On 2 March 1901, the Buddhists of Rangoon (at present’s Yangon) in Burma celebrated the complete moon competition, the most important of the yr. Guests, respectfully barefoot, stuffed the grounds of the massive gold-plated Shwedagon Pagoda, the nation’s most vital Buddhist pilgrimage web site, its glimmering spire seen from miles away. On the platform, individuals have been chanting, meditating, providing candles, flowers and water, speaking. The encompassing streets have been alive with meals stalls, music and drama performances, banners and decorations. Within the midst of those crowds and celebrations, an act of profound civil disobedience happened: a shaven-headed Buddhist monk stepped out in entrance of an off-duty colonial policeman, within the make use of of the British Empire, and ordered him to take off his sneakers.

We are able to think about the ripple that unfold as individuals seen the confrontation. Wrapped within the saffron robes of faith, the monk was not simply difficult one policeman. His protest focused the facility of the empire, the most important the world had ever seen.

Information of this act unfold from the Rangoon bazaars into the Burmese newspapers. It sparked makes an attempt by the colonial authorities to regulate the state of affairs, adopted by additional polemics and confrontations, and launched the ‘shoe concern’ as a rallying-point for Burmese anticolonialism for the subsequent twenty years. When Barack Obama visited the Shwedagon greater than a century later, he did so barefoot.

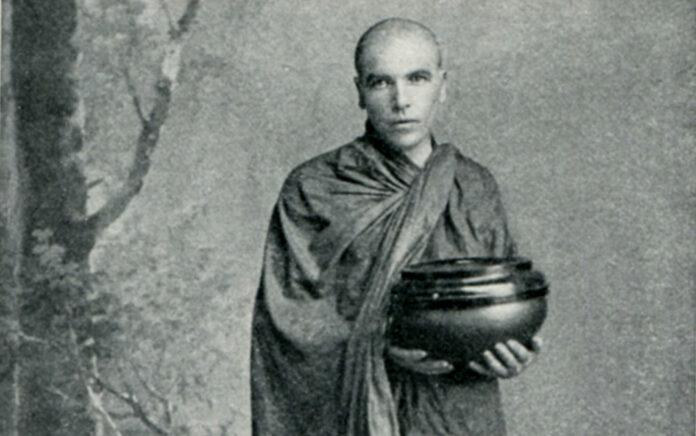

Who was the monk that began all of it? The eyes that stared down the policeman have been the blue eyes of the mysterious ‘Irish Buddhist’ from Rangoon’s Tavoy monastery, recognized to many by his Buddhist identify of U Dhammaloka. What was his unique identify? The place had he come from? And what was an Irish-born man doing as a Buddhist monk, in Rangoon, difficult imperial energy beneath a full moon?

Even in his personal day, Dhammaloka was no simple man to pin down, regardless of the very best efforts of the colonial police and intelligence providers. He used a minimum of 5 aliases and unnoticed about 25 years of his previous within the very totally different tales he instructed. It took me and my co-authors Alicia Turner and Brian Bocking a decade to place collectively the items in our book The Irish Buddhist (2020) – however, in tracing his life, we rediscovered a rare biography that provides a window on the crowds, networks and social actions that introduced in regards to the finish of empire in Asia.

Burma had been conquered by Britain in three wars, the ultimate one adopted by a brutal counterinsurgency within the late Eighties, somewhat greater than a decade earlier than the confrontation in Rangoon, the colonial capital and port metropolis from the place Burma’s wealth was shipped abroad. Because the Indian rebellion of 1857-59, European colonisers in Asia have been uncomfortably acutely aware of simply how few they have been. In colonised Burma, as elsewhere, nice efforts went into intensifying racial hierarchies, marking off the small numbers of whites and their colonial officers from the tens of millions of ‘others’ they dominated over: Burman Buddhists, Indian Muslim dockworkers, the Chinese language diaspora, Tavoy sailors, Shan and different ethnic minorities. Empire was not simply army energy and financial exploitation. It was additionally, crucially, cultural hierarchy.

Clothes – particularly sneakers – was key to the imperial color line. In Burma, like a lot of Asia, sneakers are thought of soiled. They aren’t worn inside homes, not to mention in sacred areas, as an indication of primary respect. For whites and representatives of the Empire, just like the off-duty policeman, to take off one’s sneakers would have meant reducing oneself to the extent of the barefoot or sandal-wearing lots: not simply personally humiliating however harmful to imperial energy, which relied on consistently reinforcing racial, cultural and institutional hierarchies. When poor whites ‘went native’ – settling down with native companions, taking informal labour alongside Asians, sporting the identical garments as their neighbours and coworkers – it marked a harmful breach in white solidarity.

A European Buddhist – somebody who went so far as changing to a neighborhood faith, bowing all the way down to ‘heathen idols’, maybe a monk or nun ritually subordinated to an Asian spiritual hierarchy, begging for meals and naturally barefoot, shaven-headed and sporting robes – epitomised this breakdown of racial hierarchies. Rudyard Kipling’s novel Kim (1901), which tells the story of the orphaned son of an Irish soldier, introduced up in a Lahore bazaar and following a Tibetan Buddhist guru, was a bestseller that helped win its creator the Nobel Prize.

Did the empire really respect Burmese spiritual sensitivities, in their very own holy locations – or not?

Empire and faith have been deeply intertwined: ‘bringing the Gospel to the heathen’ was a key justification of colonialism (alongside claims acquainted at present: bringing fashionable science and schooling, rescuing ladies, or bringing rational authorities). The imperial institution belonged to authorised Christian denominations, and in 1901 the missionary effort was near its peak, supplementing the brute power of army energy and colonial legislation with the delicate energy of conversion and Christian colleges (run in English and supported by the state).

But this introduced dangers for a colonial energy that needed to proclaim itself formally impartial round faith, keen to rule Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, Christians and others with out worry or favour. By highlighting sneakers in pagodas, Dhammaloka put his finger on this contradiction. Did the empire really respect Burmese spiritual sensitivities, in their very own holy locations – or not? Both reply was dangerous for the buildings of imperial and racial energy.

This weak level had lengthy been probed in colonised Eire, the place the Emancipation motion had asserted the rights of the Catholic Irish towards the Protestant institution to nice impact within the 1820s, enabling nationwide self-assertion and political organising underneath the safety of native faith, which British colonial authorities couldn’t be seen to assault immediately. Later within the century, mass participation within the Land Conflict ended the (largely Protestant) aristocracy, and noticed their (principally Catholic) tenants coming to personal the land they labored, whereas the ‘Irish Celebration’ grew to become more and more vital in Westminster.

On the similar time, the Irish have been leaving the island. Of the 8 million earlier than the catastrophic 1845-49 famine, 1,000,000 died and one other million emigrated within the following decade; emigration finally introduced the inhabitants down to only over 4 million, because the younger left for the factories of Boston or Birmingham, for Australia or Canada. One in every of these was the boy who would grow to be ‘U Dhammaloka’.

But who was he? The reply shouldn’t be simple to untangle. Historical past, after all, is written by the winners – and the colonial newspapers which can be the most typical sources for his life have been written for and by individuals who had dedicated themselves to colonialism, changing into colonial officers, troopers, missionaries and others, and transferring to Asia to grow to be a part of the imperial construction. Dhammaloka was additionally a working-class radical who sailed very near the wind. His a number of aliases and lacking years are frequent in a time the place mugshots and fingerprints have been widespread as instruments for state surveillance of the migrant poor; masking his tracks every time doable was smart behaviour. We are able to hint his life solely due to the massive strides made in digitising newspapers, books and archives in recent times. It seems that his story crosses a minimum of 12 totally different nations.

Regardless of his aliases, the identify ‘Laurence Carroll’ suits with a beginning in 1856 within the shadow of the church at Booterstown, a village changing into a suburb, an hour’s stroll south from the Dublin docks (his identify was additionally confirmed by an Irish journalist in Singapore). Carroll was the youngest of six. He left faculty round 13 and emigrated to Liverpool. Discovering work in a ship’s pantry, he’s recorded as arriving in New York in 1872. He labored on cargo ships up and down the East Coast earlier than changing into a ‘hobo’ (a migrant employee) and travelling west, leaping trains and making his approach through Chicago and Montana to the fruit boats of the Sacramento River and finally the San Francisco docks.

Dhammaloka’s anti-racism was in all probability chosen on this lengthy journey. Liverpool docks have been contested between English and Irish staff. New York and the hobo trails, following the US Civil Conflict, noticed many Irish ‘changing into white’, utilizing ethnic solidarity and racism to cement their place on the expense of Black individuals. He handed by way of Montana within the interval between Purple Cloud’s Conflict and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Northern California – and the San Francisco docks – have been websites of anti-Chinese language racism however, all through his later life, we see a refusal of racism and a constant selection of cross-racial solidarity a few years within the making.

Someplace alongside the way in which, he additionally picked up the talents and concepts of late-Nineteenth-century radicalism, which he would put to good use in Asia alongside native and Irish traditions. This will clarify the gaps in his biography – these have been the years of Fenian (Irish republican) violence, of the Molly Maguires, a secret labour society that fought Pinkertons within the Pennsylvania coalfields, of the 1877 normal strike, and of a widespread radical tradition, not least amongst migrant staff.

He grew to become an anticolonial movie star: crowds of hundreds would journey, typically for days, to listen to him converse

From San Francisco, Carroll labored the trans-Pacific ships to Yokohama, and finally grew to become a docker in Rangoon. In 1900, he ordained as a Buddhist monk in a serious ritual celebrated by senior monks, with one other 100 monks and 200 laypeople in attendance, all sponsored by a Chinese language Buddhist. Working within the multi-ethnic areas of crusing and dock work, Dhammaloka claimed to talk seven Asian languages. On the very least, he definitely spoke Hindi-Urdu effectively sufficient to win arguments.

Greater than this, he knew how you can get on with individuals. Like many a sailor, hobo and Irish emigrant, telling tales helped him make new mates and get by way of arduous instances. Residing on his wits, he was fast to make a connection, concerned about different individuals’s lives and worlds, and outraged by the injustices they suffered. When individuals met him, they remembered him – and instructed Dhammaloka tales lengthy after he had handed by way of their lives.

Specifically, Dhammaloka beloved the richness of Asian cultures and sought to defend them towards colonial destruction. In his 14 years as a campaigning monk, he was lively within the nations we now name Sri Lanka, India, Bangladesh, Burma, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Japan, Australia, and maybe additionally China, Nepal and Cambodia. Alongside the way in which, he steadily grew to become an anticolonial movie star: crowds of hundreds would journey, typically for days, to listen to him converse in distant locations in rural Burma or Sri Lanka, a lot in order that legal guidelines could have been modified to cease him. His pamphlets have been printed by the tens or lots of of hundreds, and distributed broadly.

He grew to become immensely standard for his willingness to confront colonial injustices, such because the kidnapping for slave labour of younger boys and girls, or corruption in excessive locations. Colonial officers usually deserted their ‘native wives’ and youngsters after they retired ‘house’ to England: Dhammaloka campaigned towards this so successfully that the viceroy pressured them to legalise such marriages, therefore stopping them from remarrying ‘at house’.

However he was not simply an remoted troublemaker. At each stage he acted because the dramatic ‘entrance man’ for efficient Asian networks of many alternative sorts: Sri Lankan anticolonial Buddhists, Indian radical activists, the diaspora of the Tavoy (Dawei) ethnic minority throughout Burma and Thailand, the Chinese language diaspora in Burma and in Singapore, a Shan chieftain from Burma’s borders, Japanese Buddhist modernisers – and past these, the growing social actions of pan-Asian Buddhist revival and standard self-organising that might finally assist sweep the empire away.

Buddhism performed an important position right here, connecting individuals throughout Asia in very other ways than did European empires. The faith had been born in India and Nepal, then unfold into at present’s Bangladesh, Pakistan, Afghanistan and alongside the Silk Street. It was dominant in British Burma and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and French-ruled Indochina (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia). It performed an vital position in at present’s Malaysia, Singapore, China and, to some extent, Korea.

Of the three Asian nations uncolonised in 1901, Siam (at present’s Thailand) and Tibet have been Buddhist. The rising energy, Japan, shortly to be the primary Asian nation to defeat a European energy within the Russo-Japanese Conflict, counted Buddhism amongst its essential religions, and despatched Buddhist clergy to the remainder of Buddhist Asia and to the diaspora in Hawaii, California and Brazil. Buddhism was older than Christianity and (wrongly) believed to have extra adherents. Along with the empire’s weak spot round faith, this gave Buddhism actual potential as a car for anticolonial motion.

As Dhammaloka stated – repeatedly, loudly and publicly – colonialism got here with ‘the Bible, the whiskey bottle and the Gatling gun’. From this attitude, a sensible programme of difficult missionaries and dealing for temperance adopted. The Gatling gun – army conquest – couldn’t be challenged immediately; however the Irish transfer of difficult colonial faith as a proxy for imperial energy labored effectively.

Greater than this, an Irish Buddhist was a fear for the British Empire, and never solely in Kipling. Irish emigrants labored not solely in factories or as home servants. Some, like Dhammaloka, did work on the ships and docks that held the empire collectively. Lots of the poorest joined the British Military: the rifles pointed at Asian crowds have been usually held in Irish palms. However what in the event that they misplaced their loyalty to the empire, and made frequent trigger with Burmese – or Indian, or Sri Lankan – individuals who have been additionally organising themselves and would possibly as soon as once more revolt towards overseas rule? And what in the event that they transformed to a pan-Asian faith like Buddhism? When Dhammaloka confronted the off-duty policeman on the full moon competition in 1901, these have been a few of the unnerving questions that he delivered to the fore.

Missionary critique of Buddhism was professional, however a monk’s critique of Christianity was sedition

Within the decade that adopted, he was lively throughout Asia on talking excursions, founding colleges, creating organisations, publishing and distributing tracts. The yr 1909 noticed a high-profile tour of Ceylon marked by newspaper polemics, counter-lectures, police surveillance, threats of authorized motion, disrupted conferences – and really giant crowds. In a time of accelerating rigidity throughout the empire – with Gandhi’s boycott motion taking off in India and dealing with extreme repression – colonial authorities could have felt they needed to intervene.

In late 1910, Dhammaloka was charged with sedition within the Burmese city of Moulmein, centred round his problem to ‘the Bible, the whiskey bottle and the Gatling gun’. Complaints about this had been made by two missionaries: one Anglican and the opposite Baptist (the latter shortly to be fined for his mistreatment of inmates within the institute for the blind). The streets have been so stuffed with Dhammaloka’s supporters that his trial was postponed. Ultimately, it was held surrounded by troopers and police. He was convicted: missionary critique of Buddhism was professional, however a monk’s critique of Christianity was sedition.

On Friday 13 January 1911, the streets of Rangoon, too, have been stuffed with a multi-ethnic crowd supporting Dhammaloka in his attraction towards the Moulmein conviction. He was pulled in ceremonial procession by a crowd of laity and Buddhist monks, an honour usually reserved for probably the most senior monks and members of the deposed royal household. It was not solely the ‘Burmese bazaar’ that closed that day. Dhammaloka’s Tavoy monastery – a node for that ethnic diaspora and for poor whites like him – was positioned in Chinatown, the place he had many supporters. The Chinese language and Indian bazaars additionally emptied on to the streets of Rangoon, and even the native cinema (the primary within the nation) donated two days’ takings to the defence fund.

His lawyer was U Chit Hlaing, later a number one nationalist determine, however Dhammaloka’s most strategic supporter was Pranjivan Mehta, a Mumbai-born doctor and shut ally of Gandhi’s. The newspaper Mehta based, United Burma, was seen as deeply subversive by the authorities, however much more threatening was his growing alliance with the Indian Muslim dockworkers who made Rangoon’s actions as a colonial port doable. This multi-ethnic and multi-religious crowd – Burmese, Indian and Chinese language – stood behind Dhammaloka in his confrontation with the British Empire, and prefigured the alliances throughout entrenched ethnic and spiritual divides that problem the Burmese army dictatorship at present.

Confronted with this incipient alliance, the authorities tried to decrease the stakes with out dropping face. Dhammaloka was certain over to maintain the peace: pressured to remain inside the legislation for 12 months on ache of his supporters dropping the bond cash they needed to put up for him. (We found a few of these particulars within the Swedish-language pages of the Minnesota Forskaren, an anarchist newspaper that republished clippings Dhammaloka had despatched to his radical free-thinking allies within the New York journal The Fact Seeker.)

Then, regardless of the multi-ethnic wrestle he had instigated and his rising status, the day after his time period of excellent behaviour ended, Dhammaloka sailed for Australia, by no means to return to Burma. From Melbourne got here a pseudonymous letter asserting his demise, signed with the surname of an Irish labour organiser, and obituaries have been printed all over the world. A number of months later, he reappeared in Singapore, Penang, Ipoh and Bangkok, and claimed to have frolicked in Cambodia. He vanished for good in late 1913 or early 1914.

Despite our greatest efforts and people of collaborators all over the world, we’ve got not been capable of finding out what occurred to Dhammaloka. Maybe he died quietly, someplace distant, with the upcoming world struggle drowning out the information. Possibly he was killed and buried someplace unknown. Or maybe he modified his identify and costume once more, slipping away to steer one other life some place else. We have no idea.

What we do know is that his story offers us an surprising window into the multi-ethnic grassroots that in these a long time reworked anticolonial resistance from a largely elite exercise, led by Western-educated middle-class activists, to the mass standard struggles that might finally result in the tip of empire.

Then, as now, 60 per cent of our species lives in Asia. Asian decolonisation alone is the only largest social change that actions from under have led to prior to now 100 years – making it an vital touchstone for at present, when the query of whether or not local weather justice struggles can overturn the fossil gas capitalism driving us headlong to local weather breakdown is an existential concern throughout the planet. Or, certainly, in an age when the query of what decolonisation would possibly appear like at present, after nationwide independence has did not resolve these issues, and the results of empire and slavery stay on, is a burning concern internationally.

It was far clearer that empire might and must be ended than what would come subsequent

The visions of the long run that Dhammaloka and others in his era had have been naturally formed by their current. In multi-ethnic, multilingual empires held collectively by telegraphs, railways and steamships, at present’s world of impartial nation-states, every outlined round a single dominant ethnicity, was not clearly the wave of the long run – certainly, nostalgia for previous native kingdoms and empires was nonetheless widespread. The imaginative and prescient of a pan-Asian Buddhism didn’t come to go (though we’re aware of pan-Islamisms of assorted sorts). Liberals foresaw a world formed by fashionable science, schooling and rationality. Communists and anarchists had their very own internationalist visions of the long run.

Within the 1910s, it was far clearer that empire might and must be ended than what would come subsequent. This is able to solely actually come into focus within the a long time that adopted, because the struggles of peasants, city staff, ladies, spiritual teams, ethnic minorities and others have been introduced underneath the management of nationally organised elites-in-waiting that tried to make a state in their very own picture. But the struggles of that earlier era laid the groundwork for what got here afterwards. What we do, in our makes an attempt to result in a greater world, is extra foreseeable than the small print of the visions that we think about, of a future that even in a a lot smaller world defied the brightest minds of Asia to conceptualise. It isn’t by writing blueprints however within the concerted efforts to problem the forces of destruction that issues change. This thought can, maybe, assist us calm down a few of our makes an attempt to map out the long run, and encourage us to pay extra consideration to how we work collectively at present to beat the present cycle of disaster.

We are able to additionally see that Asian (and African) decolonisation was not a single homogenous factor. The totally different forces that predominated in several nations meant that China and India, Burma and Vietnam, Tanzania and South Africa inhabited this new form of impartial nation-states in very other ways. So, too, we will think about that inside broad parameters there might be many alternative sorts of ecologically sustainable futures doable.

From my very own work on the lifetime of U Dhammaloka, I’ve drawn a deep respect for Burma’s Civil Disobedience Motion at present and its capability to problem anti-Muslim and anti-Rohingya racism within the Burman Buddhist majority, in addition to to attach many alternative social lessons and ethnicities in a shared problem to the dictatorship. The forces ranged towards them are large and brutal; every day brings information of extra disappearances and killings. And but they don’t surrender, any greater than we should always when confronted with local weather despair or the repression of ecological activism. In any case, they’ve been right here earlier than: in earlier uprisings which have prompted army energy to wobble, in the long run of British rule in Burma, and earlier than, on the streets of Rangoon, 100 years in the past, with this irrepressible, quirky, courageous and memorable Irish Buddhist.