When Nietzsche weighed our human notion of truth, he regarded it as “a movable host of metaphors, metonymies, and anthropomorphisms: in brief, a sum of human relations which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished.” That is true of reality within the human world, and that is the place science and society differ. The disparity is the rationale why the scientific perspective can provide such gladsome calibration and consolation for our human struggles.

On this planet of science, we endeavor to uncover basic legal guidelines and elemental truths detached to our opinions of them — these selfsame truths and legal guidelines that made us and govern {the electrical} impulses coursing by means of our cortices at 100 meters per second to forge the thought-patterns of opinion. However within the human world the place we reside, we swirl within the movable host of human relations and rationalizations, vaguely conscious that there is no such thing as a common reality and due to this fact no common good, as a result of each utopia is constructed on another person’s again. We devise frameworks for righting our relationships, which we name morality, however in our helpless confusion about what goodness is, we too readily mistake certainty for truth and self-righteousness for truth, then lash each other with our certitudes and rightneousnesses, mistaking the lashing for the sunshine of morality.

When our species was youthful and extra scared of actuality, myths and religions have offered the consolation of straightforward causalities and straightforward moralities to salve the confusions of complexity. However because the epoch of scientific discovery started disproving a few of these sacred certainties — first ejecting us from the placid airplane of the flat Earth, then from our self-soothing centrality within the Photo voltaic System, then from our grandiose exceptionalism within the order of residing issues, then from our galactic exceptionalism — the ethical certitudes about goodness additionally got here unloosed, for they too had been constructed upon the identical self-righteous basis because the outdated delusions in regards to the geometry of the universe and the immutability of life-forms.

The dazzling-minded Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919–February 8, 1999) took up these questions in her play Above the Gods — considered one of two Platonic dialogues she wrote within the Eighties, later included within the posthumous Murdoch anthology Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature (public library), which stays one of many best works of writing and pondering I’ve encountered.

Set in Athens within the late fifth century B.C. and structured as a dialog between a sixty-something Socrates, a twenty-something Plato, and 4 fictional Greek youths, the dialogue tussles with the query of whether or not the age of science has knelled the dying toll of faith and, in that case, the place this leaves our seek for reality and our eager for goodness — that elemental starvation for the final word which means of actuality, for our duty to actuality.

When Murdoch’s Socrates observes {that a} distinction between faith and morality is but to be made, with out which the central query of actuality and reality can’t be answered, an impassioned Plato responds:

Faith isn’t only a feeling, it isn’t only a speculation, it’s not like one thing we occur to not know, a God who would possibly maybe be there isn’t a God, it’s received to be obligatory, it’s received to make sure, it’s received to be proved by the entire of life, it’s received to be the magnetic centre of all the pieces.

And but this more-than-feeling goals at one thing past faith, past even express information, on the heart of which is the thought — the existence — of goodness:

In a manner, goodness and reality appear to come back out of the depths of the soul, and once we actually know one thing we really feel we’ve all the time identified it. But additionally it’s terribly distant, farther than any star… past the world, not within the clouds or in heaven, however a lightweight that reveals the world, this world, because it actually is… Despite all wickedness, and in all distress, we’re sure that there actually is goodness and that it issues completely.

Goodness, in Murdoch’s pretty conception, emerges as each object and background, each knower and identified. This renders moot the objectifying query, voiced by considered one of Plato’s sparring companions — a younger Sophist — of the place goodness resides in relation to actuality: both exterior us, present in one thing like a god, or inside us, as an inside picture we consult with. Observing that it’s each inside and outdoors, Murdoch’s Plato responds:

After all Good doesn’t exist like chairs and tables, it’s not… both exterior or inside. It’s in our complete way of life, it’s basic like reality. If we have now the thought of worth we essentially have the thought of perfection as one thing actual… Folks know that good is actual and absolute, not non-obligatory and relative, all their life proves it. And after they select false items they actually know they’re false. We will assume all the pieces else away out of life, however not worth, that’s within the very floor of issues.

The query of goodness permeates Murdoch’s complete physique of labor, however she plumbs this explicit facet of it — its bearing on reality and morality, lensed by means of Plato — in better depth in an essay titled On “God” and “Good,” additionally included in Existentialists and Mystics. With an eye fixed to the connection between the great and “the actual which is the correct object of affection, and of information which is freedom,” she considers what it takes for us to purify our consideration as a way to soak up actuality by itself phrases, unalloyed with our attachments and concepts.

What it takes, she suggests, is “one thing analogous to prayer, although it’s one thing troublesome to explain, and which the upper subtleties of the self can typically falsify” — not some “quasi-religious meditative method,” however “one thing which belongs to the ethical lifetime of the atypical individual.” Half a century after the existentialist and mystic Simone Weil liberated this uncooked mindfulness from the strict captivity of faith together with her pretty remark that “attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer,” for it “presupposes religion and love,” Murdoch writes:

The thought of contemplation is difficult to know and preserve in a world more and more with out sacraments and ritual and wherein philosophy has (in lots of respects rightly) destroyed the outdated substantial conception of the self. A sacrament offers an exterior seen place for an inside invisible act of the spirit.

Beholding magnificence in nature and in artwork, Murdoch argues, can function a form of sacrament for the spirit — the expertise offers (in considered one of her loveliest phrases, and one of many loveliest ideas ever dedicated to phrases) “an occasion for unselfing.” However this expertise, she cautions, shouldn’t be simply prolonged into issues of individuals and actions — the issues morality goals to barter — “since readability of thought and purity of consideration develop into tougher and extra ambiguous when the article of consideration is one thing ethical. With an eye fixed to Plato and his conception of magnificence because the seen dimension of goodness, which is inherently invisible, she writes:

It’s right here that it appears to me to be vital to retain the thought of Good as a central level of reflection, and right here too we may even see the importance of its indefinable and non-representable character. Good, not will, is transcendent. Will is the pure vitality of the psyche which is usually employable for a worthy goal. Good is the main target of consideration when an intent to be virtuous co-exists (as maybe it virtually all the time does) with some unclarity of imaginative and prescient.

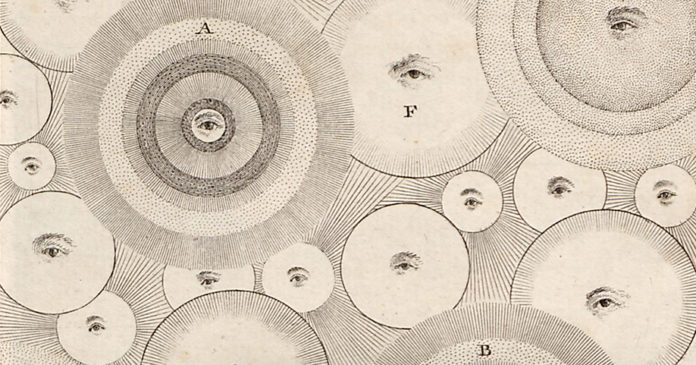

She invokes Plato’s well-known allegory of the cave — humanity’s first nice thought experiment in regards to the nature of consciousness and its blind spots, wherein the prisoners of unreality mistake the flickering shadows forged by the fireplace on the cave wall for the sunshine of actuality; however then, as soon as let out by goodness and information (and right here is one other beautiful formulation of Murdoch’s) “the ethical pilgrim emerges from the cave and begins to see the actual world within the gentle of the solar, and final of all is in a position to have a look at the solar itself.”

Shining the sunbeam of her personal mind on Plato’s blind spot to disclose the deepest which means of morality, she writes:

Plato pictured the great man as finally ready to have a look at the solar. I’ve by no means been positive what to make of this a part of the parable. Whereas it appears correct to characterize the Good as a centre or focus of consideration, but it can’t fairly be regarded as a “seen” one in that it can’t be skilled or represented or outlined. We will definitely know roughly the place the solar is; it’s not really easy to think about what it might be like to have a look at it. Maybe certainly solely the great man is aware of what that is like; or maybe to have a look at the solar is to be gloriously dazzled and to see nothing. What does appear to make good sense within the Platonic delusion is the thought of the Good because the supply of sunshine which reveals to us all issues as they are surely. All simply imaginative and prescient, even within the strictest issues of the mind, and a fortiori when struggling or wickedness must be perceived, is an ethical matter.

In consonance together with her well-known assertion that “love is the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real” — a realization that’s each the idea of morality and the driving force of science — she provides:

The identical virtues, in the long run the identical advantage (love), are required all through, and fantasy (self) can forestall us from seeing a blade of grass simply as it could actually forestall us from seeing one other individual. An growing consciousness of “items” and the try (often solely partially profitable) to take care of them purely, with out self, brings with it an growing consciousness of the unity and interdependence of the ethical world. One-seeking intelligence is the picture of ‘religion’. Think about what it’s like to extend one’s understanding of an excellent murals.

Complement these fragments from the wholly indispensable Existentialists and Mystics — which additionally gave us Murdoch on what love really means, art as a force of resistance, and the key to great storytelling — with thinker Martha Nussbaum (who, is in some ways, Murdoch’s mental inheritor) on what it means to be a good human being and physicist Alan Lightman on our search for the meaning beyond reality’s truths.