“Man* is by Nature a migratory animal,” the aged Frederick Douglass mirrored in an 1887 speech about his world travels. “It doesn’t seem that he was meant to dwell without end in anybody locality. He’s a born traveler.”

A technology after him, Maya Angelou noticed that “you only are free when you realize you belong no place — you belong every place — no place at all.”

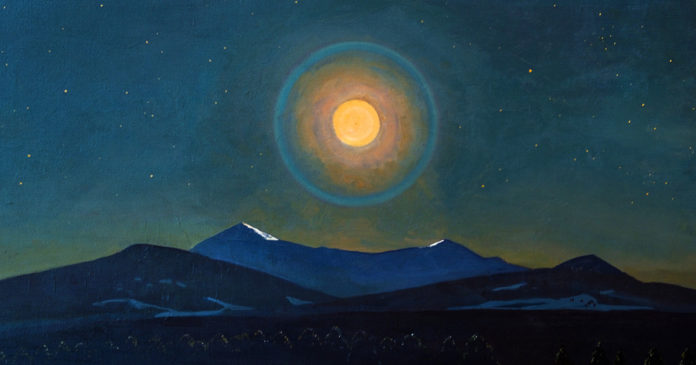

Partway in time between Douglass and Angelou, the painter, printmaker, and thinker Rockwell Kent (June 21, 1882–March 13, 1971) captured this important interaction between freedom and belonging, between nature and human nature, within the preface to Wilderness (public library) — the exquisite record of the seven months he spent on a distant Alaskan island along with his younger son within the gloaming hour of the Spanish flu pandemic and the First World Struggle, on the daybreak of his inventive life.

We every have a specific fashion of wanderlust, pulled by explicit kinds of nature that greatest converse to our personal — these locations the place we most freely lose ourselves and, in consequence, discover ourselves. For some, they’re the austere open space of blue skies and red canyons. For me, they’re the mossy old-growth forests of New Zealand and the American Pacific Northwest. For Kent, it was the extreme majesty of the Nice North:

It has all the time been laborious for me to grasp myself, to know why I work and love and reside. But it’s lucky that such issues discover a means of caring for themselves. I got here to Alaska as a result of I like the North. I crave snow-topped mountains, dreary wastes, and the merciless Northern sea with its laborious horizons on the fringe of the world the place infinite house begins. Right here skies are clearer and deeper and, for the higher wonders they reveal, a thousand occasions extra eloquent of the everlasting thriller than these of softer lands.

In a brand new preface to his journals, penned within the closing yr of his life, Kent seems to be again on the wanderlust of his youth — the roaming restlessness that had formed his spirit, the spirit from which his artwork sprang, the artwork that established him as one of the celebrated creators of his time — and exhorts the generations of wanderers to return:

Wander the place you’ll over all of the world, from each valley seeing without end new hills calling you to climb them, from each mountain prime farther peaks attractive you. At all times the distant land seems to be fairest, until you might be made ultimately a stressed wanderer by no means reaching house — by no means — till you stand at some point on the final peak on the border of the interminable sea, stopped by the finality of that.

Considering the existential pull beneath all of it — the rippling, resonant why of our wanderlust — Kent provides:

We’re half and parcel of the large plan of issues. We’re merely devices recording in numerous measure our explicit portion of the infinite. And what we take up of it makes for character, and what we give forth, for [our art].

These are salutary phrases to learn a century later, as our personal world is barely simply shaking off its straitjacket of two-year terror and changing into wanderlustable once more.

Complement with Rebecca Solnit’s wanderlusting history of walking, then revisit Kent’s breathtaking reflections on wilderness, solitude, and creativity.