***

What follows will probably be specific as a result of it’s about expletives; it could additionally appear offensive, as a result of it’s about how phrases have grow to be so.

***

I stumbled upon this query as a historic guide for a brand new drama set within the Sixteenth century, when I wanted to evaluate whether or not sure curse phrases within the script would have been acquainted to the Tudors. The revelation – given away within the title of Melissa Mohr’s fantastic ebook Holy Sh*t – is that every one swear phrases concern what’s sacred or what’s scatological. Within the Center Ages, the worst phrases had been about what was holy; by the 18th century they have been about bodily features. The Sixteenth century was a interval when what was thought-about obscene was in flux.

Essentially the most offensive phrases nonetheless used God’s title: God’s blood, God’s wounds, God’s bones, demise, flesh, foot, coronary heart, arms, nails, physique, sides, guts, tongue, eyes. A statute of 1606 forbade using phrases that ‘iestingly or prophanely’ spoke the title of God in performs. Rattling and hell have been early trendy variations of such blasphemous oaths (bloody got here later), as have been the euphemistic asseverations, gad, gog and egad.

Many phrases we take into account, at finest, crude have been medieval common-or-garden phrases of description – arse, shit, fart, bollocks, prick, piss, turd – and weren’t thought-about obscene. To say ‘I’m going to piss’ was the equal of claiming ‘I’m going to wee’ as we speak and was politer than the brand new Sixteenth-century vulgarity, ‘I’m going to take a leak’. Placing physique components or merchandise the place they shouldn’t usually be created delightfully defiant phrases reminiscent of ‘turd in your tooth’, which seems within the 1509 compendium of the Oxford don John Stanbridge. Non-literal makes use of of those phrases – which is what tends to be required for swearing – like ‘take the piss’, ‘on the piss’, ‘piss off’ – all appear to be Twentieth-century thrives. For the latter, the Tudors would have substituted one thing diabolical – ‘the satan rot thee’ – or epidemiological – ‘a pox on you’.

However the scatological was beginning to grow to be obscene. Sard, swive and fuck have been all barely impolite phrases for sexual activity. An early recorded use of the f-word was a bit of marginalia by an nameless monk writing in 1528 in a manuscript copy of Cicero’s De officiis (a treatise on ethical philosophy). The inscription reads: ‘O d fuckin Abbot’. On condition that using the f-word as an intensifier didn’t catch on for one more three centuries, that is possible a punchy touch upon the abbot’s immoral behaviour.

Frig and jape have been additionally on the cusp of offensiveness. Randle Cotgrave’s 1611 French-English dictionary interprets the French fringue as ‘to lecher or lasciviously frig with the tail’ (tail was a euphemism for penis). Cunt was additionally beginning to transfer from being essentially the most direct phrase to explain part of the anatomy into obscenity. Shakespeare makes jokes in Hamlet about ‘nation issues’ by which he clearly means (as the subsequent line says) what ‘lie[s] between maids’ legs’. Bugger remained a non-explicit phrase for anal intercourse.

Immediately many of those phrases have an admirable grammatical flexibility for which the Tudors had no clear substitute. For a phrase to specific unlucky circumstances that appear unattainable to beat (‘we’re fucked’), the Historic Thesaurus of English tells us that they’d have proclaimed themselves to be ‘in scorching water’ (first use 1537), ‘in a pickle’ (1562), ‘in straits’ (1565) or, in essentially the most excessive predicament, at one’s ‘utter shift’ (c.1604). To ‘fuck up’ or spoil one thing, they’d have used ‘to bodge’ or ‘to botch’. To say one thing was codswallop, baloney, bollocks, they’d have gone with trumpery, baggage, garbage or the fantastic reduplicating phrases that seem within the 1570s and 80s: flim-flam, fiddle-faddle, or fible-fable.

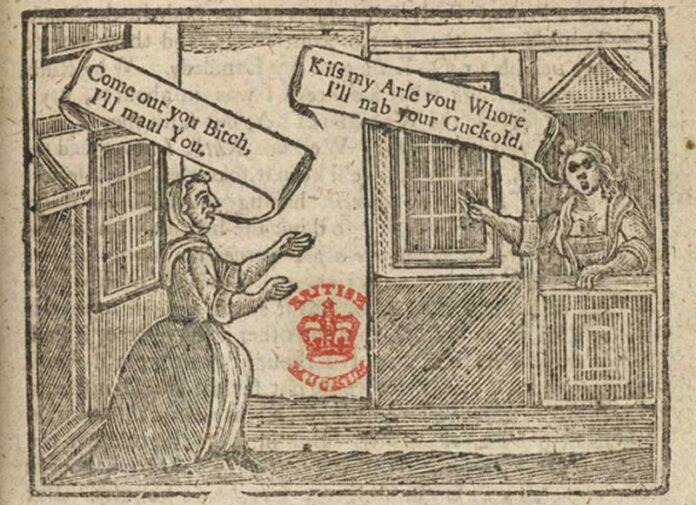

However, holy phrases apart, in case you actually wished to offend somebody within the Sixteenth century, you’d name them a whore, knave, thief, harlot, cuckold, or false. They nonetheless cared extra about a popularity for behaving badly than learn how to describe the behaviour itself.

Suzannah Lipscomb is creator of The Voices of Nîmes: Girls, Intercourse and Marriage in Early Fashionable Languedoc (Oxford College Press, 2019), host of the Not Simply the Tudors podcast and Professor Emerita on the College of Roehampton.