People like to look on the intense facet. We course of our traumas and congratulate ourselves on our resilience. We prefer to crown ourselves winners, avoiding the stigma of the L-word deployed by a sure ex-president. The triumph of the therapeutic, as Philip Rieff referred to as it, even applies to our anti-free-speech school college students, who achieve vituperative power from the hurt supposedly inflicted on them by different folks’s unpleasant opinions.

However there’s a darkish flipside to the story. People can’t flip their eyes away from failure. Nobody is so attention-grabbing to us because the particular person, ideally a star, who has sunk to essentially the most degraded, soul-crushing Marianas Trench of existence, capsized, busted, shellacked, KO’d, and worn out. Some more true sense of issues appears to return with loss. The particular person wholly crushed by life is the one who is aware of the rating. In failure, actuality doesn’t evade us.

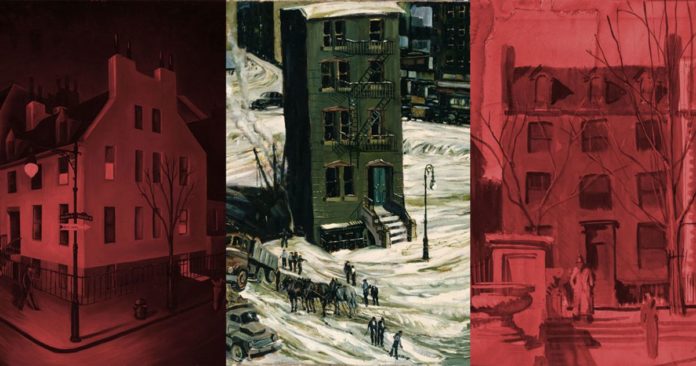

American authors of the early twentieth century speculated in failure the way in which the tycoons of their day wager on shares. Theodore Dreiser, Willa Cather, Wallace Stevens, Ernest Hemingway, T.S. Eliot, William Faulkner, Robert Frost—these writers discover illumination inside pessimism, and so they’re everlasting members of the American canon.

Twentieth-century American literature bought off the beginning block with the naturalist trio of Stephen Crane, Frank Norris, and Theodore Dreiser, who aimed a primitive sledgehammer on the notions of the progressive period. Progressives insisted that each one human issues could possibly be alleviated by way of social tinkering. Solidarity and peace would blossom, if reformers might solely give you the fitting method for a simply society.

However Dreiser and his contemporaries had a disillusioned sobriety that seemed straight on the exhausting contours of actuality: poverty, demise, illness, sexual frustration, lack of love.

When Dreiser first got here to New York in 1894, within the midst of an financial crash, he was struck by the “hugeness and pressure and heartlessness of the nice metropolis.” New York was “gross and merciless,” he famous. Dreiser slept in flophouses, a wretched loser like Hurstwood in Sister Carrie, the scandalous first novel he revealed just a few years later. Like Crane and Norris, Dreiser by no means misplaced the sense that life is ruthless.

Dreiser was a Midwestern oaf, massive and awkward, a person of blunt sexual cravings. His crowning work was the mammoth An American Tragedy, revealed in 1925, which stays essentially the most riveting 900-page guide I’ve ever learn. An American Tragedy is about Clyde Griffiths, a colorless younger man who kills his girlfriend and ultimately goes to the electrical chair. Clyde needs to be a part of the glittering society of Lycurgus, a city in upstate New York—would-be flappers and their beaus having what they describe as enjoyable. Clyde’s pregnant, working-class girlfriend, Roberta, will get in the way in which—Clyde has his eye on a glamorous younger socialite named Sondra—and so, with excellent plausibility, the considered murdering her steals on him. This part of Dreiser’s narrative crawls ahead as suspensefully as Crime and Punishment, as Clyde turns into an increasing number of used to the prospect of Roberta’s demise. Whereas they’re boating in a desolate upstate lake, Clyde strikes her, half accidentally; she falls out of the boat, and he lets her drown. The scene is an agonizing tour de pressure. David Denby writes that “Clyde’s consciousness, by no means very full to start with, and now divided between homicide and guilt, is deranged additional by the darkish great thing about the lake, the cry of unfamiliar birds, the empty woods.”

Clyde Griffiths is like all of us, Dreiser is saying. What sums him up isn’t the clumsy act of homicide however his lengthy slide towards ethical numbness, which is a sin, sure, but additionally a recognition of the information of existence.

When Dreiser footage the demise home, the ultimate station of Clyde’s tormented existence, he’s one with Clyde each harrowing step of the way in which:

The glooms—the strains—the indefinable terrors and despairs that blew like winds or breaths about this place and depressed or terrorized all by turns! They have been manifest on the most surprising moments, by curses, sighs, tears even, requires a track—for God’s sake!—or essentially the most unintended and surprising yells or groans.

For Dreiser jail is just a extra intense model of anyplace else. Dreiser, Alfred Kazin remarked, at all times had “the sense that injustice makes society potential. It was one other type of the carnage that sustains nature.” Each love affair requires that somebody has been jilted. A rich, well-dressed man has only one operate, to remind a hapless, ravenous bum like Hurstwood of the bitterness of his social humiliation.

Dreiser’s model typically feels flat-footed, even cloddish, however this isn’t the rationale that he grew to become a goal for critics like Lionel Trilling, who wished novelists to enact the free play of the thoughts. For Dreiser society was as definitive as a jail cell—there may be nothing free about it.

Willa Cather was Dreiser’s reverse quantity by way of model. The inevitability of Dreiser’s prose lies in his agitated energy to see inside his defective, stumbling protagonists, and to reflect their flaws. Cather’s model is completely distinct—the whole lot she wrote appears completely finished. She too sounds inevitable. No American author has a greater sense of the land itself, forbidding and large as it’s. Cather by no means forgot her first sight of Nebraska when she first arrived at 9 years previous, “jerked away,” as she put it, from the hills of her native Virginia and “thrown out into a rustic as naked as a chunk of sheet iron.”

This inhuman land, with its empty bleakness, was made to thwart the poor immigrants who tried to farm it. Typically they succeed, like Alexandra in O Pioneers, however usually they’re defeated.

Cather was a “sturdy, bossy girl,” Joan Acocella famous, and she or he wrote, not “fables of prairie advantage,” however “some form of unusual poetry, concerning the terror of life.” The fear exhibits up within the tragic fates of Cather’s characters: the daddy who blows his brains out with a shotgun, or the drifter who throws himself right into a threshing machine.

A quieter model of failure exists too in Cather. Godfrey St. Peter in The Professor’s Home sits alone and remembers his shining protégé Tom Outland, killed in World Battle I, an adventurer and inventor who earlier than his demise instructed Godfrey concerning the exhilarating summer time he spent within the ruins of a Native American cliff metropolis within the Southwest. Tom’s epiphany brims with gentle:

I can scarcely hope that life will give me one other summer time like that one. It was my excessive tide. Each morning, when the solar’s rays first hit the mesa high, whereas the remainder of the world was in shadow, I wakened with the sensation that I had discovered the whole lot, as an alternative of getting misplaced the whole lot. Nothing drained me. Up there alone, an in depth neighbor to the solar, I appeared to get the photo voltaic power in some direct means. And at night time, after I watched it drop down beneath the sting of the plain beneath me, I used to really feel that I couldn’t have borne one other hour of that consuming gentle, that I used to be full to the brim, and wanted darkish and sleep.

Cather poses Tom’s light-filled imaginative and prescient in opposition to his mentor’s gloom. Godfrey’s meditation in his previous home, now that his spouse, daughters, and sons-in-law have gone to Europe for the summer time, strikes a shadowy key:

He was not practically so cultivated as Tom’s previous cliff-dwellers should have been—and but he was terribly clever. He gave the impression to be on the root of the matter; Need underneath all needs, Fact underneath all truths. He appeared to know, amongst different issues, that he was solitary and should at all times be so; he had by no means married, by no means been a father. He was earth, and would return to earth. When white clouds blew over the lake like bellying sails, when the seven pine bushes turned pink within the declining solar, he felt satisfaction and stated to himself merely: “That’s proper.”

Like Cather, Wallace Stevens was a excessive priest of readability, regardless of the cryptic involution of his poetry. Those that met the poet for the primary time anticipated to see a dandy, an ornate connoisseur. The bodily Stevens stood 6-foot-2 and weighed 240 kilos. The disparity between his hulking physique and his slender acrobatic creativeness was observed by all.

Stevens might simply eat a pound of sausage at a sitting. When he requested for a martini, the waitress knew he meant a pitcher of martinis. But this gourmand was the subtlest poet America ever knew.

Uniquely amongst poets, Stevens unites the luxurious and the straight-arrow direct. He favors phrases like “poor” and “naked,” for these adjectives are emblems of necessity. But Stevens additionally has a fire-fangled vocabulary, ingenious and glistening. He tells us that Crispin, his “nincompated pedagogue” in “The Comic because the Letter C,” “hung [his eye] … on silentious porpoises, whose snouts / Dibbled in waves that have been mustachios.”

Stevens’ coruscating traces usually are not mere showmanship. Stevens’ arsenal, his phrase hoard, have to be giant and exact. He wants his inventory of marvels to fend off the deprivations of actuality.

“It’s usually stated of a person that his work is autobiographical despite each subterfuge. It can’t be in any other case,” Stevens remarked. The frustration of his loveless marriage haunts his poetry, and late in his life, so does the anticipation of demise. In “Madame la Fleurie,” Stevens sings a somber dirge for himself:

Weight him down, O side-stars, with the nice weightings of the tip.

Seal him there. He seemed in a glass of the earth and thought he lived in it.

Now, he brings all that he noticed into the earth, to the ready father or mother.

His crisp data is devoured by her, beneath a dew.

…

His grief is that his mom ought to feed on him, himself and what he noticed,

In that distant chamber, a bearded queen, depraved in her useless gentle.

The “glass” the place Stevens “thought he lived” is a picture for his poetry, right here consumed by the savage truth of mortality. Madame la Fleurie, the flowering earth, is the “bearded queen” wickedly chomping the poet (the beard is evidently grass, a morbid riffing on Whitman’s favourite picture).

Robert Frost, who survived the deaths of two kids in addition to his first spouse, measured his poet’s creativeness in opposition to harsh realities. He discovered resilience in sensible actions like mowing, mending a wall, or selecting apples. Frost’s audio system observe Emerson’s recommendation to “maintain exhausting to this poverty, nevertheless scandalous.” In a barren area, they prosper.

However Frost additionally felt a extra drastic destitution urgent in opposition to him. In “As soon as by the Pacific” Frost depicts an obliterating storm, coming to spite any sense we would have that the world is constructed to human scale:

Nice waves seemed over others coming in,

And considered doing one thing to the shore

That water by no means did to land earlier than.

Frost’s phrases are made for effectivity, frequent, and easy. The extra primary they’re, the extra crafty they appear, and the extra they frighten us.

Frost ends “As soon as by the Pacific” with pitch-black humor. Frost’s destroyer God resembles Othello telling Desdemona to “put out the sunshine” earlier than he murders her:

It seemed as if an evening of darkish intent

Was coming, and never solely an evening, an age.

Somebody had higher be ready for rage.

There can be greater than ocean-water damaged

Earlier than God’s final Put out the sunshine was spoken.

“Somebody had higher be ready for rage,” however preparation is ineffective in opposition to the darkish design of a God bent on annulling “let there be gentle.”

The plainspoken Frost marks a distinction with T.S. Eliot. Frost, like Hart Crane and Stevens (who referred to as Eliot his “useless reverse”), disliked Eliot’s Waste Land, since Eliot implied that one needs to be gloomy concerning the supposed twilight of excessive tradition, the falling off from Cleopatra on her barge to the younger man carbuncular. The tawdriness of the trendy age had been a theme of European literature since Flaubert, who each abhorred and battened on the bourgeois cesspool. But Eliot amply survives his personal snobbery, since his poetry sounds so excellent:

Allow us to go then, you and I,

When the night is unfold out in opposition to the sky

Like a affected person etherized upon a desk

Allow us to go, via sure half-deserted streets …

The invitation you obtain from Eliot’s voice is simple, as Louise Glück (who’s, together with Jay Wright, our biggest residing poet) argued in her Nobel lecture a number of years in the past. He speaks to and for you, amid scenes of loss and dereliction. Even his lacerating neuroses are magical.

Ernest Hemingway, who was maybe the best-known American author of the twentieth century, was additionally notably obsessive about failure. In “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” the dying author Harry confesses, “He had destroyed his expertise by not utilizing it, by betrayals of himself and what he believed in, by consuming a lot that he blunted the sting of his perceptions, by laziness, by sloth, and by snobbery, by satisfaction and by prejudice, by hook and by criminal.” Harry, merciless to himself and everybody else, voices Hemingway’s personal damning self-assessment.

Hemingway had a lifetime of ceaseless exercise, testing himself just like the characters in his tales. He was relentlessly aggressive—somebody remarked that few males might stand the pressure of stress-free with him for very lengthy. The damage and tear on the self is Hemingway’s key theme. “He had beloved an excessive amount of, demanded an excessive amount of, and he wore all of it out,” Hemingway writes of Harry in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” Like Fitzgerald in The Nice Gatsby and his story “The Wealthy Boy,” Hemingway is obsessive about what occurs to you when you will have made a botch of your life.

Faulkner’s curiosity in failure is simply as ardent as Hemingway’s, however he’s torrential somewhat than clipped. His prose is unstoppable as a hurricane, agonized and strident. It takes persistence to fall in love with Faulkner’s fearsome gargoyles, and power to bear the dreadful distress of The Wild Palms, Sanctuary, The Sound and the Fury, and Absalom, Absalom!, his most unsparing works. There isn’t a playful facet to him. Faulkner has no urge for food for something besides darkness. His down-at-heel indulgence in doom tapped right into a sign truth of the American character, the despair inside that provides the misinform our optimism. On the finish of The Wild Palms, the jailed abortionist Wilbourne, who has inadvertently killed the lady he beloved, refuses suicide and says, “Between grief and nothing I’ll take grief”—Faulkner’s truest assertion of his religion.

America’s tradition, like its authors, is aware of that failure is a situation, not a momentary occasion. The taint of loss soaks the blues and nation music, genres to which all People pledge allegiance at the very least a number of the time. “I attempted and I failed, and I really feel like going residence,” sang Charlie Wealthy. Rock ‘n’ roll likes to insurgent, however in blues and nation, which communicate the downhearted fact, insurrection is ineffective.

Regardless of their fame, the American modernist writers usually are not rebels. They’re reconcilers. Once we fall quick, and discover each ourselves and the universe wanting, there may be nothing left however to look at what stays, and make phrases with it.