Content material

This content material may also be considered on the location it originates from.

I keep in mind the primary time I encountered a pierced eyebrow. I used to be sixteen, travelling with the talk staff from my highschool within the quiet suburbs of Bangalore to the busy metropolis middle for a regional meet. I had managed to get the staff collectively solely by promising the opposite boys that there can be women there. However the women we had been ranged in opposition to, who went to a “progressive” college for which we had an unreflective contempt, had been creatures from one other world. All of them wore a type of shapeless tie-dyed garment that couldn’t be a part of any uniform, spoke in a slack, nearly American drawl, and, with their air of informal privilege, had been amused by our prissy diction—our try-hard concept of what correct English was imagined to sound like—and our evident lack of ease round them.

Being effectively practiced, we gained the talk. However, chatting with the women afterward, we discovered that they disdained our pleasure in victory, together with our hand-me-down polyester ties and blazers, our an identical short-back-and-sides haircuts. I awkwardly requested the one with the pierced eyebrow whether or not her piercing had a “which means.” She smirked a little bit. “Self-expression,” she mentioned. “However what does it specific?” I requested, totally in earnest. She repeated herself very slowly, as if to a complete doofus, “Self. Expression.”

I assumed that I’d finally perceive what she meant, however even now I’m undecided I do. The episode got here to thoughts as I learn Andrea Wulf’s “Magnificent Rebels: The First Romantics and the Invention of the Self” (Knopf). Wulf’s e-book issues a interval, from the mid-seventeen-nineties to the early eighteen-hundreds, when Jena, a small German city on the river Saale, turned dwelling to a formidable coterie. Right here, she writes, was “a gaggle of novelists, poets, literary critics, philosophers, essayists, editors, translators and playwrights who, intoxicated by the French Revolution, positioned the self on the centre stage of their pondering.”

There now we have that peculiar factor, “the self.” Wulf generally permits us the German unique: “The Ich, for higher or worse, has remained centre stage ever since. The French revolutionaries modified the political panorama of Europe, however the Jena Set incited a revolution of the thoughts.” If Wulf is correct, the woman with the pierced eyebrow was a part of an unfolding world-historical drama that started on the banks of the Saale.

Within the method of such works—and in step with the Ich philosophy that she chronicles—Wulf tells us a good quantity about her personal self. I found that she was, like me, born “within the riotous colors of India”; studied, as I did, philosophy in faculty, a topic that pulled her “into an intoxicating world of pondering”; and now lives, as I do, in London, “a giant soiled metropolis full of individuals.”

Wulf had, as I didn’t, mother and father who taught her “to observe my goals,” having finished so themselves once they left Germany to do public-spirited work in India. She had a daughter when she was twenty-two and moved, when that daughter was six, from Germany to England: “It was a snap resolution. I stop my research, offered my few possessions and moved to London.” Wulf was “a single mom with a half-finished training, a trunk stuffed with books, no revenue, and a seemingly unending provide of confidence,” she writes. “Possibly a few of the decisions had been reckless, however they had been mine.”

She acknowledges, after all, that each one this spontaneity rested on “the privilege of realizing that if all of it went incorrect, I might at all times have been in a position to knock on my mother and father’ (middle-class) door.” A substantial amount of freedom, it’s clear, got here from her “intelligent, liberal, loving and tutorial mother and father” and from her E.U. passport. Maybe the explanation I’m reluctant to affix her ardent advocacy for the Jena Set has one thing to do with the methods wherein my very own path to philosophy differs from hers: no E.U. passport and solely a grim told-you-so awaiting me on the opposite aspect of a knock on the parental door.

The thinker Johann Gottlieb Fichte is meant to have declared in his first lecture at Jena that “an individual needs to be self-determined, by no means letting himself be outlined by something exterior.” Let’s put apart the truth that the world, with its passport controls and its subtler hierarchies, makes not being “outlined by something exterior” a tougher activity for some folks than for others. Does the broader Romantic fixation on the autonomous self make sense the place it issues?

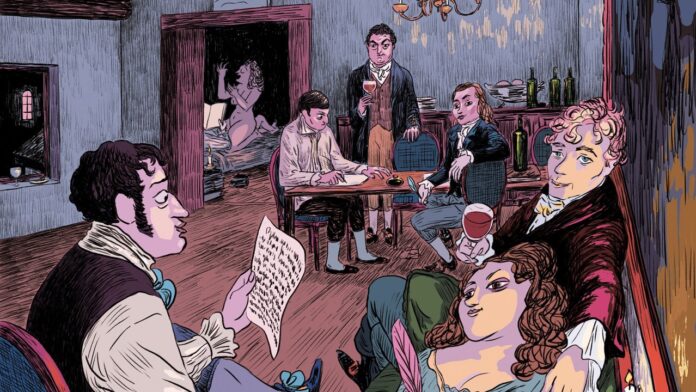

“Magnificent Rebels” is a buoyant work of mental historical past written as what was as soon as termed the “increased gossip.” Wulf’s story, because the film adverts used to say, has every part. There’s the good-looking younger poet in love with a sickly pubescent woman; the good lady whose literary work was credited to the lads in her life; the passionate friendships shattered into fierce feuds. There are writers who wrestle to write down and others who wrestle to cease. A gentle and ominous undertone to all of the cogitation and copulation is the rise of Napoleon, a Romantic determine in his personal manner, from the ashes of the 1789 revolution in France.

Such drama, such freedom—in so small a city, and in so unfree an age. How was it potential? Wulf believes that the environment of mental and (to some extent) political freedom was sustained by the sheer problem of censorship in a “splintered and inward-looking” Germany, nonetheless a “patchwork of greater than fifteen hundred states,” within the dying days of the Holy Roman Empire. Thinkers and writers of a progressive stripe had been drawn to Jena by what an older member of Wulf’s ensemble, Friedrich Schiller, described as the bizarre prospect of “full freedom to suppose, to show and to write down.” And, after all, to learn the books, newspapers, and pamphlets pumped out by a thriving publishing commerce.

The background to the brand new Ich philosophy was the revolutionary work of Immanuel Kant. He was now coming into his eighth decade, however his writings had been nonetheless being mentioned by readers in Jena, Wulf tells us, “with the identical ardour as others did widespread novels.” “What’s Enlightenment?” Kant had requested, answering—in a phrase that also retains one thing of its unique spine-tingling energy—that it was nothing roughly than “man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity.” Extra pithily, he challenged his contemporaries, “Dare to know.”

Kant had primed folks to deal with how their data of the world was conditioned by their minds; in Wulf’s précis, “We’ll at all times see it by way of the prism of our pondering.” Even time and area weren’t “precise entities” however, fairly, belonged to “the subjective structure of the thoughts.” They had been, as Wulf places it, the “lens by way of which we see nature.” We had been to tell apart, then, between a factor as we understand it and the “thing-in-itself.”

Ever since Fichte learn Kant’s “Critique of Practical Reason” in 1790, annotating frenetically as he went, he had, he declared, “been dwelling in a brand new world.” He was moved, it appears, by a grand image of the self as “a lawgiver of nature,” a conception that encourages what Wulf vaguely phrases “a shift in direction of the significance of the self.” Fichte wished to develop the position of the Ich nonetheless additional, eradicating its blindfold and abolishing the concept of an inaccessible thing-in-itself; the self after Kant turned “inventive and free.”

The rhetoric of freedom and self-determination should have appealed to the younger Fichte, the son of a ribbon-weaver in Saxony. He had gained a spot at an élite boarding college after a beneficent visiting baron heard him recite, from reminiscence, a sermon that he had listened to when he was taking care of livestock by a church. Fichte remade himself within the time-honored manner, unlearning his rube’s accent and marrying a civil servant’s educated daughter. But amid his dense metaphysical publications was a pamphlet, circulated in 1793 (and prudently unsigned), extolling the revolution in France. “Simply as that nation has torn away the exterior chains of man,” he wrote later, “my system tears away the chains of the thing-in-itself, or exterior causes, that also shackle him roughly in different techniques, even the Kantian. My first precept establishes man as an impartial being.”

Arriving on the College of Jena in 1794, Fichte started to domesticate a messianic persona. “Gents, go into yourselves,” he shouted from his lecturer’s pulpit. (To guage by Wulf’s verbs—“thundered,” “roared,” “bellowed”—Fichte had no indoor voice.) “Act! Act!” he exhorted. “That’s what we’re right here for.” He left the auditorium adopted by a gaggle of reverent college students, “like a triumphant Roman emperor.”

For long-suffering readers of his treatises, the adulation that Fichte impressed is difficult to grasp. Maybe one wanted to be there, to really feel the drive of his presence, his prophet’s method. Little else might clarify how folks saved a straight face at such pronouncements as “My will alone . . . shall float audaciously and boldly over the wreckage of the universe.”

What’s simpler to know is the human attraction of the opposite figures who populate the pages of this e-book. They had been, after all, the unique Romantics, at a time when the German phrase for the sensibility (romantisch) hadn’t but acquired its fashionable significance. One would possibly name Wulf’s telling novelistic, though solely a nineteenth-century Russian novelist would have a forged of protagonists with such inconveniently comparable names: Friedrich Schiller, Friedrich Schelling, Friedrich Schlegel. There may be one other Friedrich—von Hardenberg—who wrote beneath the title Novalis. There are two Johanns and two Carolines. Wulf and her publishers have gone a number of additional miles to assist the reader maintain all of them straight: informative chapter titles, a cautious index, and a dramatis personae with minibiographies.

Looming over the younger blood of Jena was that nationwide icon Goethe, who, early in Wulf’s e-book, rides picturesquely from his dwelling in Weimar to his buddies in Jena on a sizzling summer season’s day throughout wheat fields at harvest time. His youthful novel “The Sorrows of Young Werther” (1774) had captivated a technology a few many years earlier; in imitation of the title character, readers wearing yellow waistcoats and breeches. Imitation didn’t cease there: so many younger males had been mentioned to have taken Werther’s lovelorn instance to coronary heart and killed themselves that, Lord Byron jested, Goethe had claimed extra lives than Napoleon. By the seventeen-nineties, Goethe was a senior statesman, much less a member of the Jena Set than its “benevolent godfather.” However it was his buddy Friedrich Schiller, the celebrated playwright, who persuaded him to take thinkers like Fichte severely. Goethe had thought of himself a realist, devoted to the statement of nature; Schiller was inclined towards idealism, and the inward-turned interrogations of the soul.

By the mid-seventeen-nineties, the brothers Schlegel—August Wilhelm and Friedrich—had been additionally in Jena. So had been the brothers Humboldt—Wilhelm and, on common sojourns, Alexander (the topic of Wulf’s earlier e-book). Schelling had survived his early years as a toddler prodigy and, later, enrollment at a forbiddingly austere Protestant seminary to publish work wherein he argued that the Ich was an identical with nature. The dashing Novalis visited when he might, sharing his hopeless love for a dying woman together with his buddies, together with the poetic-philosophical fragments that made him well-known. His will be the most resonant formulation of the Romantic essence: “By giving the commonplace the next which means, by making the bizarre look mysterious, by granting to what’s recognized the dignity of the unknown and imparting to the finite a shimmer of the infinite, I romanticise.”

A lot for the lads. The ladies are equally exceptional, none extra so than Caroline Böhmer Schlegel Schelling. (She was married to August Wilhelm Schlegel for seven years after which to Friedrich Schelling for six.) She was important to, though by no means correctly credited for, what have turn into canonical German translations of Shakespeare. “She ticked syllables, tapping her fingers on the desk as she remodeled August Wilhelm’s textual content into melody and poetry,” Wulf writes. Her marriage to Schlegel, in 1796, was her second, and got here after a few years of her rejecting him. “Schlegel and me! No, nothing goes to occur between us,” she mentioned, like a rom-com heroine resisting the inevitable. She finally determined that he is likely to be simply the factor in any case, however not earlier than a number of rumored affairs, a being pregnant that resulted from a one-night stand after a ball, and a stint in jail for suspected revolutionary sympathies.