The crew on the Oxford English Dictionary felt some nervousness about writing the definition for “Terf”, an acronym for trans-exclusionary radical feminist, which this month has been added to its pages. “To a sure extent, it’s like some other phrase,” says Fiona McPherson, a 50-year-old lexicographer from Grangemouth, Stirlingshire, who has labored on the dictionary since 1997. “However it will be disingenuous to say that it’s precisely the identical. There appears extra at stake. You wish to be correct, you wish to be impartial. However it’s rather a lot simpler to be impartial a couple of phrase that isn’t controversial.”

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has served as a lexical file of the world’s most generally spoken language – and its tradition – because it was based within the mid-Nineteenth century. “Put up-truth”, for instance, was the dictionary’s phrase of 2016, the yr of Brexit and Trump, whereas in 2020 it elected not to decide on one – as a result of no single phrase may sum up the pandemic expertise. Final yr, “police brutality”, “deadname”, “cancel tradition” and “anti-vaxxer” entered the dictionary for the primary time; earlier years gave us “faux information” (2019), “Silent Era” (2018) and “woke” (2017).

The June 2022 replace consists of a number of phrases that mirror our altering understanding of sexuality and gender: “multisexual”, “pangender”, “gender expression”, “gender presentation” and “enby” (derived from “NB”, which means “non-binary”), in addition to Terf. However this wasn’t, McPherson says, a acutely aware choice; moderately, these additions organically got here collectively as their utilization grew. The crew determined towards labelling Terf “offensive”, as an alternative explaining in a utilization be aware that it may be thought of so; it was felt that this “was a bit extra nuanced than simply slapping on ‘derogatory’ or ‘mainly derogatory’”.

[See also: Our words for describing the climate are changing – can they spur us to action?]

McPherson, who has a straightforward snort and a melodic Scottish lilt, is a part of a crew that has been revising the OED since 1993, their progress revealed quarterly. Outdated entries are revised, new phrases are added and those who cross from use shall be marked “uncommon” or “out of date”; altering sensibilities imply that others shall be labelled “offensive” or “derogatory”. It is a gigantic job, and one wherein I’ve an expert in addition to a private curiosity: a part of my position on the New Statesman entails sustaining our fashion information, implementing the principles of grammar and excising cliché. The selections McPherson and her colleagues make filter into these pages; on questions of spelling and which means, the crew of sub-editors I lead defers to Oxford dictionaries.

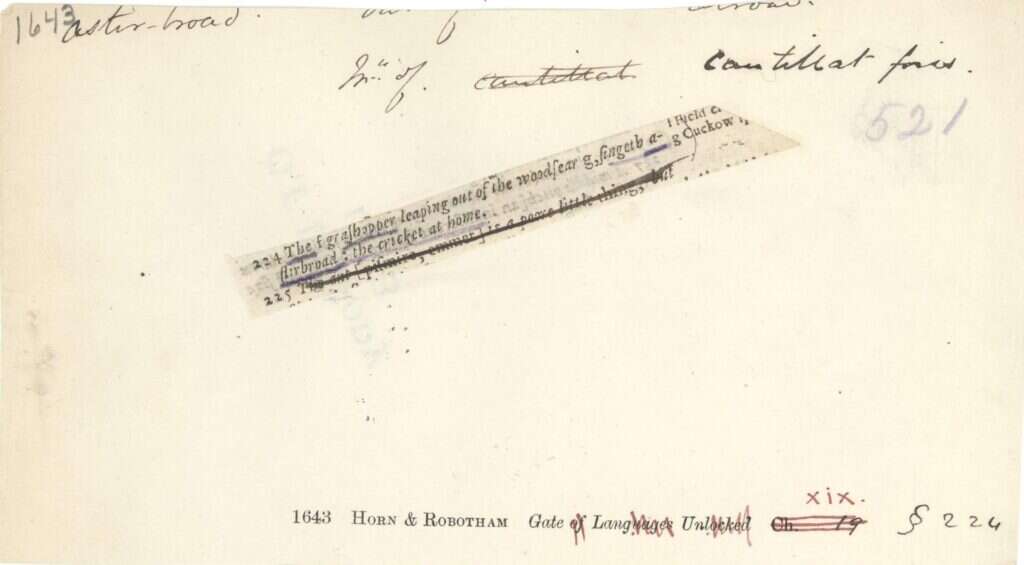

The English language evolves at such a tempo that, for the OED lexicographers, the goalposts aren’t a lot shifting as sprinting away from them. As soon as a phrase has gained its place, it could be moved – for instance, to be listed as a variant spelling – however it’s by no means taken out, which means that the dictionary solely ever expands. (That is true even of errors. The phrase “astirbroad” was added in 1885, however when an editor got here to revise it in 2019, they found that it was an early-modern typo: the typesetter for the Seventeenth-century ebook wherein the phrase was initially discovered had dropped the phrase “stir” into “overseas”. Nonetheless, astirbroad stays.) Neither is the OED restricted to British English: the dictionary consists of varieties spoken outdoors the UK – what its editors consult with as “World Englishes” – from Singapore to Jamaica.

The ensuing dictionary particulars some 600,000 phrases. The newest print version – the second, revealed in 1989 – fills 20 volumes and would set you again £862.50. The preliminary plan was to finish the third version by 2005, however 17 years later its editors are simply midway by means of. To an out of doors observer, the size of the undertaking – its grand ambition and granular element – appears virtually inconceivable, however after I put this to McPherson, she is unfazed. “We’re in hassle if the language ends, and never simply professionally,” she says. “The English language is big and so subsequently the job we’re doing is an enormous job – however I don’t discover it overwhelming. It’s energising. It’s exhilarating.”

[See also: In Ukraine, Russian is now “the language of the enemy”]

Past the sandstone facade, immaculate lawns and wisteria-fringed courtyard of the Oxford College Press constructing, within the Jericho space of the town, round 70 OED workers work in an open-plan workplace that’s humble in comparison with the august Dictionary Room its editors as soon as occupied on the Outdated Ashmolean. It’s right here in late Could that I meet McPherson and 6 of her colleagues – most of them in individual, although just a few be part of by video hyperlink (distant working on the OED pre-dated the pandemic; McPherson is predicated in Munich). Amongst them are Jane Johnson, one other Scot and a new-words editor who’s a fan of a dataset; and Bernadette Paton, an Australian former artwork trainer who has been on the OED since 1987. A decade in the past, Paton interviewed Danica Salazar, now 38, for her position as an editor; Salazar informed Paton that the OED was “doing this World English factor fallacious, and I’ll repair it” – one thing she has been doing ever since.

Once they started engaged on the third version, the crew progressed alphabetically – although they began from M, as a result of it was felt that, by that time, the editors of the primary version would have been higher established of their method. They received to the top of R earlier than rethinking. Many entries hadn’t been edited for the reason that late-Nineteenth and early-Twentieth centuries; in the event that they continued on this method, it will be a very long time earlier than they received to outdated definitions in direction of the start of the alphabet – equivalent to “digital”, the primary sense of which within the earlier version was: “Of or pertaining to a finger, or to the fingers or digits.” Such entries are generally known as precedence phrases and tagged as needing pressing consideration every time an editor comes throughout one.

The lexicographers’ work is collaborative, and it’s clear from the best way they bounce off one another in our dialog that this fits them. Editors draft in pairs, swapping entries in a type of casual peer overview, after which their phrases go to etymologists, bibliographers, the pronunciations crew, exterior consultants and finalisation editors. Step one of this course of can take something from just a few hours to some weeks, relying on the phrase: there are greater than 200 senses, for instance, of the verb “run”.

Paton remembers spending 4 weeks revising “enterprise”, the definition for which was first revealed in 1888 (“the standard or state of being busy”, which we’d now differentiate as “busyness”). “There was virtually nothing about industrial enterprise,” she says. “You had been protecting 120 years of improvement in most likely probably the most monumental space of exercise of the Twentieth century. It was hell on the time, however actually fascinating to see it on the finish.”

In 1857 a gaggle of gentleman students from the Philological Society – Herbert Coleridge, grandson of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Frederick Furnivall (immortalised by his pal Kenneth Grahame as Ratty in The Wind within the Willows), and Richard Chenevix Trench – established the Unregistered Phrases Committee, with the goal of capturing these components of the English language that had not but been recorded. Earlier makes an attempt at a dictionary had been made, however none was complete. Robert Cawdrey’s 1604 Desk Alphabeticall was the primary monolingual English dictionary, however was extra of a synonymicon; Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language, revealed in 1755, drew solely on sources revealed after 1586, omitting the lexicon of nice works from Chaucer to Bede. “Each phrase,” wrote Coleridge on the time, “must be made to inform its personal story – the story of its start and life, and in lots of instances of its demise, and even often of its resuscitation.”

However the place to start? Imagining that “a complete military would be part of hand in hand until it coated the breadth of the island”, the Unregistered Phrases Committee referred to as upon the general public to assist. In 1857 a studying undertaking was begun: the committee issued a round with directions for writing citation slips – postcard-size items of paper on which a reader, having discovered a citation in a supply that illustrated a specific utilization, would write the small print and ship them to the dictionary crew. Trench described this work as “drawing as with a sweep-net over the entire floor of English literature”.

It was, because the OED’s archivist Beverley McCulloch describes it to me, a “form of early crowd-sourcing undertaking”. The volunteer readers had been paid nothing for his or her efforts, although probably the most prolific despatched in 1000’s of quotations. The story of one among them, a Broadmoor affected person referred to as William Minor, was informed in a 2019 movie starring Mel Gibson and Sean Penn, The Professor and the Madman – tailored from a ebook by Simon Winchester. (One editor laments that the movie is “stuffed with myths”.) For girls who had been literate however prevented from looking for paid employment, the volunteer studying programme provided an approved-of occupation. “They will need to have devoted a major fraction of their lives to it,” says Peter Gilliver, a lexicographer who joined the OED on the identical day as Paton within the late Nineteen Eighties, and the creator of The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (2016).

[See also: Why the language we use to talk about the refugee crisis matters]

Anybody anticipating the OED archive to have a grand, library-like inside shall be upset (McCulloch says individuals are usually stunned to find her workplace has home windows), however the musty odor of slowly decomposing paper is pervasive. Shelving items maintain containers upon containers of the handwritten slips generated by the studying programme, some greater than 150 years previous and tied collectively in bundles. There are round 250 containers of slips that made it into the dictionary, and an extra 200 to 300 of what McCulloch calls “superfluous slips” – those who weren’t used. As soon as sorted alphabetically, the slips had been numbered in order that order may very well be restored ought to a bundle be dropped. Some have previous dictionary galley proofs or live performance programmes on the again; paper was reused, notably through the First World Warfare. Others bear quotations lower and pasted from their supply: “When you lower it on the market are not any copying errors. You could have ruined the ebook, however…” says Gilliver with a grimace.

The slips don’t bear the names of those that labored on them, however the small, exact script of JRR Tolkien, who was an editorial assistant on the dictionary from 1919 to 1920, is well recognized. The handwriting of Henry Hucks Gibbs, a benefactor who despatched in lots of quotations, sloped to the best – till he misplaced his proper hand in a taking pictures accident; after that it sloped to the left. One assistant, Arthur Maling, wrote on mud jackets, drafts of his will, even chocolate wrappers.

It wasn’t till 1879 that Oxford College Press (OUP) signed as much as publish the undertaking; it may have been the Cambridge English Dictionary, however the rival establishment’s press turned it down. As a part of the identical deal, the indefatigable lexicographer and philologist James Murray joined as editor. (Work had foundered after the demise of Coleridge, aged 30, from tuberculosis; he had lived lengthy sufficient to succeed in the phrase “abrupt”.)

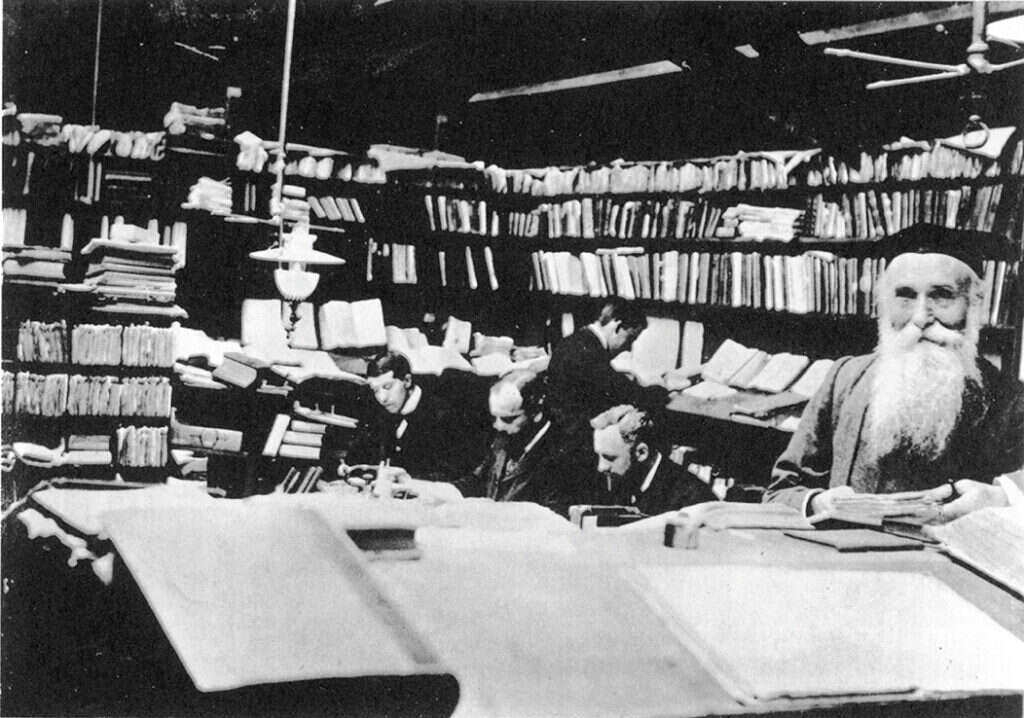

A form of corrugated iron shed was inbuilt Murray’s backyard from which his crew may work. On this “scriptorium”, round 1,000 slips arrived each day ; it took two girls greater than two years to type those who had gathered even earlier than Murray took over. The Murray kids (there have been 12) had been paid between one penny and sixpence an hour, relying on their age, to assist organise slips into alphabetical order. When an editor got here to work on a phrase they’d retrieve all of the related slips, determine a phrase’s totally different meanings and which quotations finest illustrated them, put them in chronological order, after which write the highest slip, with the definition and etymology. Later, the printers on the OUP constructing must decipher this paper patchwork, with all its crossings-out and revisions.

The deal struck between the Philological Society and OUP specified that the completed dictionary would run to 7,000 pages, and take ten years and value £9,000 to supply. However 5 years after Murray took over, he and his crew had received solely so far as “ant”. It was determined that the dictionary must be serialised to start bringing in funds, and a primary fascicle, from “A” to “Ant”, was revealed in January 1884 (the dictionary finally totalled ten such instalments). Additional editors – Henry Bradley, William Craigie and Charles Onions – had been employed to hurry progress, however Murray didn’t dwell to see the completion of his magnum opus. He died on 26 July 1915, aged 78. The final entry bearing his hand-writing is “twilight”.

By the point the entire first version was revealed in 1928, at a size of 16,000 pages, greater than 70 years had handed since Coleridge, Furnivall and Trench first fashioned their committee. It was already old-fashioned, and so a number of supplementary volumes had been revealed within the mid-Twentieth century. In 1984 OUP started a undertaking to combine the dictionary right into a single work – the second version – and to digitise its entries, an extremely bold undertaking in its time, costing $13.5m (then round £9m) over 5 years. That is the textual content whose revision occupies the crew on the OED immediately.

“Our histories, our novels, our poems, our performs – they’re all on this one ebook,” stated Stanley Baldwin, the then prime minister, at a dinner to mark the completion of the primary version. As we speak, we’d add: ads, newspapers, recipe books, journals, music lyrics, movie and TV scripts – and Twitter. Fiona McPherson displays that within the time she’s labored on the OED, “the entire concept of what’s revealed has modified”.

In contrast to the concise dictionaries as soon as present in virtually each family, the OED is a historic dictionary: it reveals how a phrase’s which means has modified over time, as illustrated by quotations – round 3.5 million in complete. (The New Statesman is cited 1,832 instances, with quotes from writers together with DH Lawrence and Doris Lessing.) It’s these that make the OED so prolonged: the 2 different best-known dictionaries of British English, Chambers and Collins, are each single-volume. Every OED lexicographer is a form of phrase detective, poring over sources, from medieval books to music lyrics, to search out the earliest instance they will of a specific sense. “It’s like making an attempt to type out the items of a jigsaw puzzle,” says Bernadette Paton. “You place the sides in first, the plain bits. After which, ‘The place does this slot in?’ and, ‘Oh, that is blue so it should be a part of the sky… Oh, no, it’s a part of the ocean.’”

Regardless of expertise, source-sifting stays time-consuming. Paton just lately drafted “what the what” as a euphemism, and sat by means of “about 30 episodes” of 30 Rock to search out its first utilization. (5 years earlier, the phrase had been positioned on the dictionary’s “phrases to observe” database after somebody heard it on the youngsters’s TV present The Wonderful World of Gumball.) That is one purpose the collaborative method is so key: one lexicographer may need the favored tradition reference that unlocks a definition for an additional. McPherson remembers drafting the entry for “burner cellphone” and courting it to an episode of The Wire, just for Paton to supply an earlier reference, in Kingpin Skinny Pimp’s observe “One Life 2 Dwell”. (Certainly one of Paton’s earliest recollections of working on the dictionary is transcribing the lyrics to the Who music “I’m a Boy” for the “headcase” entry.)

The OED depends on the collective thoughts of the general public, too. When James Murray was editor, the Put up Workplace put in a postbox outdoors his home to take care of the quantity of mail generated by the scriptorium. He wrote 30 to 40 letters a day, corresponding with figures from William Gladstone to Alfred Tennyson, looking for their experience or asking what they supposed by their use of a particular phrase. (The crew nonetheless generally receives letters addressed to Murray, greater than 100 years after his demise; on the second day of my go to, one arrives all the best way from Sacramento.)

In 1891 Murray requested the general public to inform him which syllable they emphasised within the phrase “content material” in numerous contexts; in two months he obtained virtually 400 responses. Whereas the method is now speeded by expertise, the crew continues to collect proof from the general public by means of social media and the OED web site. In 2012 they appealed for data on the origins of “to return in from the chilly”, presuming that it was utilized by the key service earlier than it made its manner into John le Carré’s The Spy Who Got here in from the Chilly. Le Carré wrote in to appropriate the file: he had coined the time period, after which the intelligence companies had began utilizing it.

The necessity for a dateable, written supply may be irritating: by the point a phrase wends its manner into the OED, it will need to have moved from speech into writing. Jane Johnson provides drafting the entry for “bucket record” for example of the delay this may create. She was solely in a position to date the phrase again to 2006, to a UPI newswire forward of the discharge of the movie The Bucket Checklist – far later than anticipated: “When you ask folks, when did ‘bucket record’ are available in, everyone is considering, ‘Oh, yeah, that was a factor after I was a youngster.’”

“It’s very true of slang and colloquial language,” provides Paton. “In the mean time we’re doing an Australian batch, and issues are developing on a regular basis. I’ll say, ‘I do know I used this within the Seventies,’ however there’s no manner of pinning it down.”

“As a result of we will’t cite: ‘Bernie within the Seventies,’” quips Danica Salazar.

“There was a joke that the primary version used to say: ‘Heard at a north Oxford tea social gathering in 1898,’” says Paton.

Twitter has proved a useful useful resource. “[Social media] is the closest factor we’ve needed to speech since we began,” says Paton, “as a result of numerous written language could be very self-conscious.” Tweets are dated and time-stamped, and can’t (at the moment) be edited after posting, making them excellent sources. Salazar, who’s from the Philippines, makes use of the instance of the adjectival use of site visitors – as in, “so site visitors” or “very site visitors” – which she knew to be frequent in Philippine English: “We are saying issues like, ‘Oh, it’s very site visitors right here immediately,’ which means there’s numerous site visitors.” When she began on the OED, she was eager to incorporate it however couldn’t discover a written utilization. “A few years in the past, we began quoting Twitter, and I looked for ‘very site visitors’, ‘so site visitors’, and we received a whole bunch of hits in sooner or later.” A Twitter person with the deal with @davidg0411 is quoted within the OED consequently.

“You may make a case for together with any lexical merchandise in a dictionary, it’s only a case of priorities,” says Johnson. “It’s a must to work out which of them appear to have probably the most worth.” Some are dropped at the dictionary’s consideration by present occasions: among the many June 2022 replace, “stealthing” (the act of eradicating a condom throughout intercourse with no accomplice’s information) was thought of after California grew to become the primary US state to make it unlawful, in October 2021. “Sportswashing” (“the usage of a sport or sporting occasion to advertise a constructive public picture for a sponsor or host”) got here to the OED’s consideration within the discourse round this yr’s World Cup in Qatar and the Beijing Winter Olympics.

The OED additionally maintains a “monitor corpus” of internet pages, totalling round 16 billion phrases, which is up to date month-to-month – a really trendy outworking of Trench’s 1857 “sweep-net”. By evaluating the phrases which were steadily utilized in latest months towards the corpus as an entire, the crew can determine that are rising in utilization. Some construct in reputation over time; others – equivalent to new senses of “bubble” and “protect” through the pandemic – abruptly spike. The crew additionally tracks failed searches on OED.com, which reveals which phrases the general public expects to search out. Each quarter, a prioritisation record is created and reviewed. On this manner, the digital is balanced by the human, the information units moderated by editorial judgement.

“There’s no magic quantity” after which a brand new phrase is added, says McPherson. “It’s not, ‘Nicely, we’ve received ten examples so we’re going to have a look at it.’ It’s breadth and depth.” The anticipated weight of proof is decrease for World Englishes. Salazar references a batch of just lately added Bermudian phrases, together with “chingas” (“used to precise shock, awe, and so on”) and “greeze” (“a big, satisfying meal”). “There are 65,000 folks in Bermuda – I believe there have been extra folks within the city the place I used to be born within the Philippines. You can not anticipate the identical quantity of proof [for Bermudian words]. However that doesn’t imply Bermudian English doesn’t deserve an area within the dictionary – actually, it’s the oldest number of English after British and American English.”

[See also: Geoff Dyer: How to grow old in America]

Do any of the lexicographers ever really feel disquiet about language change? Paton admits the usage of “of” as an alternative of “have” – “I might of” – “provides me a little bit of a jolt. [But] placing it within the dictionary wouldn’t upset me in any manner, as a result of I recognise it’s used.” We pause to look it up, and discover Charlotte Brontë is quoted as a supply. Salazar laughs: “Charlotte Brontë! She doesn’t know the way to write correct English.”

Johnson tells me a couple of wedding ceremony she attended, the place she “was sitting with folks I didn’t know in any respect and speaking a bit about what I did. The man beside me stated, ‘Oh, it sounds very sophisticated.’ And I stated, ‘Nicely, it’s sophisticated, but it surely’s doable.’ And he went off on a rant: ‘You of all folks, utilizing this phrase, doable!’” Johnson regrets that she didn’t have a comeback; a fast test finds that “doable” dates again to 1443. McPherson factors out that, equally, the primary citation for the hyperbolic use of “actually” – “for some folks, the fallacious use” – is from 1769.

Those that profess a want to “shield” the language out of affection for it could be stunned to search out that dictionary-makers don’t think about themselves arbiters of what’s “proper” and “fallacious”. Whether or not the query is about culture-wars problems with race and gender or a grammatical quibble, the reply is similar: the OED describes how language is already getting used; it doesn’t prescribe the way it must be used, nor endorse a phrase’s use. McPherson observes that the dictionary’s reliance on written sources means it’s usually “on the rearguard” of language change moderately than main the cost.

The OED’s lexicographers imagine that slang, equivalent to “bae” (June 2019) and “lol” (surprisingly late: June 2020), is worthy of inclusion – or, at the very least, they gained’t say in any other case. (One latest examine discovered that Multicultural London English, a mix of migrant influences, may change into Britain’s most important dialect inside 100 years.) “There are some issues that you just like greater than others,” says McPherson. “However as a result of the whole lot’s incomes its place, I don’t assume there’s any level at which I’ve thought, ‘Why are we placing this in?’”

The objective, she explains, is objectivity. “You all the time wish to get the whole lot over in as impartial a manner as doable, so no one would be capable to inform what you assume. When you’re engaged on a political phrase, it shouldn’t be obvious from the definition the way you vote.” Collaboration gives a type of protect towards particular person bias. Salazar says she approaches phrases with a “World Englishes” mindset, whereas Paton, who’s in her mid-sixties, appreciates the angle of the youthful members of the crew. Collectively, the hope is that these variations create as nice a level of impartiality as is humanly doable.

Having an open thoughts is crucial for the position. “While you’re a lexicographer, in case you hear a phrase that you just’ve by no means heard earlier than, you don’t go, ‘Ew, yuck, what’s that?’ You go, ‘Hmm, that’s fascinating, why did they are saying it like that?’ You wish to study extra.

“Phrases, to me, are like folks,” she continues. “There are folks I don’t like – however that doesn’t imply I don’t recognise their proper to exist.” This takes on specific significance for Salazar: “I work with varieties which might be minoritised, as a result of they’re not what we consider as ‘appropriate’ English.” She tells me a couple of lady who cried with happiness on studying that the African-American “finna” – which means “desiring to”, as in, “I finna make dinner” – had been included within the OED. “These are individuals who, for his or her entire lives, have been informed, ‘You’re lesser, you’re silly, due to the best way you converse.’ To say that, ‘No, truly, the phrases [you use] are within the dictionary’ – it has an influence on how folks see themselves.”

Ask any of my interviewees what makes for a great lexicographer and they’re going to say curiosity. Bernadette Paton describes the position as “sitting in the course of an important huge internet and sending out feelers”. I recall this remark when the OED’s chief editor, Michael Proffitt, who has labored on the dictionary for 33 years, tells me he has a “magpie type of mindset. It’s a must to be interestable in something, and it’s important to be snug with working on the limits of your information.”

Proffitt began out in comedy writing. Is there any proof of this former life? “No, the scene of the crime has been utterly cleared.” One of many phrases he makes use of to explain lexicographers is “unassuming”, and he appears uncomfortable after I ask if he sees himself as the most recent in a line of esteemed OED editors. “I’ve no sense of with the ability to compete with these figures,” he says. “I believe they’re extraordinary. Murray, notably – a polymath, a linguist, in a manner that I’m not.” Paradoxically, his humility remembers the phrases of Murray himself: “I’m a no one. Deal with me as a photo voltaic fable, or an echo, or an irrational amount, or ignore me altogether.”

Proffitt values the synergic nature of dictionary writing as a lot as the remainder of his crew do, as a result of it permits his interventions to cross unmarked. “One factor I like concerning the OED is the dearth of a byline – I just like the anonymity. You are able to do one thing that has cultural worth with out inserting your self into that tradition.” If he has a legacy, it is going to be a extra pure prose fashion: free of the constraints of print, underneath Proffitt’s editorship the OED has moved away from the “generally fairly idiosyncratic” stage of abbreviation as soon as mandated by price and practicality. “The concept the OED ought to yield its content material to the reader, and pretty readily, is vital to me. A dictionary ought to decode language, not encode it.”

The OED has by no means turned a revenue: by 1911 the college press had spent £150,000 on it and made lower than £60,000 in gross sales. As we speak’s revision programme is backed by £34m in funding, and Proffitt says revenue from OED.com subscriptions covers “numerous the editorial undertaking”. The dictionary, he provides, brings “a extra intangible reputational profit” to the college press.

What started as a traditional third version has advanced right into a undertaking divorced from the print deadlines that plagued Murray and his co-editors. However with out these constraints, the method of revision is probably limitless. Will there ever be a degree when Proffitt’s crew think about their work accomplished?

“There’ll be a degree after we say we now have revisited each single entry that was within the second version,” says Proffitt. “That shall be an vital threshold for us.” He sees the way forward for the OED as a hybrid undertaking, balancing a give attention to the extra quickly altering phrases with the objective of updating each single entry. The goal is to forestall a repeat of “the place we had been in at the beginning, which is that you’ve a totally out-of-date textual content that it’s important to revise totally once more. We wish to keep away from that cycle of renovation and dilapidation.”

Will the third version ever be revealed in print type? “We’ve not stated sure or no,” says Proffitt. “We’re a great distance from finishing. At that time, if there’s an urge for food for a print model, I’m certain we’d think about it.” It’s onerous to think about, given the expansive potentialities of the digital medium, that there shall be.

The Oxford English Dictionary stays, in some ways, a Victorian phenomenon, born in an period of outstanding innovation: of railways and steelworks, anthropology and anaesthesia, Charleses Dickens and Darwin. It’s troublesome, now, when the considered consulting a paper dictionary appears so analogue, to understand how audacious it as soon as was to attempt to seize, for the very first time, each phrase and make it inform its story.

The English language continues to twist and flex. With out the pressures of print, the reply to the query of how and the place the method of revision ends appears to be: by no means. However not one of the lexicographers I meet seems overwhelmed by this reality, nor by the size of the duty nonetheless forward. A number of specific impatience concerning the tempo – however extra as a type of greed, of the sort a reader may really feel in a bookshop, without delay hungry to eat each tome and conscious that they don’t have sufficient years to take action.

It’s unlikely that the third version shall be indirectly full inside most of the lexicographers’ working lives. Michael Proffitt doesn’t appear to thoughts this concept; he can think about a life past dictionary-making, probably involving different types of writing, and numerous listening to music. I ponder what his final phrase shall be – “unassuming”, maybe, or “twilight”, like James Murray, all these years earlier than.

[See also: New words list: OED adds ‘Terf’, ‘pangender’ and ‘vaxxer’]