises outcomes is in step with utilitarian philosophy even when somebody chooses it for lower than noble causes.

The issues deciphering dilemmas deepened when researchers stared noting the sturdy tendency for delinquent character traits, reminiscent of psychopathy, to foretell acceptance of sacrificial hurt (e.g., Bartels & Pizarro, 2011). Do such findings counsel that psychopaths genuinely care concerning the well-being of the most individuals, and will in actual fact be ethical paragons? Or do such findings counsel that sacrificial dilemmas fail to measure the issues philosophers care about in spite of everything (see Kahane et al., 2015)?

If dilemma responses needs to be handled as a referendum on adherence to summary philosophical rules, then clearly the sacrificial dilemma paradigm is damaged.

Nevertheless, there’s one other strategy to conceptualize dilemma responses: from a psychological perspective. Returning to the purpose concerning the position of psychological mechanisms concerned in decision-making, reminiscent of residence searching, one can ask the query, What psychological mechanisms give rise to acceptance or rejection of sacrificial hurt?

Be aware this query shifts away from the query of endorsement of summary philosophy and focuses as a substitute on understanding judgments. In different phrases, as a substitute of attempting to know summary ‘apartmentness,’ researchers ought to ask, Why did this particular person choose this residence over that home?

This angle was first popularized by a Science paper printed by Greene and colleagues on the flip of the millennium. They gave dilemmas to individuals in an fMRI scanner, and argued for a twin course of mannequin of dilemma decision-making: intuitive, emotional reactions to inflicting hurt inspire selections to reject sacrificial hurt, whereas logical cognitive processing about outcomes inspire selections to simply accept sacrificial hurt (thereby maximizing outcomes).

In keeping with this argument, individuals greater in emotional processing, reminiscent of empathic concern, aversion to inflicting hurt, and agreeableness, are inclined to reject sacrificial hurt (e.g., Reynolds & Conway, 2018), whereas individuals greater in logical deliberation, reminiscent of cognitive reflection take a look at efficiency, have a tendency to simply accept sacrificial hurt (e.g., Patil et al., 2021; Byrd & Conway, 2019). There’s lots extra proof, a few of it a bit combined, however general, the image from a whole lot of research roughly aligns with this fundamental cognitive-emotional distinction, although proof suggests roles for different essential processes as effectively.

Importantly, the twin course of mannequin suggests there is no such thing as a one-to-one match between judgment and course of. As an alternative, a given judgment individuals arrive at displays the relative power of those processes. Simply as somebody who sometimes would possibly select an residence could get swayed by a very good home, sacrificial judgments theoretically replicate the diploma to which emotional aversion to hurt competes with deliberation about outcomes. Will increase or reductions of both course of ought to have predictable impacts on sacrificial judgments.

Due to this fact, it makes good sense why psychopathy and different delinquent character traits ought to predict elevated acceptance of sacrificial hurt: such traits replicate diminished emotional concern for others’ struggling, a ‘callous disregard for others’ well-being.’ Therefore, individuals excessive in such traits ought to really feel low motivation to reject sacrificial hurt—even when they don’t essentially really feel explicit concern for the larger good.

This argument is corroborated by modelling approaches, reminiscent of course of dissociation (Conway & Gawronski, 2013) and the Penalties, Norms, Inaction (CNI) Mannequin (Gawronski et al., 2017). Relatively than analyzing responses to sacrificial dilemmas the place inflicting hurt all the time maximizes outcomes, these approaches systematically differ the outcomes of hurt—generally harming individuals (arguably) fails to maximise outcomes.* As an alternative of analyzing strict selections, these approaches analyse patterns of responding: some individuals systematically reject sacrificial hurt no matter whether or not doing so maximizes outcomes (in step with deontological ethics). Different individuals persistently maximize outcomes, no matter whether or not doing so requires inflicting hurt (in step with utilitarian ethics). Some individuals easy refuse to take any motion for any cause, no matter hurt or penalties (in step with basic inaction).

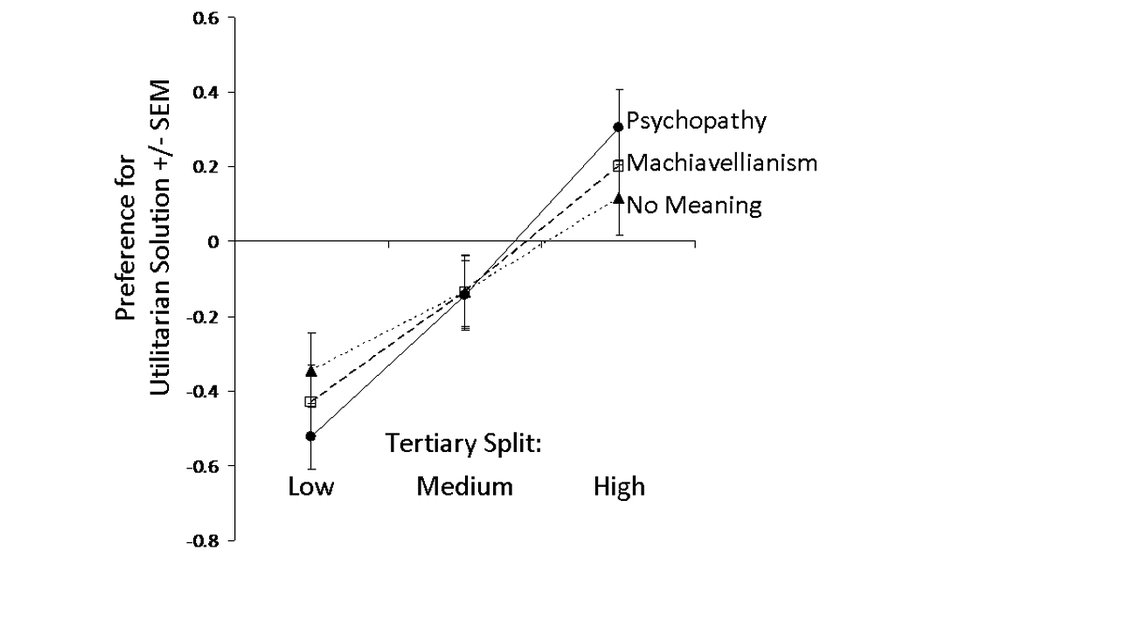

Research measuring delinquent character traits utilizing modelling approaches present an attention-grabbing sample. As predicted, psychopathy and different delinquent traits certainly predict diminished rejection of sacrificial hurt (i.e., low deontological responding)—however they don’t predict elevated utilitarian responding—fairly the other. Delinquent traits additionally predict diminished utilitarian responding (simply to a lesser diploma than diminished deontological responding, Conway et al., 2018; Luke & Gawronski, 2021).

In different phrases, individuals excessive in psychopathy leap on the alternative to trigger hurt for the flimsiest cause that provides them believable deniability—relatively than demonstrating concern for utilitarian outcomes.

In the meantime, individuals who care deeply about morality, reminiscent of these excessive in ethical id (caring about being an ethical particular person, Aquino & Reed, 2002), deep ethical conviction that hurt is incorrect (Skitka, 2010), and aversion to witnessing others endure (Miller et, al., 2014) concurrently rating excessive in each aversion to sacrificial hurt and considerations about outcomes—in different phrases, they appear to indicate a real dilemma: pressure between deontological and utilitarian responding (Conway et al., 2018; Reynolds & Conway, 2018; Körner et al., 2020).

Importantly, most of those findings disappeared when taking a look at common sacrificial judgments the place inflicting hurt all the time maximizes outcomes—such judgments power individuals to finally choose one or the opposite possibility, shedding the power to check any pressure between them. Some individuals is likely to be extraordinarily enthusiastic about each a home and residence, but finally have to decide on only one—different individuals is likely to be unenthusiastic about both selection, but additionally should finally select one. What issues isn’t a lot the selection they make, however the advanced psychology behind their selection. That is value learning, even when it doesn’t replicate some summary precept.

Therefore, it might be too quickly to ‘throw the infant out with the bathwater’ and abandon dilemma analysis as meaningless or uninteresting. Dilemma judgments replicate a posh mixture of psychological processes, few of which align with philosophical rules, however a lot of that are fascinating in their very own proper. Dilemmas, like different psychological decision-making analysis, present a singular window into the psychological processes individuals use to resolve ethical conflicts (Cushman & Greene, 2012). Dilemmas don’t replicate adherence to philosophical rules—researchers have developed different methods to evaluate such issues (Kahane et al., 2018)—however they continue to be essential to review.

It’s because sadly, whereas the trolley dilemma itself is only hypothetical, sacrificial dilemmas happen in the actual world on a regular basis. When police use power in service of the general public good, judges sentence harmful offenders to guard victims, when dad and mom self-discipline youngsters to show them helpful classes, or professors fail college students who haven’t accomplished work to protect disciplinary requirements and guarantee {qualifications}–every of those conditions parallels sacrificial dilemmas.** As decision-makers face many advanced sacrificial situations in actual life, which frequently replicate issues of life or demise, it’s vital to know the psychology concerned.

Consider an administrator of a hospital overwhelmed by COVID deciding who shall be sacrificed to avoid wasting others—would you like that particular person to be excessive in ethical id, struggling between two ethical impulses, or excessive in psychopathy, largely detached both approach? The psychological processes concerned in dilemma decision-making are very important for society to review, no matter any philosophical connotations they (don’t sometimes) have.

Notes

*The CNI mannequin additionally manipulates whether or not motion harms or saves a focal goal.

**Assuming truthful and even handed utility of police power, assuming judges make use of utilitarian relatively than punitive approaches to sentencing, assuming parental self-discipline is well-meaning and effectively calibrated to educating helpful classes, and so forth. Little question actuality is extra advanced than this, however the basic framework of dilemmas nonetheless permeates many essential selections.

_____________

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Commentary: Why Dilemmas? Which Dilemmas?

Man Kahane

________

We generally face ethical dilemmas: conditions the place it’s extremely onerous to know what’s the correct factor to do. One cause why ethical philosophers develop elaborate moral theories like utilitarianism or deontology is in an effort to give us principled methods to cope with such troublesome conditions. When philosophers argue over which moral concept or precept is true, they often think about what their theories would inform us to do in varied ethical dilemmas. However they usually additionally think about how these rules would apply in thought experiments: fastidiously designed hypothetical situations (which may be outlandish however needn’t be) that enable us to tease aside varied doable ethical components. Thought experiments aren’t meant to be troublesome—in actual fact, if we wish to use them to check competing ethical rules, the ethical query posed by a thought experiment needs to be pretty straightforward to reply. What is tough—what requires philosophical work—is to establish ethical rules that might make sense of our assured intuitions about varied thought experiments and real-life circumstances.

The well-known trolley circumstances have been first launched by Philippa Foot and Judith Jarvis Thomson as thought experiments, not as dilemmas. Foot discovered it apparent that we must always change a runaway practice to a special monitor if this might result in one dying as a substitute of 5. She was attempting to make clear what was a extremely controversial ethical challenge within the Sixties (and, alas, stays controversial)—whether or not abortion is permissible—not within the ethics of sacrificing individuals in railway (or for that matter, army or medical) emergencies. The so-called trolley downside isn’t involved with whether or not it’s alright to change the runaway practice or, in Thomson’s variant, to push somebody off a footbridge to cease such a practice from killing 5 (Thomson and most of the people assume that’s clearly incorrect), however to establish a believable ethical precept that might account for our divergent ethical intuitions about these structurally comparable circumstances.

Foot would have most likely discovered it very stunning to listen to that her incredible situation is now a (and even the) key approach through which psychologists research ethical decision-making. Her thought experiment a few runaway trolley has by now been utilized in numerous ‘actual’ experiments. For instance, psychologists have a look at how individuals will reply to such situations the place they’re drunk, or sleep disadvantaged, or have borderline character dysfunction, or when these situations are introduced in a tough to learn font or when the individuals concerned are household family or overseas vacationers and even (in some research I’ve been concerned in) aren’t individuals in any respect however animals! Quite a lot of attention-grabbing information has been gathered on this approach however, weirdly sufficient, it’s however not but so clear what all of that may train us, not to mention why trolley situations are taken to be so central to the research of the psychology of ethical decision-making.

There’s one reply to this query that each I and Paul Conway reject. It goes like this. A central debate in ethical philosophy is between utilitarians (who search to maximise happiness) and deontologists (who consider in guidelines that forbid sure type of acts). Utilitarians and deontologists give opposing replies to sure trolley situations: utilitarians will all the time sacrifice some to avoid wasting the larger quantity whereas deontologists assume some methods of saving extra lives are incorrect. So by asking atypical individuals whether or not they would sacrifice one to avoid wasting 5 we are able to discover out the extent to which individuals comply with utilitarian or deontological rules. However it is a poor rationale for doing all of these psychological experiments. To start with, as Paul factors out, the overwhelming majority of individuals don’t actually method ethical questions by making use of something resembling a concept. And though it’s true that utilitarians method these dilemmas in a particular approach, the trolley situations weren’t actually devised to distinction utilitarianism and deontology, and are only one type of (pretty peculiar) case the place utilitarianism clashes with various theories (Kahane et al., 2015; Kahane, 2015; Kahane et al., 2018). For instance, utilitarians additionally sometimes maintain that we must always ourselves make nice sacrifices to forestall hurt to distant strangers, wherever they might be (e.g. by donating most of our earnings to charities aiding individuals in want in creating international locations), whereas deontological theories usually see such sacrifices as at greatest non-compulsory. However, as Paul additionally agrees, willingness to push somebody else off a footbridge inform us little or nothing about somebody’s willingness to sacrifice their very own earnings, or well-being, and even life, for the sake of others (Everett & Kahane, 2020).

A greater reply, which Paul favours, is that by learning how atypical individuals method these situations, we are able to uncover the processes that underlie individuals ethical decision-making. It’s exactly as a result of individuals usually don’t make ethical selections by making use of express rules, and since what actually drives such selections is commonly unconscious, that learning them utilizing psychological strategies (and even purposeful neuroimaging) is so attention-grabbing. In keeping with one influential concept, when individuals reject sure methods of sacrificing one to avoid wasting a larger quantity (for instance, by pushing them off a footbridge), these ethical judgments are pushed by emotion (Greene et al. 2004). Once they endorse such sacrifice, this may be (as within the case of psychopaths) simply because they lack adverse emotional response most of us should straight harming others, however it can be as a result of individuals have interaction their capability for effortful reasoning. That is an intriguing concept that Paul has executed a lot to help and develop (see e.g. Conway & Gawronski, 2013). As a concept of what goes in individuals’s brains after they response to trolley situations, it appears to me nonetheless incomplete. What, for instance, are individuals doing precisely after they have interaction in effortful pondering and determine that it’s alright to sacrifice one for the larger good? We’ve already agreed they aren’t making use of some express concept reminiscent of utilitarianism. Presumably in addition they don’t want a terrific effort to calculate that 5 is larger than 1—as if those that don’t endorse such sacrifices are arithmetically challenged! But when the cognitive effort is just that wanted to beat a powerful rapid instinct or emotion in opposition to some selection, this doesn’t inform us something very stunning. Somebody would possibly equally have to make such an effort so as, for instance, to override their rapid motivation to assist individuals in want and selfishly stroll away from, say, the scene of a practice wreck (Kahane, et al. 2012; Everett & Kahane, 2020).

Maybe a extra essential query is what we actually study human ethical decision-making if, say, one type of response to trolley situations is (let’s assume) primarily based in emotion and one other primarily based in ‘cause’. There’s one controversial reply to this additional query that Paul doesn’t say a lot about. We earlier rejected the image of atypical individuals as lay ethical philosophers who apply express theories to handle dilemmas. However there’s one thing to be mentioned for the reverse view: that ethical philosophers are extra just like laypeople than they appear. Philosophers do have their theories and rules, however it is likely to be argued that these finally have their supply in psychological reactions of the type shared with the people. Kant could attraction to his Categorical Crucial to clarify why it’s incorrect to push a person off a footbridge, however maybe the actual cause he thinks that is incorrect is that he feels a powerful emotional aversion to this concept. And if moral theories have their roots in such psychological reactions, maybe we are able to consider these theories by evaluating these roots. Specifically, utilitarianism could appear to come back off higher if its psychological supply is reasoning whereas opponent views are actually constructed on an emotional basis, or no less than on rapid intuitions which might be, at greatest, dependable solely in slender contexts (see e.g. Greene, 2013). This model of argument has generated lots of debate. Right here I’ll simply level again to some issues I already mentioned. If when individuals who endorse sacrificial selections ‘assume tougher’ they’re simply overcoming some sturdy instinct, this leaves it totally open whether or not they ought to overcome it. Extra importantly, as we noticed, trolley situations seize only one particular implication of utilitarianism (its permissive perspective to sure dangerous methods of selling the larger good). However it leaves it totally open how, for instance, individuals arrive at judgments about self-sacrifice or about concern for the plight of distant strangers. Actually, the proof means that such judgments are pushed by completely different psychological processes.

Paul affords one other justification for specializing in trolley-style situations. We will neglect about philosophers and their theories. The actual fact is that individuals truly recurrently face ethical dilemmas, and it’s essential to know the psychological processes in play after they attempt to resolve them. This appears believable sufficient. However though some psychologists (not Paul) generally use ‘ethical dilemmas’ to simply imply trolley-style situation, there are very many varieties of ethical dilemmas—and as we noticed, some classical trolley situations aren’t even dilemmas, correctly talking! Ought to we preserve a promise to a good friend if this can hurt a 3rd occasion? Ought to we ship our kids to non-public colleges that many different dad and mom can’t afford? Ought to we go on that luxurious cruise as a substitute of donating all this cash to charities that save lives? It’s uncertain (or no less than must be proven) that the psychology behind peculiar trolley circumstances actually tells us a lot about these very completely different ethical conditions. If we wish to perceive the psychological of ethical dilemmas we have to forged a a lot wider web.*

I don’t assume Paul needs to say that by learning trolley situations, we are able to perceive ethical dilemmas normally. He relatively says that there’s a class of ethical dilemma that individuals in actual fact face in sure contexts—particularly army and medical ones—which is effectively value learning on the psychological stage. This appears proper, but when such circumstances don’t actually inform us a lot about grand philosophical disputes, nor maintain the important thing to the psychology of ethical decision-making (as many psychologists appear to imagine), and even simply to the psychology of ethical dilemmas, then do trolley actually deserve this a lot consideration? Why spend all that effort learning individuals’s responses to those farfetched conditions relatively than to the quite a few different ethical dilemmas individuals face? Furthermore, even when we wish to uncover the psychology of this type of precise selection scenario, why herald runaway trains as a substitute of circumstances that truly resemble such (fairly uncommon) real-life conditions. Docs generally have to make tragic selections however a health care provider who actively killed a affected person to avoid wasting 5 others will merely be committing homicide. Lastly, whereas it can little doubt be attention-grabbing to find the psychological processes and components that form selections in real-life sacrificial selections, it will be good to know what precisely we’re purported to do with this information. Will it, particularly, assist us make higher selections after we face such dilemmas? However this takes us proper again to the tantalising hole between ‘is’ and ‘ought’, and to these pesky moral theories we thought we’d left behind…

Notes

* See Nguyen et al. (2020) for an enchanting evaluation of 100,000 ethical dilemmas culled from the ‘Am I the Asshole’ subreddit—few of those are even remotely just like trolley situations.

___

* * * * * * * * * * * *

References

___________

Aquino, Okay., & Reed, I. I. (2002). The self-importance of ethical id. Journal of Character and Social Psychology, 83, 1423-1440.

Bartels, D. M., & Pizarro, D. A. (2011). The mismeasure of morals: Delinquent character traits predict utilitarian responses to ethical dilemmas. Cognition, 121, 154–161.

Bentham, J. (1843). The Works of Jeremy Bentham (Vol. 7). W. Tait.

Byrd, N. (2022). Nice Minds don’t Suppose Alike: Philosophers’ Views Predicted by Reflection, Training, Character, and Different Demographic Variations. Overview of Philosophy and Psychology.

Byrd, N., & Conway, P. (2019). Not all who ponder depend prices: Arithmetic reflection predicts utilitarian tendencies, however logical reflection predicts each deontological and utilitarian tendencies. Cognition, 192, 103995.

Caviola, L., Kahane, G., Everett, J., Teperman, E., Savulescu, J., and Faber, N. (2021). Utilitarianism for animals, Kantianism for individuals? Harming animals and people for the larger good. The Journal of Experimental Psychology: Basic, 150(5), 1008-1039.

Conway, P., & Gawronski, B. (2013). Deontological and utilitarian inclinations in ethical decision-making: a course of dissociation method. Journal of Character and Social Psychology, 104, 216-235.

Conway, P., Goldstein-Greenwood, J., Polacek, D., and Greene, J. D. (2018). Sacrificial utilitarian judgments do replicate concern for the larger good: Clarification through course of dissociation and the judgments of philosophers. Cognition, 179, 241-265.

Cushman, F., & Greene, J. D. (2012). Discovering faults: How ethical dilemmas illuminate cognitive construction. Social neuroscience, 7(3), 269-279.

Everett, J. and Kahane, G. (2020). Switching tracks: A multi-dimensional mannequin of utilitarian psychology. Developments in Cognitive Sciences, 24(2), 124-134.

Foot, P. (1967). The issue of abortion and the doctrine of double impact. Oxford Overview, 5, 5–15.

Gawronski, B., Armstrong, J., Conway, P., Friesdorf, R., & Hütter, M. (2017). Penalties, norms, and generalized inaction in ethical dilemmas: The CNI mannequin of ethical decision-making. Journal of Character and Social Psychology, 113, 343-376.

Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). The neural bases of cognitive battle and management in ethical judgment. Neuron, 44, 389–400.

Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in ethical judgment. Science, 293, 2105–2108.

Greene, Joshua (2013). Ethical Tribes: Emotion, Purpose, and the Hole Between Us and Them. Penguin Press.

Helzer, E. G., Fleeson, W., Furr, R. M., Meindl, P., & Barranti, M. (2017). As soon as a utilitarian, persistently a utilitarian? Analyzing principledness in ethical judgment through the robustness of particular person variations. Journal of Character, 85, 505-517.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Considering, quick and sluggish. Macmillan.

Kant, I. (1959). Basis of the metaphysics of morals (L. W. Beck, Trans.). Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill. (Authentic work printed 1785)

Kahane, G., Wiech, Okay., Shackel, N., Farias, M., Savulescu J. and Tracey, I. (2012). The neural foundation of intuitive and counterintuitive ethical judgement. Social, Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(4), 393- 402.

Kahane, G., Everett, J. A., Earp, B. D., Farias, M., & Savulescu, J. (2015). ‘Utilitarian’ judgments in sacrificial ethical dilemmas don’t replicate neutral concern for the larger good. Cognition, 134, 193-209.

Kahane, G. (2015). Facet-tracked by trolleys: Why sacrificial ethical Dilemmas inform us little (or nothing) about utilitarian judgment. Social Neuroscience, 10(5), 551-560.

Kahane, G., Everett, J. A., Earp, B. D., Caviola, L., Faber, N. S., Crockett, M. J., & Savulescu, J. (2018). Past sacrificial hurt: A two-dimensional mannequin of utilitarian psychology. Psychological Overview, 125(2), 131.

Körner, A., Deutsch, R., & Gawronski, B. (2020). Utilizing the CNI mannequin to research particular person variations in ethical dilemma judgments. Character and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(9), 1392-1407.

Luke, D. M., & Gawronski, B. (2021). Psychopathy and ethical dilemma judgments: A CNI mannequin evaluation of private and perceived societal requirements. Social Cognition, 39, 41-58.

Mill, J. S. (1998). Utilitarianism (R. Crisp, Ed.). New York, NY: Oxford College Press. (Authentic work printed 1861)

Miller, R. M., Hannikainen, I. A., & Cushman, F. A. (2014). Dangerous actions or unhealthy outcomes? Differentiating affective contributions to the ethical condemnation of hurt. Emotion, 14(3), 573.

Nguyen, T. D., Lyall, G., Tran, A., Shin. M., Carroll, N. G., Klein, C., Xie, L. (2022). Mapping matters in 100,000 real-life ethical dilemmas. ArXiv preprint arXiv:2203.16762

Patil, I., Zucchelli, M. M., Kool, W., Campbell, S., Fornasier, F., Calò, M., … & Cushman, F. (2021). Reasoning helps utilitarian resolutions to ethical dilemmas throughout various measures. Journal of Character and Social Psychology, 120(2), 443.

Reynolds, C. J., & Conway, P. (2018). Not simply unhealthy actions: Affective concern for unhealthy outcomes contributes to ethical condemnation of hurt in ethical dilemmas. Emotion.

Singer, P. (1980). Utilitarianism and vegetarianism. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 325-337.

Skitka, L. J. (2010). The psychology of ethical conviction. Social and Character Psychology Compass, 4(4), 267-281.