In 1989, Cambridge College Press introduced the publication of a brand new, three-volume ebook series: The Cambridge Translations of Medieval Philosophical Texts. The first quantity – edited by Norman Kretzmann and Eleonore Stump, and devoted to logic and the philosophy of language – contained 15 medieval texts, of which 15 have been composed by Christian authors. The second quantity within the sequence, this time specializing in ethics and political philosophy, appeared in 2000. Seventeen of the 17 texts included on this assortment – edited by Arthur S McGrade, John Kilcullen and Matthew Kempshall – have been authored by Christian writers. Late-medieval Jewish or Islamic texts on ethics or politics? Not in our faculty.

The third quantity of the sequence, this one devoted to thoughts and information, and edited by Robert Pasnau, appeared in 2002. It contained 12 texts, of which 12 have been Christian. No Islamic or Jewish sources made the lower.

Because of the success of the primary three volumes, the press determined to broaden the sequence by two extra, devoted, respectively, to metaphysics and to philosophical theology. It could not be rash to foretell that neither quantity will embody any works by Islamic or Jewish authors. In all probability, a reader of this sequence would get the impression that there merely have been no Islamic or Jewish philosophers in late-medieval occasions (or, a minimum of, no Jewish or Islamic philosophers who wrote on logic, philosophy of language, ethics, politics, or philosophy of thoughts, or whose works deserve any consideration).

However maybe we’re leaping to conclusions. Maybe it was the unavailability of competent translators of medieval philosophical texts in Arabic and Hebrew that accounts for this strict exclusion of such works. If that have been the case, then we’d, after all, want to enquire concerning the causes for the absence of competent translators. However, for all I can inform, the problem of availability of translators from Arabic and Hebrew had nothing to do with the exclusion of Jewish and Islamic works on this sequence. If this omission have been merely a technical matter, it will be straightforward for the editors to accommodate such problem by retitling the sequence ‘The Cambridge Translations of Medieval Christian Philosophical Texts’ (my emphasis). This may appear to be a easy matter of ‘fact in promoting’. And, but, they didn’t make this straightforward qualification.

Why did the editors of The Cambridge Translations of Medieval Philosophical Texts not undertake a title that may specify that the sequence was restricted to Christian texts? Presumably, the specification would make the sequence look rather more parochial – because it certainly is – being a set of anthologies dedicated to a selected spiritual custom. In trying to current the Christian custom as the one recreation on the town in late medieval philosophy, the editors of the sequence apparently thought they have been representing common philosophical discourse (quite than that of a selected spiritual custom), and thus the exclusion of Islamic and Jewish works turned a tool for asserting the universality of Christianity.

An alternate clarification for the exclusion of medieval Islamic and Jewish philosophy is likely to be that the sequence editors have been merely unaware of the exclusionary, distorting and discriminatory nature of their editorial coverage: they could have innocently assumed that medieval philosophy is simply Christian philosophy. Ascribing conceptual blindness of such an unlimited scope to extremely competent students appears to me barely credible, and but we can not completely rule it out since such blindness is certainly a typical mark of exercise dominated by ideology.

Earlier than we talk about what readers of the Cambridge volumes are lacking, let me make one transient statement. Present Anglo-American philosophy is critically (and rightly) engaged with the query of how you can rectify the historic exclusion of varied teams from the philosophical custom. The neglect of medieval Islamic and Jewish philosophy from the historiography of medieval philosophy is barely partly just like the exclusion of different teams, nevertheless. There’s a essential irony to this explicit exclusion. Medieval philosophical tradition, regardless of all its issues, was considerably multicultural; Islamic, Jewish, and Christian authors continuously engaged with one another’s work, typically even collaborating. It is just we, immediately, who’re making a purely Christian narrative that excludes Jewish and Islamic authors from the philosophical discourse.

However what can we, as readers and students, miss out on if we neglect medieval Islamic and Jewish philosophy? I’ll converse to the case of Jewish philosophy, however the identical concepts (although with edifying variations and divergences) apply to Islamic philosophy.

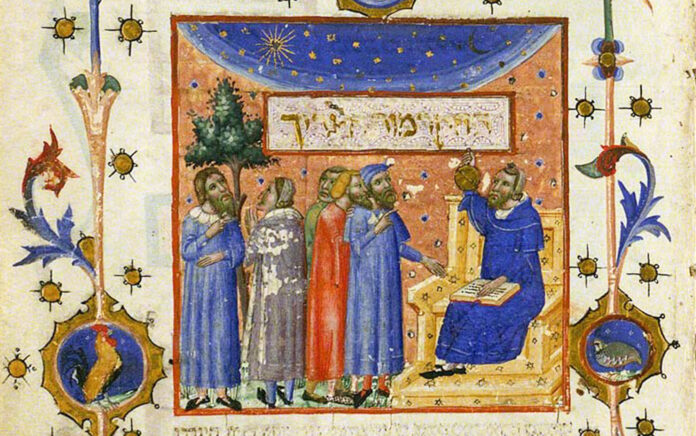

Medieval Jewish philosophy engages with arguments associated to its two essential textual sources: Aristotelian philosophy, and classical Jewish works (the Talmud, midrash, and Scripture). To this point, this characterisation just isn’t that totally different from medieval Christian philosophy. Nonetheless, on a more in-depth look, the variations abound.

Judaism was a small, marginal and dispersed spiritual minority within the Center Ages. These traits performed a task in figuring out the options of its philosophical discourse. Partly resulting from its far-flung social distribution, and partly resulting from its stress on efficiency of spiritual commandments (ie, actions) quite than beliefs, rabbinic Judaism by no means developed a set system of binding dogma. There have been makes an attempt to create such a system – essentially the most well-known of which was Maimonides’s enumeration of his 13 Ideas of Religion – however with out exception such makes an attempt have been colossal failures. In consequence, on many problems with theological and philosophical significance, the views of medieval Jewish philosophers have been in every single place.

Some claimed that God has no bodily options, whereas others seen God as encompassing all of house inside himself (and even as having a physique); some seen God as having no private options in any respect, whereas others ascribed to God emotions, corresponding to remorse, love, and even guilt. Does this number of views mirror a principled dedication to tolerance of variety? Not essentially. A sure diploma of tolerance was required for the sheer survival of Jewish communities: the value of a harsh coverage towards dissent would have been the lack of members of the group and, for such a small group, such a loss can be a heavy value to pay.

Medieval Jewish philosophy was, above all, deeply knowledgeable by the literary persona of a single writer: Moses Maimonides (1135-1204). Maimonides was not solely the best medieval Jewish thinker but additionally one of many best rabbinic authorities of all time. His Mishneh Torah remains to be broadly thought of one of many two most authoritative codifications of Rabbinic legislation. And but, paradoxically, Maimonides was additionally thought of by many Jews to be one of many best heretics of their faith.

Maimonides privileged daring, unorthodox philosophical positions, denying that God has any character

Though Maimonides was fairly loyal to the teachings of Aristotle, he took far bolder positions on theological points. Thus, for instance, in his philosophical masterpiece, the Information of the Perplexed, Maimonides argued that, if unbiased philosophical enquiry led to perception within the eternity of the world, quite than within the Biblical account of creation, one shouldn’t draw back from affirming philosophical fact simply because it conflicts with Scripture. He identified that there are various extra passages in Scripture that ascribe corporeality to God than passages that help creation ex nihilo. Resolutely advocating a radical reinterpretation of all such passages to make them conform to the philosophical view that God is incorporeal, Maimonides claimed that we must always likewise reinterpret all Biblical passages referring to creation to suggest that the world is everlasting, if that was the extra tenable philosophical view.

On a number of key spiritual points, Maimonides additionally privileged daring and unorthodox philosophical positions, denying that God has any character (can a non-person be a lawgiver?), in addition to naturalising the notion of divine windfall (in order that ‘reward’ is simply the pure results of conducting ones’ life rationally and correctly). He deflated the miraculousness of divine miracles, and punctiliously crafted a denial of non-public immortality.

The primary reactions to Maimonides’s claims have been fairly unstable, however his supporters have been additionally quite a few among the many rabbinic strata. And when a few of his opponents introduced a ban on learning philosophy for anybody beneath the age of 25, Maimonides’s proponents responded by saying a counter-ban on those that disallow the research of philosophy. Maimonides’s followers have been quite a few amongst medieval Jewish philosophers and, inside a brief time frame after his loss of life, one can already talk about a Maimonidean college – or quite, colleges – of philosophy, distinguished from one another by the diploma of boldness of their pursuit of the philosophical fact, no matter its settlement with widespread spiritual beliefs and norms.

Benedict de Spinoza (1632-77) and the audacious rationalist thinker Salomon Maimon (1753-1800) have been two of the newest representatives of this college of radical Maimonideanism. Each have been keen to pay a major private value for the sake of sustaining their mental and philosophical integrity. The unconventional Maimonideans weren’t atheists. In actual fact, the very reverse is true: they have been motivated by a real zeal for a real conception of God, a conception that’s free and clear from the broadly prevalent anthropomorphic portrayal of God amongst each the plenty and a major share of the rabbinic elite. On this context, Maimonides himself would often refer derogatorily to ‘Hamon ha-Rabbanim’, actually, the rabbinic multitude, or, if you want, the rabbinic hoi polloi, although his rabbinic {qualifications} have been much more spectacular than the overwhelming majority of those ‘commoners’.

The Janus-faced fame of Maimonides and his thought endured in conflicted attitudes throughout the early trendy interval. Within the 18th century, Rabbi Jacob Emden (the rabbinic guide of Moses Mendelssohn, the chief of the Jewish Enlightenment motion) proposed that maybe there have been two authors named Moses Maimonides, for one couldn’t presumably comprehend how the illustrious writer of the celebrated rabbinic code, the Mishneh Torah, might additionally pen the horrible philosophical assertions discovered within the Information of the Perplexed.

A equally ambivalent response is mirrored in a typical apply amongst early trendy central-European rabbis who wished to check Maimonides’s Information of the Perplexed. A Sixteenth-century doc issued in Prague comprises an in depth checklist of the suspicious, heretical opinions one can discover within the Information. Any rabbinic scholar of the time who wished to check the ebook was required to evaluation this checklist of opinions and to admit, on the one hand, to not consider in any of those heretical opinions whereas, then again, promising to not impute any of them to Maimonides, the nice Talmudist.

Thomas Aquinas’s writings show sustained curiosity within the views of non-Christian writers

In some ways, Maimonides was a Mediterranean thinker, as Sarah Stroumsa places it in her fascinating study. This characterisation is apt not solely by way of his precise biography (he was born in Córdoba, Spain, emigrated to North Africa, then Palestine, and ultimately settled in Fustat, Egypt), nor even by way of his correspondence (which ranged from Provence within the west, to Yemen and Baghdad within the east) however, much more so, by way of the group of philosophers with whom he was conversing. His two favorite philosophers have been Aristotle and al-Farabi (for essentially the most half, Maimonides had little appreciation for his Jewish philosophical predecessors). Certainly, Maimonides bluntly asks his readers to keep away from evaluating views based on our social disposition or our categorisation of the speaker who expresses them. ‘Hear the reality from whoever spoke it’ turned a slogan of this angle of Maimonides. Judging opinions based on their veracity, quite than the social milieu of the speaker, is a advice that’s nonetheless very a lot advisable immediately.

Maimonides was by no means distinctive amongst medieval philosophers in ascribing a lot significance to the philosophical views of thinkers who weren’t his co-religionist. Thomas Aquinas’s writings show sustained curiosity within the views of Maimonides, Avicenna and different non-Christian writers, and Aquinas’s dialogue of those writers is respectful and severe. We should always not disregard the numerous spiritual violence that was not unusual within the later Center Ages. Nonetheless, there’s something fairly spectacular within the method through which medieval Christian, Islamic and Jewish philosophers learn the works of one another, continuously disagreeing, however not that not often additionally taking inspiration from the writing of thinkers belonging to different religions.

Let me return to the riddle of Maimonides. What occurs to a tradition whose best spiritual scholar can also be its best heretic? This query has bothered students of Maimonides, of medieval Jewish philosophy, and of rabbinics for a really very long time, and we’re nonetheless removed from having a satisfying reply to the query. It’s clear, nevertheless, that many commonplace assumptions are all of the sudden referred to as into query by advantage of the centrality of such a thinker. ‘If Maimonides might assert x, why might not I?’

The one technique to embark on such questioning of our assumptions, prompted by previous philosophical perception, is by learning the precise works of the philosophers whose insights transfer us. Many such gems of philosophical knowledge are contained in medieval and early trendy Jewish and Islamic philosophical works. And there are various. However to check this corpus of philosophical literature, we should first acknowledge its very existence. And that is one thing that present-day assumptions concerning the scope and research of philosophy’s previous have lamentably obscured.