REVIEW ESSAY

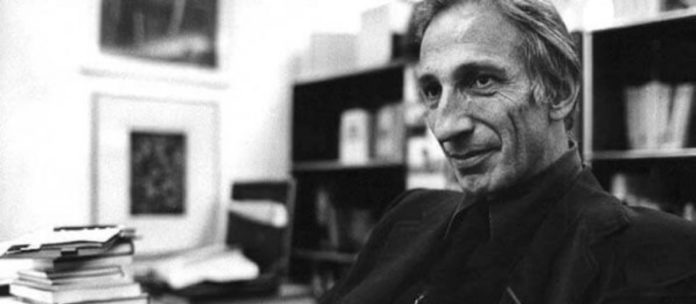

Ivan Illich: An Mental Journey

by David Cayley

Pennsylvania State College Press, 2021, 722 pages

In the autumn of 1982, the Austrian-born mental and Catholic priest Ivan Illich was invited to ship the Regents Lectures on the University of California, Berkeley. This prestigious engagement appeared just like the end result of a longtime outsider’s acceptance by the mainstream academy. As issues turned out, although, it introduced that tentative dalliance to an finish. The topic Illich selected for his lectures was controversial then, and stays so now: “gender.” His viewers included college members from Berkeley’s outstanding Girls’s Research program—a subject Illich hoped to have interaction in productive dialogue. However his hopes on this entrance had been upset. The fallout from the lectures amongst tutorial feminists resembled what we now name a cancellation.

Over the twenty years previous to this occasion, Illich had been broadly aligned with the New Left, and his arrival at Berkeley, one of many epicenters of that motion, might need been an ideological homecoming. However as controversy swirled across the Berkeley lectures, and the e-book he wrote primarily based on them, Gender, former allies denounced Illich as a reactionary. As David Cayley recounts in his new biography, at this level Illich’s “popularity on the political left suffered, and his viewers there principally fell away.” Then as now, gender and intercourse had been an ideological hazard zone. However Illich had by no means shied away from this kind of bother. In truth, fourteen years earlier than the Berkeley fracas, he had been subjected to a far older manifestation of “cancel tradition”: the Inquisition.

Illich’s lectures infuriated erstwhile allies on the Left as a result of, whereas he reiterated feminists’ prognosis of the persistence of sexism in formally egalitarian societies, his conclusions had been at odds with their sensible goals. “The pursuit of a non-sexist ‘economic system,’” as he put it, “is as absurd as a sexist one is abhorrent.” Illich was referred to as a scathing critic of progress, and maybe his mordant tackle feminist reforms mustn’t have been stunning. The books he wrote previous to Gender had superior acerbic assaults on different enterprises usually thought to be progressive, akin to schooling and financial improvement. However none had generated a backlash this extreme, which anticipated the excommunication that has these days confronted critics of the get together line on gender.

Though the bigger thrust of Illich’s pondering had remained the identical, the controversy was a serious inflection level in its public reception. His critiques of progress from the Seventies remained influential in some circles, however Gender and the work he produced after it, although in some methods richer and extra systematic than something he had written beforehand, discovered far fewer readers, and by no means gained comparable traction. Thus, by 2017, the critic George Scialabba, in an in any other case perceptive reconsideration of Illich, treats Gender briefly and his later work under no circumstances.

By the point Illich died in 2002, many obituaries offered him as a relic of the late twentieth-century counterculture, consigned to oblivion like different gurus of the period, akin to his longtime buddy Paul Goodman. However a gradual recuperation of his enduring interventions in numerous debates and fields appears to be underway. The Italian thinker Giorgio Agamben—himself lately canceled by the Left for his criticism of pandemic insurance policies—argued in his preface to a brand new Italian version of Gender that Illich’s long-neglected work could now be reaching its “hour of legibility.”

If that’s the case, David Cayley’s Ivan Illich: An Mental Journey is a vital contribution to Illich’s rediscovery. Cayley, a former producer of the Canadian Broadcasting Company’s Concepts, is well-positioned to information us via Illich’s work. He made two radio interview sequence that includes Illich, and the 2 males had been personally shut throughout the closing many years of Illich’s life. Cayley beforehand compiled The Rivers North of the Future: The Testomony of Ivan Illich, a transcript of conversations with Illich in his later years, by which he outlines a set of sweeping historic theses concerning the pervasive affect of Christianity on the secular establishments of the West.

Over the previous two centuries, most critiques of modernity have fallen into certainly one of two camps. The primary tends to see the trendy age because the spawn of the tragic dissolution of Christian civilization, which had supplied steady that means and order for over a millennium, whereas the second emphasizes the failures of modernity to meet its liberatory beliefs. In his mature thought, Illich articulated a substitute for each views, summed up within the phrase corruptio optimi pessima (“the corruption of the most effective is the worst”). For Illich, secular modernity shouldn’t be a departure from Christianity, however an extension of profound transformations set in movement by the Church.

The issue Illich diagnoses shouldn’t be that the trendy world has deserted Christianity, however that institutionalized Christianity, within the centuries after Christ, initiated destabilizing tendencies that may be radicalized within the trendy world. The Christian message, as he noticed it, was certainly one of freedom from kinship and ethnic localism that made attainable a brand new type of human neighborhood. The “new dimension of affection” introduced to the world by Christ, Illich believed, had rendered “neighborhood boundaries . . . permeable and subsequently susceptible.” The consequence was a “temptation to attempt to handle and, ultimately, legislate this new love, to create an establishment that may assure it. . . . This energy is claimed first by the Church and later by the numerous secular establishments stamped from its mildew.” Training, medication, and NGOs selling improvement, he argued, are all of the Church’s unrecognized offspring.

As a result of the affect of those establishments has unfold worldwide, Illich instructed Cayley, we dwell not in a “post-Christian period” however in, “paradoxically, essentially the most clearly Christian epoch” regardless of the waning affect of the Church itself. It follows, Cayley writes, that “the gateway to the longer term could lie up to now, buried underneath the layers of unexamined spiritual ideology that secretly gasoline our limitless pursuit of well being, schooling, security, and numerous different phantoms.” By synthesizing the insights of Illich’s multifaceted writings, Cayley’s biography permits us to move via this gateway. However what kind of future it would lead us to appears extra questionable than ever.

A Prince of the Church in Exile

Ivan Illich was born within the cosmopolitan, polyglot milieu of 1926 Vienna to a Croatian father and a German-Jewish mom who had transformed to Catholicism. He spent his early years between there and his father’s native Dalmatian coast. The distinction between the 2 locations left a finaling impression. In his father’s ancestral residence on the island of Brač, he lived in a haven of preserved premodern life that may deeply inform his sensibility. There, he remarked in a 1982 lecture, “historical past nonetheless flowed slowly, imperceptibly” and day by day life “had altered little in 500 years.”

In 1942, his mom relocated him and his brothers to Florence to flee Nazi persecution on account of their “non-Aryan” ancestry. He later returned to Austria to finish a PhD in medieval historical past on the College of Salzburg, however for the remainder of his life he would think about himself in everlasting exile. “Since I left the outdated home on the island in Dalmatia,” he instructed Cayley, “I’ve by no means had a spot which I known as my residence.” For the primary few many years of his grownup life, his solely residence can be a non secular and institutional one: the Catholic Church, into which he was ordained as a priest in Rome in 1951. And but, this was all the time a sophisticated sense of belonging, and his conflicted relationship with the Vatican would in some ways outline his whole profession.

Along with finding out for the priesthood, Illich accomplished a level on the Gregorian College in Rome, specializing in ecclesiology, or the research of liturgical ritual and the institutional constructions of the Church. He later described this subject because the research of “a social phenomenon which isn’t the state, nor the legislation,” and on this sense, “the predecessor of sociology however with a convention about twenty occasions so long as sociology since Durkheim.” His immersion on this subject decisively formed his later mental initiatives. Many twentieth-century thinkers noticed themselves as successors of the Enlightenment and its progeny: Darwin, Marx, and Freud. Illich, though in dialogue with trendy thought, all the time rooted his pondering within the older mental traditions of Christianity.

Cayley notes that in his Roman interval, “Illich’s apparent talents and his fairly conventional piety marked him out as a possible ‘prince of the Church.’” However as an alternative of pursuing the alternatives open to him in Rome, he crossed the Atlantic and took up a humble place as a parish priest in New York Metropolis, within the neighborhood of Washington Heights. Right here, he turned an influential determine in church debates about how to answer an enormous inflow of Puerto Ricans into town, which was tipping the steadiness of parishes away from earlier generations of European migrants, by now partly assimilated into American tradition, and towards a bunch who introduced with them centuries-old spiritual traditions of their very own in addition to a robust communal spirit.

For Illich, this demographic transformation was a possibility for Catholics to revisit the query of “the connection between the Gospel and its various cultural containers.” From the start, as his earlier research within the historical past of the church taught him, Christianity had vacillated between two paths in its missionary growth into cultures the place it was an alien presence: adapting to native cultures versus remaking them in its picture. As Illich noticed it, a extra versatile localism within the early Church had been succeeded, beginning within the late Center Ages, by a centralizing, homogenizing agenda. Throughout his time in New York, Illich turned a forceful advocate for the older method, advocating that the American and Puerto Rican Catholics ought to “perceive one another in a method that may enlarge the horizons of each communities.”

Regardless of Illich’s controversial positions, he discovered a lot of highly effective supporters in New York’s Catholic hierarchy, notably the conservative Archbishop Francis Spellman. Ultimately, Spellman helped him safe an appointment as Vice Rector of the Catholic College of Ponce, Puerto Rico. He didn’t final lengthy there, however the expertise would furnish the subject material of his earliest public writing in two methods. First, it made him suspicious of the modernizing improvement promoted overseas by america, and demanding of the Church’s position in such initiatives. Second, it supplied a vantage level from which to think about the important thing position of schooling in modernization.

Illich’s Puerto Rican sojourn additionally led to the creation of an establishment, the Middle for Intercultural Communication, which he later reestablished in Cuernavaca, Mexico. There, Illich’s Middle, renamed the Middle for Intercultural Documentation (cidoc), continued providing language immersion, but additionally advanced into one thing way more bold. By the late Nineteen Sixties, it was a kind of unaccredited college and suppose tank that hosted many radical intellectuals of the period. Cidoc’s guests included Paulo Freire, Erich Fromm, Paul Goodman, and Susan Sontag.

It was maybe unsurprising that, on the peak of the Chilly Struggle, Illich’s fraternization with Marxists and liberation theologians attracted suspicion from higher-ups within the Church, in addition to the CIA. It was at this level that he was obliged to look earlier than the Holy Workplace in Rome—beforehand referred to as the Inquisition. Because of this conflict, he gave up energetic duties as a priest. Cidoc held on in a considerably embattled place till 1976, at which level Illich closed its doorways.

A Critic of “Progress”

By the point he left Cuernavaca, Illich had already entered the second section of his profession: that of a public mental, writing for and chatting with audiences past the Catholic fold. Within the early Seventies, as he was within the strategy of distancing himself from the ecclesiastical establishments that had circumscribed his profession as much as that time, he turned one thing of an establishment himself: certainly one of numerous itinerant radical gurus, like his associates and collaborators Paul Goodman and Erich Fromm, who had been preaching messages of particular person and social transformation.

His first e-book, Celebration of Consciousness: A Name for Institutional Revolution is a set of manifestos and polemics that mix a New Left–type assault on the “dehumanization” led to by superior technological civilization with an account of the Church’s complicity in these tendencies and a requirement for “radical humanism” that charts a brand new path. In keeping with Cayley, Illich noticed within the Nineteen Sixties “a second of what Christian custom has known as kairos”—that’s, “a propitious second for choice and motion.” He believed “modernity [was] reaching a most at which it may and have to be reworked.” At such a second, in Cayley’s phrasing, “nice promise and nice hazard sit aspect by aspect.” However the sense of promise, for a time, outweighed the sense of hazard in Illich’s pondering. Therefore, his second and third books, Deschooling Society and Instruments for Conviviality, had been animated by a sensible imaginative and prescient of reform that emphasised the potential for reconfiguring technological modernity inside viable limits.

Deschooling Society was, in Cayley’s phrases, “a right away trigger célèbre” and “essentially the most broadly mentioned and debated of all of Illich’s writings.” The challenge had its beginnings in Puerto Rico, the place Illich had initially advocated without spending a dime main education for the poor. However as he started to review the observable results of the growth of education, he observed its perverse penalties. The results of obligatory mass education, a comparatively new presence in rural Puerto Rico, was not a “stage enjoying subject” between wealthy and poor, however an inclination to “compound the native poverty of half the youngsters with a brand new sense of guilt for not having made it.”

College, Illich got here to see, might have the impact of justifying social inequality fairly than redressing it. These higher outfitted to leap via the academic system’s hoops, often by advantage of getting households that had ready them, had been rewarded as if their tutorial success was a manifestation of particular person advantage, whereas those that couldn’t obtained the message that their failings had been all their very own. Simply as dangerous, he argued, was the college system’s synthetic monopolization of studying. The ideology of schooling tacitly declared that information, which could underneath different circumstances be acquired via unbiased research, apprenticeship, and different means, was a scarce commodity solely obtainable by passing via prescribed rituals.

Illich’s background in ecclesiology and church historical past knowledgeable these traces of criticism. The Gospel message, as he noticed it, was a present of unconditional, limitless love and fellowship. But the historical past of the Catholic Church was that of the institutionalization of this subversive message. The voluntary fellowship of early Christians, which transcended the normal boundaries of household and ethnic belonging, advanced into the obligatory rituals imposed by the Church on the peak of its energy. Likewise, studying at its greatest was a spontaneous train of curiosity in freely chosen collaboration with others, and college was a perversion of this risk. Therefore, he argued, faculty needs to be “disestablished,” because the Church had been in most Western nations.

Illich’s optimism concerning the disestablishment of faculty proved unfounded. If something, the salvific imaginative and prescient of schooling later got here to animate policymakers greater than ever earlier than. In america, because the welfare state was scaled again throughout the Eighties and Nineteen Nineties, schooling was promoted because the “nice equalizer” that may allow these in poverty to boost their way of life via their very own efforts, versus falling into dependency on the state. This missionary endeavor culminated within the bipartisan No Youngster Left Behind Act and its Obama-era successors. As Illich would have predicted, the ensuing bureaucratization of studying right into a regime of testing and analysis left many children behind, as inequality continued to skyrocket. However since virtually nobody questioned the assumptions behind these insurance policies, the answer was all the time extra faculty.

Paradoxical Counterproductivity

Illich’s examination of education helped lead him to a broader thesis he known as “paradoxical counterproductivity.” This was a dynamic that took maintain “each time using an establishment paradoxically takes away from society these issues the establishment was designed to supply.” It isn’t merely that faculty fails to impart information; it additionally degrades and corrupts information by enclosing it inside the system of self-perpetuating rituals and perverse incentives different social critics have designated “credentialism.” Anybody who has taught will probably be aware of the kind of pupil who hasn’t the slightest curiosity in the subject material however an intense concern with easy methods to get an A. No matter their different faults, such college students are continuing from a sensible view of the establishment they’re working inside, which has changed studying with synthetic indicators of it.

In his subsequent writings from the Seventies, Illich tracked the consequences of paradoxical counterproductivity throughout different domains of contemporary life. Turning to a realm seemingly distant from education, he took on one other mainstay of modernization initiatives being promoted throughout the growing world: transportation infrastructure. In Power and Fairness, written throughout the 1973 oil disaster, he outlined the ways in which trendy applied sciences of mobility had promised autonomy and freedom however actually disadvantaged individuals of each. His darkly humorous account of the perverse results of the car in that e-book encapsulates a lot of his bigger critique of progress. He calculates that, when you embrace the additional labor required to pay for a automotive, its repairs, gasoline, taxes, and so forth, “[t]he mannequin American places in 1600 hours to get 7500 miles: lower than 5 miles per hour. In international locations disadvantaged of a transportation trade, individuals handle to do the identical.”

The varsity dropout and the commuter caught in interminable site visitors, according to Illich, are usually not unintentional byproducts of insufficiently advanced techniques that may be reformed in the direction of larger effectivity. They’re the required consequence of the paradoxical counterproductivity that afflicts all initiatives motivated by the trendy dream of limitless progress. Maybe his most controversial utility of this perception was to the sphere of drugs within the e-book Medical Nemesis, later reissued as Limits to Medication. His topic on this e-book, the longest of what he known as his “pamphlets” of the Seventies, is iatrogenesis, a time period sometimes utilized in relation to unintentional physician-caused harms inflicted in the middle of remedy. As Cayley explains, Illich “applies it way more broadly to absorb all of the methods medication reshapes the society it ostensibly serves.”

Medication, in Illich’s account, does for well being what schooling does for studying: it converts a very good that folks would possibly autonomously domesticate right into a scarce commodity solely accessible via an establishment that monopolizes its distribution. The current pandemic has supplied numerous illustrations of this phenomenon. For example, it was clear from the earliest statistical measures that SARS-CoV-19 affected totally different demographics in another way: extreme illness was closely concentrated among the many outdated and sick. It adopted that for broad swathes of society, “well being” would possibly effectively be obtained by experiencing a light an infection and gaining pure immunity to the virus. But a barrage of propaganda has obscured these variations, all the time in service of the notion that well being might solely be obtained by medical intervention: first through the advert hoc “non-pharmaceutical interventions” rolled out in 2020, later by vaccination. To confess that unvaccinated younger individuals, notably these in good bodily form, are at decrease threat from Covid-19 than vaccinated older individuals can be heresy, because it implies that salvation is feasible exterior the church.

Illich additionally took purpose at one other assumption these days on show: as Cayley places it, “the concept that struggling and demise are unqualified evils and their postponement unqualified items.” Up to now two years, politicians and public well being officers have proceeded from the view that an indefinite suspension of the optimistic items of civic and familial life is legitimated by the crucial of “saving lives.” As Illich’s counterproductivity thesis anticipates, the result’s a stripping down of the lives which can be declared in want of saving to what Giorgio Agamben calls “naked life.” The reception of Illich’s e-book anticipated that of Agamben’s criticisms of the “techno-medical despotism” of pandemic emergency rule: he was accused of callous indifference to human life. However even larger controversy would envelop Illich within the subsequent section of his mental profession.

The Richness of Subsistence

All through his polemical pamphleteering of the Seventies, Illich had inveighed towards what he known as the “conflict on subsistence.” By this latter time period, Cayley clarifies, Illich didn’t merely imply “the naked minimal for survival,” however “what’s produced for its use worth fairly than its change worth” (in Marxian terminology): that’s, “what makes its contribution to livelihood fairly than to GNP.” In domains starting from faculty to medication to transportation, as we’ve got seen, Illich noticed that “industrial manufacturing . . . workouts an unique management over the satisfaction of a urgent want, and excludes nonindustrial actions from competitors.” He noticed the so-called growing world, the place the subsistence mode remained widespread, because the central enviornment for reasserting use worth and halting the unfold of the “radical monopoly” of execs.

In his later writing from this era, Illich started to confer with the realm he had beforehand known as “subsistence”—that of “autonomous, non-market associated actions via which individuals fulfill on a regular basis wants”—as “the vernacular.” Cayley explains that “Illich’s effort to mark out a vernacular sphere was meant to stop the conflation of genuinely autonomous exercise with what he known as ‘shadow work.’” The latter phrase turned the title of a 1981 e-book by which Illich examined “the unpaid work which an industrial society calls for as a obligatory complement to the manufacturing of products and companies.” He was already attuned to this phenomenon in earlier books like Power and Fairness, the place he documented the explosion of unremunerated hours spent by commuters idling and performing repairs. In Shadow Work, he outlined this and comparable exercise as a type of unrecognized labor that had proliferated in industrial societies.

Illich’s examination of shadow work was what led him to take an curiosity in feminist scholarship. His theorization of the uncompensated work that sustained the cash economic system overlapped with feminist theorizations of housekeeping and located an echo within the ideas of the “Wages for Housework” marketing campaign spearheaded by radical activists akin to Silvia Federici within the mid-Seventies. They regarded the “caring work” or “reproductive labor” principally assigned to ladies because the unacknowledged linchpin of capitalist manufacturing. The purpose of demanding compensation was to disclose that the financial system was depending on labor not acknowledged as such.

Shadow work, as Illich outlined it, is throughout us immediately. When he was writing on the topic, pumping your individual gasoline was a current innovation, and most might see that it entailed the alternative of a activity that had corresponded with wage labor with an unremunerated activity on the a part of the buyer. Now it’s so acquainted as to go unquestioned. Supermarkets and different shops have adopted swimsuit with self-checkout kiosks, the place the buyer takes on the job as soon as carried out by a cashier. Data know-how has expanded shadow work into areas Illich couldn’t anticipate. For example, the notion of “playbor,” first used within the digital video games trade to confer with the uncompensated work of gamers in bettering video games, has come to confer with the free “work” web customers carry out on platforms that revenue from their clicks and eyeballs. Commenting on this phenomenon, in 2014 the artist Laurel Ptak issued a semi-satirical manifesto known as “Wages for Facebook,” an invocation of the sooner feminist motion.

For Illich, the shadow work phenomenon was half and parcel of the substitute dispensation he known as “shortage.” Important human items, he argued, had as soon as belonged to the commons, however had been subordinated to financial imperatives, to the extent that the mundane actions of day by day life had been not that: they’d come to ivolve incessant manufacturing and consumption. Well being, as soon as one thing people and communities might domesticate, had develop into a commodity distributed by medical suppliers, simply as information had been changed with the credentialist pursuit of institutionally sanctioned status in class. By means of the notion of shadow work, Illich got here to see that mundane day by day actions and fundamental types of sociability had been absorbed into commodity manufacturing—and he didn’t even dwell to see social media and relationship apps.

Intercourse, Gender, and Capitalism

By the early Eighties, Illich had relinquished the optimism about achievin a position reforms that had animated his earlier work, and turned away from pamphleteering towards extra scholarly initiatives. He envisioned writing a “historical past of shortage” that may hint the tendencies towards the enclosure and commodification of products throughout the longue durée of Western historical past. His appreciative engagement with scholarship within the burgeoning fields of girls’s research and ladies’s historical past led him to the idea of “gender,” which he got here to see as a pivotal lens for understanding processes that had lengthy preoccupied him: the usurpation of the commons by establishments {and professional} consultants, and the substitution of use worth with change worth.

Within the years earlier than Illich took up the topic, “gender,” beforehand utilized in grammatical contexts, had come to indicate traits hooked up to the sexes particularly sociocultural settings. The terminological distinction between gender and intercourse performed a key position in feminist efforts to denaturalize expectations and stereotypes round ladies. Because the vanguard of gender pondering has shifted its consideration to transgender causes in recent times, many activists have gone additional than they did in Illich’s time, arguing that, sex, too, is a social, cultural, and linguistic assemble. In response, their critics assert the existence of an immutable underlying duality of women and men detached to tradition and language: most sometimes, “organic intercourse.”

Gender, the e-book Illich developed out of his fateful 1982 Berkeley lectures, can be prone to ruffle feathers on either side of this debate immediately—if anybody learn it. To an extent, Illich concurs with immediately’s gender radicals: he not solely accepts that gender is socially constructed, but additionally makes the case that “organic intercourse” shouldn’t be a mere impartial truth, however a uniquely trendy method of framing the variations between women and men. “Intercourse,” he claims, steadily supplanted the array of culturally particular iterations of the gender divide that prevailed in premodern societies.

His time period for the latter, the identical he utilized in his different writing on domains of subsistence, is “vernacular gender.” His use of the phrase hints at why makes an attempt to change language have loomed so massive within the gender debate. Whereas in an earlier period feminists fought for inclusive language, immediately’s vanguard of activists goals to decouple gendered language from biology altogether—for instance, by changing “pregnant ladies” with “pregnant people.” Such language reforms appear invariably to neuter the vernacular of gendered distinction. Illich’s account means that this course of displays the hollowing out of “vernacular gender” by the trendy notion of intercourse.

Vernacular languages possess distinct grammatical classes and syntactical guidelines—however all possess some such classes and guidelines. Analogously, for Illich, “vernacular gender” partitioned societies into distinct spheres of exercise related to women and men. What these spheres consisted of differed dramatically from tradition to tradition, however what didn’t differ previous to the rise of business capitalism was the structuring position of vernacular gender in figuring out what bodily areas women and men occupied, what duties they carried out, and what instruments they used.

Illich, then, shares the now standard view that the “gender binary” is fully socially constructed, culturally particular, and malleable, however he additionally argued that some model of this fundamental construction, no matter its particular content material, was ubiquitous in premodern societies. However opposite to the widespread notion that this “binary” stays a predominant mode of oppression, Illich claims that this polarity has been attenuated within the trendy period by the alternative of vernacular gender with intercourse—a course of that he argues was initially financial in nature.

Vernacular gender circumscribes actions, such that “[o]utside industrial societies, unisex work is the uncommon exception. Few issues might be completed by ladies and likewise by males.” Whereas “[g]ender is substantive,” Illich asserts, “intercourse is a secondary attribute, a property of a person.” The weakening of the vernacular regime of gender-specific areas, actions, and instruments enabled trendy societies to recast women and men as performers of summary labor in change for wages. Industrial capitalism, he argues, thus replaces gendered people, whose lives play out within the distinct gendered spheres of their specific tradition, with a unisex homo economicus.

Because of this, for Illich, “[t]he lack of vernacular gender is the decisive situation for the rise of capitalism.” The sorts of work open to both intercourse would possibly differ by time and place and would possibly seem stratified alongside comparable traces to gendered work. The distinction is that every one work is now carried out in relation to the money nexus, which assigns worth to labor by way of the common equal of cash. The fashionable very best of equality between the sexes, for Illich, derives from and is outlined by way of the financial abstraction of labor as a commodity bought in the marketplace. Previous to this, it was unattainable to conceive of labor on this method, as a result of all work occurred solely in gendered spheres of exercise. Since males’s and ladies’s work was not equal or transferable, there may very well be no basic class of “work” that may very well be assigned summary financial worth.

Illich’s feminist critics regarded Gender as a nostalgic paean to the fastened gender roles of the previous, and his personal phrasings generally encourage that impression. Illich’s express purpose, nonetheless, was to account for the trendy failure to attain financial parity between women and men. “I do know of no industrial society the place ladies are the economic equals of males,” he writes. “Of every little thing that economics measures, ladies get much less.” It is because ladies are “disadvantaged of equal entry to wage labor solely to be sure with even larger inequality to work that didn’t exist earlier than wage labor got here into being.” The reference right here is, once more, to the kinds of shadow work or reproductive labor that fall disproportionately to ladies, which, in his evaluation, differ from ladies’s work underneath vernacular gender on account of their devaluation by the labor market.

Those that accused Illich of reactionary nostalgia tended not to answer his most difficult allegation: that, insofar as they’re blind to the basis causes of contemporary financial degradation within the suppression of vernacular gender, radicals who demand parity between the sexes (or extra lately, the genders) are tacitly endorsing a mannequin of equality grounded within the formal common equivalence of cash; consequently, their proposed reforms can solely serve to broaden the attain of the money nexus. Simply as some feminist visions of equality could reinforce and supply a brand new foundation for the exploitative mannequin of a unisex homo economicus competing to promote labor, the present notion of “gender identification” as a self-designated, interchangeable attribute turns it into one other free-floating commodity to be acquired and discarded like several shopper good.

The implication right here is that the modern opposition between “gender identification” and “organic intercourse” is illusory. For Illich, the invention of intercourse follows the evacuation of the substantive lifeways of vernacular gender and the imposition of summary equivalence. Therefore the discount of variations between women and men to intercourse, by disembedding distinction from concrete regimes of gender, makes attainable the proliferation of summary, commodified gender.

However Illich offers no sense of how this course of is likely to be reversible. He acknowledges on the finish of Gender: “I’ve no technique to supply. I refuse to take a position on the possibilities of any remedy.” Right this moment, his conclusions are prone to be as unpalatable to those that want to reassert the truth of organic intercourse as to those that demand the authorized recognition of self-proclaimed gender identification.

Cyberculture and Self-Algorithmization

For Illich, the “lack of gender” was a fait accompli. In contrast, one other main preoccupation of his later profession was with a historic improvement he believed was nonetheless underway: the emergence of the “age of techniques.” In his earlier writing, Illich had approached technological instruments as Marshall McLuhan had: as “extensions of man.” The “age of instrumentality,” he argued, had begun not with Gutenberg however with medieval developments within the historical past of the e-book that had made written texts extra legible and accessible, and thereby enabled the growth of lay literacy. The e-book had reworked human subjectivity within the subsequent centuries. The rise of computer systems and community know-how, he believed, was bringing a couple of comparably radical shift.

In his earlier work, Illich had expressed some enthusiasm for the probabilities of networked computer systems. For instance, in Deschooling Society, he imagined that “studying webs” of long-distance collaborators would possibly allow the pursuit of information to take new varieties, exterior of institutional constructions. Because of this enthusiasm, he exerted a sure diploma of affect on the transition from “counterculture to cyberculture,” as described by Fred Turner in his book of that title. For example, Lee Felsenstein, a founding member of the influential Homebrew Laptop Membership who helped pioneer the private laptop, was an outspoken admirer of Illich.

However by the Eighties, as the private laptop was turning into ubiquitous, Illich turned involved with its disembodying, depersonalizing results. As Cayley places it, he believed that integration with computer systems risked turning a “distinctive, enfleshed, and irreducible particular person” into “an merchandise of knowledge, a sample of dangers.” The sooner “age of instrumentality,” the consequences of which he had additionally assessed critically, “was characterised by the elemental distinction . . . between the instrument and its person,” which stay basically separate regardless of how built-in. Conversely, a system (like networked computer systems) “incorporates me once I enter it—I develop into a part of that system and alter its state.”

Illich was particularly involved with the rising centrality of threat consciousness made attainable by the rise of ever extra subtle applied sciences of calculation, monitoring, and prediction. The “ideology of threat consciousness,” he argued, had a disembodying impact: “[i]t is a inserting of myself, every time I consider threat, right into a base inhabitants from which sure occasions . . . might be calculated. It’s an invite to intensive self-algorithmization.” He made this assertion twenty years earlier than both DNA checks claiming to foretell the likelihoods of assorted problems or wearable digital units monitoring very important indicators had been commercially out there. Right this moment, the kinds of procedures Illich cautioned towards are so built-in into our lives that we barely discover their operation.

Like his modern Jean Baudrillard, Illich glimpsed the emergence of a world in which—in Cayley’s phrases—“[m]odel and actuality merge, the distinction undetectable, because the mannequin grows ever extra responsive and ever extra attuned, techniques develop ever extra clever, and algorithms persuasively simulate ever extra of our habits.” It’s little marvel that, given the totalizing energy of the “age of techniques” he confronted in his later years, Illich’s pondering turned apocalyptic. The reformist optimism of his earlier works gave option to a way {that a} huge “equipment for suppressing and stopping shock” was turning into ineluctable.

Illich’s concern with the suppression of shock by chance calculation was of a bit together with his broader critique of the institutionalization of Christian vocation. “Our hope of salvation,” he wrote in his first e-book, “lies in our being stunned by the Different.” He noticed the visitation of Mary and the incarnation of Christ because the paradigmatic illustrations of this shock, together with the parable of the Good Samaritan. As Cayley explains, “Illich claimed this parable had been persistently misunderstood as a narrative about how one ought to behave.” In his studying, the significance of the Samaritan’s act is that he “loves exterior the classes that prescribe his allegiance and obligation” and “stands for this freedom to invent, to reply, to take unpredictable instructions.”

Within the late work he undertook in dialogue with Cayley, Illich tried to hint the “roots of modernity” to “the makes an attempt of the church buildings to institutionalize, legitimize, and handle Christian vocation”—the thesis he summed up, once more, within the motto corruptio optimi pessima. He additionally described this as “the historic development by which God’s Incarnation is turned . . . inside out.” The implication of this concept is apocalyptic within the unique sense: an unveiling, “a revelation of the ‘thriller of evil,’ the thriller of what occurs when God’s final present is co-opted and put to work, made to generate guidelines, bear curiosity, and information authorities.” For the late Illich, “the top has come, if the top is taken to confer with a ‘world that has gone about so far as it may go.’”

Secularized Faith amid Secular Stagnation

Illich died twenty years in the past of a slow-growing tumor he refused to deal with—a selection constant together with his rejection of the subjugation of freedom and shock to medical threat calculation. “To hell with life!” he exclaimed in a late speech, expressing his disgust on the secular “idolization of life,” which additionally entailed the identification of demise as an exterior enemy towards which unremitting conflict have to be waged. As Cayley explains, for Illich, “life signify[ed] the transformation of one thing that one does in dwelling into one thing one has”—which turns into one thing “for which the doctor assumes accountability [and] which applied sciences extend.”

The pandemic years have uncovered us all to the political penalties of the “idolization of life” Illich warned towards. Within the Covid state of emergency, “saving lives” has supplied politicians and public well being officers carte blanche for the indefinite suspension of a lot of what offers dwelling its worth. The counterproductivity of such measures, which prohibit dwelling within the identify of preserving life, is compounded by their poor file of reaching their acknowledged goals. The self-positioning of “consultants” as custodians of life has ratified Illich’s considerations concerning the excesses of medical energy.

Illich’s writings comprise many uncanny anticipations of the current: the repeated failures of “schooling reform”; the ever-expanding ambit of threat calculation in private and political life; the transformation of gender right into a free-floating digitalized abstraction. However what he didn’t totally foresee was {that a} model of his closing apocalyptic imaginative and prescient can be embraced by the skilled lessons, whose affect he excoriated, in addition to the worldwide governing elite. In Illich’s early profession, he fought towards the ability constructions that, swelling with hubris amid the fast development of the postwar period, had charged a brand new clerisy of execs with spreading a false gospel of limitless development. Deluded by such goals of infinite growth, he contended, the world had embraced a blasphemous secular fantasy of salvation and overpassed what was basic.

Illich had good causes for concern, however we now confront a stranger panorama. Lately, essentially the most highly effective individuals on the earth have fawned over a Swedish teenager who castigated them with secular hellfireplace sermons demanding infinite sacrifice; CEOs have alternated between encomiums to renewable-energy sustainability and grim invocations of the local weather menace; and advocates of degrowth have gained outstanding positions within the media and academia. The modernist goals of improvement that distressed Illich have principally vanished from the West.

As a substitute, our ruling elites conceal their lack of any optimistic imaginative and prescient in any respect beneath shows of performative conscience-laundering. This ideological transformation is sensible as a submit facto justification of the fabric actuality of secular stagnation. For the custodians of an economic system unable to generate a lot development past the growth of speculative finance capital enabled by everlasting stimulus, the denunciation of progress has develop into strategic and rational for these in energy. In the meantime, the developmentalist initiatives Illich noticed as a Western imposition on cultures of subsistence have discovered a brand new base of operations within the East, motivated by nationalist pursuit of benefit fairly than a messianic universalism inherited from Christianity.

The resilience of the establishments Illich noticed as destined to wane now derives partially from their capability to soak up and repurpose critiques resembling his personal, as a brand new mode of paradoxical legitimation. Within the Seventies, “you’ll own nothing and you’ll be happy” might need appeared like a mantra of hope for conviviality, decommodification, and the restoration of use worth. Right this moment, it captures an solely considerably hyperbolic anxiousness about an emergent world regime of digital feudalism underwritten by secular moralism and ecological doomsaying. The reassessment of Illich’s work Cayley has made attainable additionally calls for that we grapple with this ironic legacy.

This text initially appeared in American Affairs Quantity VI, Quantity 2 (Summer time 2022): 208–24.