“What exists, exists in order that it may be misplaced and change into treasured,” Lisel Mueller wrote in her brief, beautiful poem about what gives meaning to our mortal lives.

To change into treasured — that’s the work of affection, the duty of affection, the nice reward of affection. The recompense of loss of life. The human miracle that makes the transience of life not solely bearable however stunning.

It’s heartbreaking sufficient that we do lose the whole lot that exists, everything and everyone we love, till we lose life itself — for we’re a operate of a universe during which it cannot be otherwise. However it’s our singular human-made heartbreak that we regularly deal with our terror of loss — that deepest consciousness of our personal mortality — by shedding sight of simply how treasured we’re to one another, squandering in less-than-love the chance-miracle of our time alive collectively, solely to get better our imaginative and prescient when entropy has taken its toll, when it’s too late. We write poems and pop songs about our self-made tragedy — “The art of losing isn’t hard to master“; “Don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.” — and we go on dwelling it.

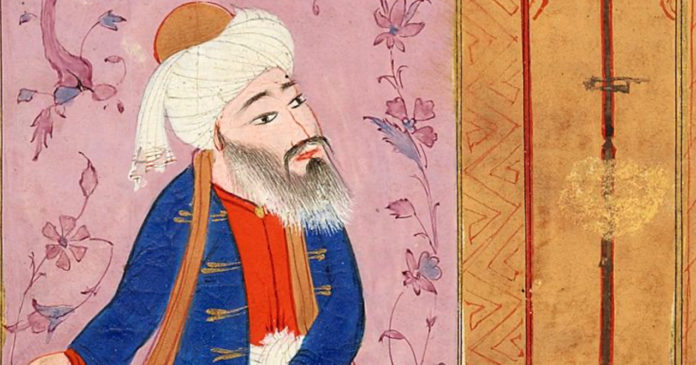

Eight centuries earlier than Mueller lived and died, an impassioned invitation to transcend our self-made tragedy took form in one other brief, beautiful poem by one other poet of unusual contact with the deepest strata of life-truth: Rumi (September 30, 1207–December 17, 1273), who believed that you should “gamble the whole lot for love, if you’re a real human being.” Rumi, historical and everlasting. Magnetic in his eloquent devotion and his soulful intelligence. Majestic in his whirling silk gown and his defiant disdain for his tradition’s worship of standing. Volcanic with poetry.

In his sixty-six years, Rumi composed almost sixty-six thousand verses, animated by an ecstatic devotion to dwelling extra totally and loving extra deeply. Having mastered the mathematical musicality of the quatrain, he grew to become a virtuoso of the ghazal with its sequence of couplets, every invoking a distinct poetic picture, every topped with the identical chorus — a type of kinetic sculpture of shock, rapturous with rhythm.

A blinding choice of his poetry, together with some by no means beforehand alive in English, seems in Gold (public library), newly translated and inspirited by poet and musician Haleh Liza Gafori.

Reflecting on the artistic problem of invoking the poetic fact of 1 epoch and tradition into one other, she writes:

The languages of Farsi and English possess fairly totally different poetic sources and habits. In English, it’s unimaginable to breed the wealthy interaction of sound and rhyme (inside in addition to terminal) and the wordplay that characterize and even drive Rumi’s poems. In the meantime, the tropes, abstractions, and hyperbole which might be so considerable in Persian poetry distinction with the spareness and concreteness attribute of poetry in English, particularly within the trendy custom. I’ve sought to honor the calls for of latest American poetry and conjure its music whereas, I hope, carrying over the whirling motion and leaping development of thought and imagery in Rumi’s poetry… I’ve chosen poems that appear to me stunning, significant, and central to Rumi’s imaginative and prescient, poems that I felt I may efficiently translate and that talk to our instances.

What emerges is a testomony to the Nobel-winning Polish poet Wisława Szymborska’s pretty notion of “that rare miracle when a translation stops being a translation and becomes… a second original.”

Right here is Haleh Liza Gafori studying for us her translation of Rumi’s lens-clearing invitation to step past our self-made tragedy and into the deepest, maybe the one, fact of life:

LET’S LOVE EACH OTHER

by Rumi (translated by Haleh Liza Gafori)Let’s love one another,

let’s cherish one another, my pal,

earlier than we lose one another.You’ll lengthy for me after I’m gone.

You’ll make a truce with me.

So why put me on trial whereas I’m alive?Why adore the lifeless however battle the dwelling?

You’ll kiss the gravestone of my grave.

Look, I’m mendacity right here nonetheless as a corpse,

lifeless as a stone. Kiss my face as a substitute!

Complement this fragment of Gold with James Baldwin on how separation illuminates the power of love and Thich Nhat Hanh on the art of deep listening — a observe additionally central to Rumi’s life — as the basis of loving relationship, then revisit poet Jane Hirshfield’s timeless hymn to love and loss.