Content material

This content material will also be considered on the positioning it originates from.

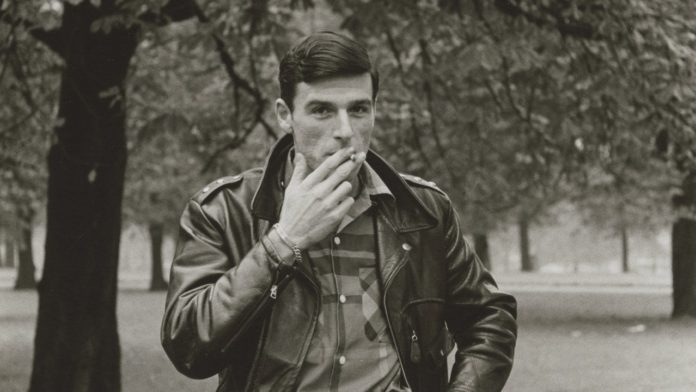

The Victorian home, within the Higher Haight neighborhood of San Francisco, the place the British-born poet Thom Gunn lived for greater than thirty years and the place he died, in 2004, on the age of seventy-four, is as fairly as all the opposite homes on Cole Road. It was bought partially with a Guggenheim grant that Gunn obtained in 1971, and he shared it along with his long-term accomplice, the theatre artist Mike Kitay, and numerous of their respective lovers and mates. In his queer house, Gunn, who’s greatest identified for his profound 1992 assortment “The Man with Evening Sweats,” a sequence of meditations on the affect of AIDS on his neighborhood, established a self-discipline of care that was a supply of stability and luxury to him throughout the seismic adjustments in homosexual life that occurred throughout his years there. “Three or 4 occasions every week somebody cooks for the entire home and visitors,” Gunn wrote to a good friend not lengthy after transferring in. “I’ve cooked for 12 a number of occasions already. . . . So issues are understanding very properly: it’s actually, I understand, the way of life I’ve needed for the final 6 years or so.”

One’s expertise of Gunn’s poetry—which is, by turns, conversational, formal, and metaphysical, and sometimes all three directly—is deeply enhanced by the life one discovers in “The Letters of Thom Gunn” (expertly co-edited by Michael Nott—who offers a heartfelt and educated introduction—and Gunn’s shut mates the poets August Kleinzahler and Clive Wilmer). Gunn’s letters are a primer not solely on literature (he taught a rigorous class at U.C. Berkeley on and off from 1958 to 1999) however on the poet himself, who had a bent to cover in plain sight. “I’m the soul of indiscretion,” he as soon as informed his good friend the editor and writer Wendy Lesser, however he had an aversion to being seen, or, extra precisely, to confessional writing that mentioned an excessive amount of too loudly. (In a 1982 poem, “Expression,” Gunn made droll sport of his exasperation: “For a number of weeks I’ve been studying / the poetry of my juniors. / Mom doesn’t perceive, / they usually hate Daddy, the famous alcoholic. / They write with black irony / of breakdown, psychological establishment, / and suicide try. . . . It is vitally poetic poetry.”)

“The deepest feeling at all times reveals itself in silence; / Not in silence, however restraint”: so wrote Marianne Moore in 1924, and people strains got here to thoughts many times as I learn Gunn’s letters, the place he reveals himself, deliberately or not, by not consistently revealing himself. “You at all times credit score me with lack of feeling as a result of I typically don’t present feeling,” he wrote to Kitay in 1963. “I’m certain that my feeling threshold can also be a lot larger than yours, but additionally I don’t notably need to present it. . . . I like the understatement of feeling greater than something.”

Born in Gravesend, Kent, in 1929, William Guinneach Gunn—he added Thomson later—was the primary youngster of Herbert and Charlotte Gunn. (A youthful brother, Ander, to whom he was shut all through his life, was born in 1932.) His mother and father, who had been each concerned with phrases, met in 1921, on the places of work of the Kent Messenger, the place they had been trainee journalists. Herbert turned the northern editor of the conservative Each day Categorical, whereas Charlotte stayed at house and took care of the kids. Gunn’s childhood, which he maintained was a really completely satisfied one, was conventional; he realized humility, gratitude, and political consciousness in equal measure. (The primary letter within the assortment, dated 1939, was written to Gunn’s father: “Thank-you for the beautiful toy theatre, we now have performed with it from early morn until sundown. . . . I am going to a backyard social gathering to assist ‘poor Spain’ on Saturday. Ander needs a pistol you shoot little movies out of, you get them from Selfridges if this isn’t too spoily.”)

In one in all his only a few autobiographical essays, “My Life As much as Now” (1979), Gunn wrote, of Charlotte:

For middle-class English girls of Charlotte’s era (she was no Bloomsbury aristocrat), calling consideration to oneself was simply not carried out. Charlotte was a voracious reader, and impressed a love of language in her elder son. “The home was filled with books,” Gunn wrote in “My Life As much as Now.” “From her I acquired the whole implicit concept, from way back to I can keep in mind, of books as not only a commentary on life however part of its persevering with exercise.” In a 1999 interview with James Campbell, Gunn recalled how when he was eleven, throughout the Blitz, residing on the boarding college Bedales, he requested his mom what he ought to give her for her birthday. “Why don’t you write me a novel?” she replied. He did, composing a chapter a day throughout the college’s afternoon siesta time.

We be taught to make artwork by refracting and rearranging what we intuit in regards to the emotional ambiance we reside in: Gunn’s novel, which concerned adultery and divorce and was titled “The Flirt,” could have been a reimagining of what he noticed at house. Between 1936, when Charlotte and Herbert separated for the primary time, and 1944, when she died by her personal hand, Charlotte had an affair with a good friend of Herbert’s, Ronald (Joe) Hyde, returned to Herbert, separated from him once more, divorced him, married Hyde, broke up with Hyde, reconciled, after which separated once more. It was in December, 4 days after Christmas, that Charlotte barricaded herself within the kitchen and put a gasoline poker in her mouth. Her sons discovered her the following morning. The morning after that, Gunn wrote this in his diary:

The picture of fifteen-year-old Gunn kissing his mom’s legs is sort of a Pietà in reverse: he’s Jesus providing Mary a caress. Grief separates the physique from itself. You could be in a room with essentially the most horrible factor you’ll expertise and never be there in any respect. Gunn’s anguish right here doesn’t detract from his photographic powers of description. His diary entry isn’t included within the “Letters”—it seems within the British version of Gunn’s “Chosen Poems”—nevertheless it ought to have been. Marvelling on the horror of this scene and Gunn’s management within the midst of it helps put together you for what comes later: all of the lifeless our bodies he describes, examines, and kisses goodbye in “The Man with Evening Sweats.”