To many city Individuals within the Twenties, the automotive and its driver have been tyrants that disadvantaged others of their freedom.

Right now it’s a commonplace that the car represents freedom. However to many Individuals within the Twenties, the automotive and its driver have been tyrants that disadvantaged others of their freedom. Earlier than different auto promoters, Charles Hayes noticed that trade leaders needed to reshape the site visitors security debate. As president of the Chicago Motor Membership, Hayes warned his buddies that unhealthy publicity over site visitors casualties may quickly result in “laws that may hedge the operation of cars with nearly insufferable restrictions.” The answer was to influence metropolis those that “the streets are made for autos to run upon.”

Pedestrians must assume extra duty for their very own security. However how? The place they’d been tried, authorized laws alone had been ineffective. From 1915, cities tried marking crosswalks with painted traces, however most pedestrians ignored them. A Kansas Metropolis security professional reported that when police tried to maintain them out of the roadway, “pedestrians, a lot of them girls” would “demand that police stand apart.” In a single case, he reported, “girls used their parasols on the policemen.” Police relaxed enforcement.

Metropolis individuals noticed the automotive not simply as a menace to life and limb, but in addition as an aggressor upon their time-honored rights to metropolis streets. “The pedestrian,” defined a Brooklyn man, “as an American citizen, naturally resents any intrusion upon his prior constitutional rights.” Customized and the Anglo-American authorized custom confirmed pedestrians’ inalienable proper to the road. In Chicago in 1926, as in most cities, “nothing” within the regulation “prohibits a pedestrian from utilizing any a part of the roadway of any road or freeway, at any time or at anywhere as he might want.” So famous the writer of a site visitors survey commissioned by the Chicago Affiliation of Commerce. Based on Connecticut’s first Motor Automobile Commissioner, Robbins Stoeckel, probably the most restrictive interpretation of pedestrians’ rights was that “All vacationers have equal rights on the freeway.”

A Kansas Metropolis security professional reported that when police tried to maintain them out of the roadway, “pedestrians, a lot of them girls” would “demand that police stand apart.”

Conversely, the motorist’s declare to rights on the street on the expense of pedestrians was very laborious to make. By regulation and by customized, all had a proper to the road, and none may use it to the detriment of others’ rights. In 1913 the New York Courtroom of Appeals noticed that it was “widespread information” that the “nice dimension and weight” of cars may make them “a most severe hazard,” and so the duty for preserving the security of the streets lay overwhelmingly with motorists. In New York Metropolis’s site visitors court docket in 1923, a decide defined that “No person has any inherent proper to run an vehicle in any respect.” Quite, “the courts have held that the precise to function a motorcar is a privilege given by the state, not a proper, and that privilege could also be hedged about with no matter limitations the state feels to be crucial, or it could be withdrawn totally.” The regulation wouldn’t deprive pedestrians of their customary rights in order that motorists may roam at will in cities.

By customized the road had all the time been free to all; the regulation had intervened solely within the names of security and fairness. Fairness may demand, for instance, that nobody hinder the roadway with standing autos. But quick and harmful cars imperiled pedestrians’ conventional proper. It didn’t make sense to most metropolis individuals to guard the pedestrian majority by curbing this proper and turning the pavement over to motorists. A Philadelphia newspaper editor reproached motorists for usurping “pedestrians’ rights” by passing standing streetcars and stopping pedestrians from crossing streets.

Readers’ letters to the St. Louis Star specific pedestrians’ indignation at motorists’ intrusion upon their rights. One letter, signed “Pedestrian,” complained that “the pedestrian is pressured to undergo the tyranny of the automobilist.” Different letter writers urged pedestrians to arrange to defend their declare to the streets. “It is perhaps crucial to arrange an antiautomobile league,” wrote one. “The time is ripe for the widespread individuals and the pedestrian to arrange,” wrote one other. “We should all pull collectively,” wrote a 3rd, and “insist on our rights to make use of the streets” till the “auto-hogs . . . get up to the truth that they can not do as they please and monopolize the streets.”

Native police tended in charge motorists for pedestrian site visitors casualties. With their conventional mission of defending customized and searching for fairness, police have been unwilling to abridge pedestrians’ rights to the free use of metropolis streets. New York police Justice of the Peace Bruce Cobb in 1919 defended the “authorized proper to the freeway” of the “foot passenger,” arguing that “if pedestrians have been at their peril confined to road corners or sure designated crossings, it would have a tendency to present egocentric drivers too nice a way of proprietorship within the freeway.” He assigned the duty for the security of the pedestrian — even one who “darts obliquely throughout a crowded thorofare” — to drivers. Most American police would have agreed with the Ontario authorities who regarded pedestrians as victims of “an unlucky perspective of thoughts which belongs to some drivers and which assumes that the pedestrian ought to get out of the way in which of the automobile.”

Police and judicial authorities acknowledged pedestrians’ conventional rights to the streets. “The streets of Chicago belong to town,” one decide defined, “to not the automobilists.” Some even defended kids’s proper to the roadway. As a substitute of urging mother and father to maintain their kids out of the streets, a Philadelphia decide attacked motorists for usurping kids’s rights to them. He lectured drivers in his courtroom. “It received’t be lengthy earlier than kids received’t have any rights in any respect within the streets,” he complained. Because the usurper, the motorist, not the kid, ought to be restricted: “One thing drastic should be performed to finish this menace to pedestrians and to kids specifically.”

As is perhaps anticipated, judges tended to defend customs of road entry. A Philadelphia newspaper declared that as a basic rule, “indignant judges inform the typical driver who is named earlier than them that ‘they and their contraptions ought to be pushed from the streets.’” In 1921 an Illinois decide struck down Joliet’s requirement that pedestrians cross streets at proper angles or on crosswalks, and that pedestrians observe different site visitors guidelines. In 1926 a Detroit decide admitted that in accident circumstances “his sympathies have been all the time with the pedestrian, and {that a} driver of a motorcar which had prompted damage to a pedestrian, coming earlier than him in his court docket may anticipate as extreme therapy because the regulation would allow him handy out.” One other Justice of the Peace lectured an errant motorist for threatening to make America a “race of cripples.” Upon convicting a truck driver of manslaughter he declared: “Such individuals as you’re a shame to humanity.” Even the extraordinary site visitors police received a repute for hostility to the motorist. The director of police in Philadelphia was pressured to remind his officers publicly that well-intentioned drivers who neglected one of many metropolis’s many motoring guidelines “shouldn’t be handled as pace maniacs or criminals.”

Juries tended to favor pedestrians as effectively. “Juries in accident circumstances involving a motorist and a pedestrian nearly invariably give the pedestrian the advantage of the doubt,” a security professional defined in 1923; “the coverage of the typical juryman is to make the car proprietor pay, no matter duty for the actual accident.”

Most of the time, the press took a lot the identical view. The main metropolis paper in Syracuse, New York, argued that the burden of security lay correctly with motorists. “The general public, for probably the most half, just isn’t so enormously in want of fixed warnings towards the risks of the streets.” The New York Instances claimed in 1920 that pedestrians’ rights to the streets have been so intensive that “as a matter of each regulation and morals they’re underneath no obligation” to train “all attainable care.” The larger share of duty (ethical and authorized) lay with the motorist: “drivers justly are held to a larger care than pedestrians,” the paper contended. Pedestrians “have rights within the streets, even tho they select to cross elsewhere than on the appointed locations.” The Outlook agreed {that a} increased order of justice was at work than the merely authorized. Motorists have a “ethical duty” on the street, a duty too few have been fulfilling.

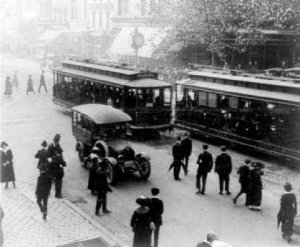

Earlier than the American metropolis may turn out to be a largely automotive metropolis, the car needed to win a superior proper to many of the road’s floor. Except it succeeded on this declare, in crowded cities these motorists who have been unwilling to run down pedestrians can be pressured to a digital standstill. But earlier than 1920 American pedestrians crossed streets wherever they wished, walked in them, and let their kids play in them. The extent of those practices was such that in one of many first organized road security campaigns in 1914, the Chamber of Commerce, in Rome, New York, needed to ask pedestrians to not “go to on the street” and to not “manicure your nails on the road automotive tracks” — with restricted success. Below these circumstances, an automotive metropolis appeared a dim prospect.

The transformation was not a pure evolution, a aspect impact of technological progress, the selection of a democratic majority, or the product of a free market. Regardless of centuries-old cultural and authorized legacies that led to solutions unfavorable to cars in cities, automotive curiosity teams developed a optimistic case for brand new methods to battle site visitors accidents and congestion, coinciding with their new self-identification as “motordom.” It was a strategic effort waged on three fronts: legal guidelines, social norms, and engineering requirements. Usually the proponents of the motor age introduced their place clothed in a rhetoric of freedom. From American beliefs of political and financial freedom, motordom normal the rhetorical lever it wanted. In these phrases, motorists, although a minority, had rights that protected their selection of mode from intrusive restrictions. Their driving additionally constituted a requirement for road house, which, like different calls for in a free market, was not a matter for professional scrutiny.

From American beliefs of political and financial freedom, motordom normal the rhetorical lever it wanted.

The wrestle was tough and typically fierce. In motordom’s manner have been road railways, metropolis individuals afraid for the safety of their kids within the streets, and many of the established site visitors engineering ideas of the Twenties. Motordom, nonetheless, had efficient rhetorical weapons, rising nationwide group, a good political local weather, substantial wealth, and the sympathy of a rising minority of metropolis motorists. By 1930, with these property, motordom had redefined town road.

Within the new mannequin, some customers of as soon as unquestioned legitimacy (notably pedestrians) have been restricted. Site visitors engineers now not burdened motorists with the duty for congestion; their aim now was to ease the movement of motor autos, both by limiting different customers or by rebuilding metropolis thoroughfares for vehicles. New city roads have been handled as shopper commodities purchased and paid for by their customers and to be equipped as demanded. On this foundation, over the next 4 many years, town was remodeled to accommodate cars.

Peter Norton is affiliate professor of historical past within the Division of Engineering and Society on the College of Virginia. He’s the writer of “Autonorama: The Illusory Promise of High-Tech Driving” (Island Press) and “Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City,” from which this text is tailored.