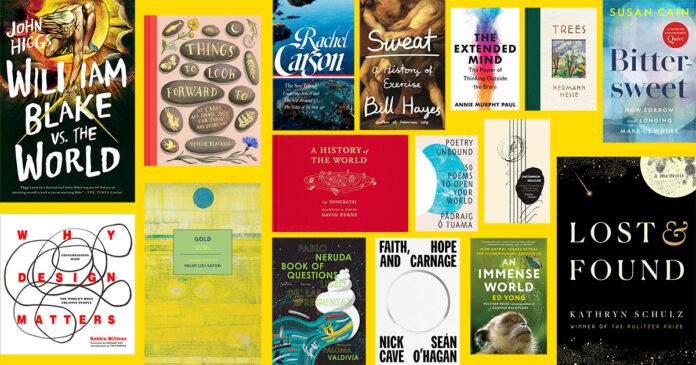

On this sixteenth year of The Marginalian, which attracts totally on the timeless wonders and wisdoms of the previous, listed here are sixteen books of the speedy current that left on me a mark on par with these immortals — books that shimmer with the everlasting and the common, books sure to go on nourishing generations to come back, books that provide succor for the basic problem of reside a harmonious, fulfilling, and wonder-smitten life.

As usual, consider the choice not as a hierarchy however as a bookshelf, organized by an inside logic native to the house and the thoughts wherein the bookshelf is suspended.

JOHN HIGGS: WILLIAM BLAKE VS. THE WORLD

In the course of a London August in 1827, a small group of mourners gathered on a hill within the fields simply north of town limits at Bunhill Fields, named for “bone hill,” longtime burial floor for the disgraceful useless. There, in what was now a dissenters’ cemetery, the English Poor Legal guidelines had ensured a pauper’s funeral for the person who had died 5 days earlier in his squalid residence and was now being lowered into an unmarked grave. The person whose “Songs of Innocence” would light the creative spark within the younger Maurice Sendak’s creativeness a century-some later. The person Patti Smith would rejoice as “the loom’s loom, spinning the fiber of revelation” — a guiding solar within the human cosmos of creativity.

In the course of a London August in 1827, a small group of mourners gathered on a hill within the fields simply north of town limits at Bunhill Fields, named for “bone hill,” longtime burial floor for the disgraceful useless. There, in what was now a dissenters’ cemetery, the English Poor Legal guidelines had ensured a pauper’s funeral for the person who had died 5 days earlier in his squalid residence and was now being lowered into an unmarked grave. The person whose “Songs of Innocence” would light the creative spark within the younger Maurice Sendak’s creativeness a century-some later. The person Patti Smith would rejoice as “the loom’s loom, spinning the fiber of revelation” — a guiding solar within the human cosmos of creativity.

Those that knew William Blake (November 28, 1757–August 12, 1827) cherished his overwhelming kindness, his capability for delight even throughout his frequent and fathomless depressions, his “expression of nice sweetness, however bordering on weak point — besides when his options are animated by expression, after which he has an air of inspiration about him.” He was remembered for the unusual, koan-like issues he mentioned about Jesus (He’s the one God. And so am I and so are you.), in regards to the affluent artists who held his poverty as proof of his failure (I possess my visions and peace. They’ve bartered their birthright for a multitude of pottage.), in regards to the nature of creativity (The tree which strikes some to tears of pleasure is within the eyes of others solely a inexperienced factor which stands in the best way… As a person is, so he sees.)

Unseen by his personal world, he noticed deep into the worlds to come back, channeling his visions via something at hand. It was not the medium that mattered, however its pliancy as he bent it to his imaginative and prescient of the thriller that’s itself the message — the message we name artwork: He was a painter, a poet, a philosopher without meaning to, an early prophet of panpsychism, a mystic who lived to not clear up the thriller however to experience it, to encode it in verses and etch it onto copper plates and stain it onto canvases and seed it into souls for hundreds of years to come back.

As an artist, he was resolutely his personal normal, his personal guiding solar. Like Beethoven, with whom he shared a death-year and the cussed unwillingness to compromise on the inventive imaginative and prescient he skilled as life, Blake was decided to make what he needed to make and to make it on his personal phrases — in a world unready for the artwork and unfriendly to the phrases.

There is no such thing as a larger act of artistic braveness than this.

And so, centuries earlier than the applied sciences existed to allow the proof, William Blake turned the primary dwelling conjecture of the 1,000 True Fans theory. He knew what all of us finally notice, if we’re awake and brave sufficient: that the easiest way — and the one efficient means — to complain about the best way issues are is to make new and higher issues, untested and unexampled issues, issues that spring from the gravity of artistic conviction and drag the established order like a tide towards some new horizon.

How he did that’s what John Higgs explores within the very good biography William Blake vs. the World (public library). Learn extra about and of it here.

ED YONG: AN IMMENSE WORLD

With out shade, life can be a mistake. I imply this each existentially and evolutionarily: Shade is just not solely our major sensorium of magnificence — that aesthetic rapture with out which life can be a desert of the soul — however shade is how we came to exist within the first place. Our notion of shade, like our total perceptual expertise, is a part of our creaturely inheritance and bounded by it — expertise that differs wildly from that of different species, and even varies vastly inside our personal species. In that limitation lies a wonderful invitation to fathom the fundaments of our humanity and step past ourselves into different sensoria extra dazzling than our consciousness is even outfitted to think about.

With out shade, life can be a mistake. I imply this each existentially and evolutionarily: Shade is just not solely our major sensorium of magnificence — that aesthetic rapture with out which life can be a desert of the soul — however shade is how we came to exist within the first place. Our notion of shade, like our total perceptual expertise, is a part of our creaturely inheritance and bounded by it — expertise that differs wildly from that of different species, and even varies vastly inside our personal species. In that limitation lies a wonderful invitation to fathom the fundaments of our humanity and step past ourselves into different sensoria extra dazzling than our consciousness is even outfitted to think about.

That’s the invitation Ed Yong — one of many most insightful science writers of our time, and probably the most soulful — extends in An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us (public library), appropriately titled after a verse by William Blake:

How are you aware however ev’ry Fowl that cuts the ethereal means,

Is an immense world of pleasure, clos’d by your senses 5?

1 / 4 millennium of science after Blake — 1 / 4 millennium of magnifying delight via the lens of data — Yong writes:

Earth teems with sights and textures, sounds and vibrations, smells and tastes, electrical and magnetic fields. However each animal can solely faucet right into a small fraction of actuality’s fullness. Every is enclosed inside its personal distinctive sensory bubble, perceiving however a tiny sliver of an immense world.

With an eye fixed to the Umwelt — that pretty German phrase for the sensory bubble every creature inhabits, each limiting and defining its perceptual actuality — he provides:

Our Umwelt remains to be restricted; it simply doesn’t really feel that means. To us, it feels all-encompassing. It’s all that we all know, and so we simply mistake it for all there may be to know. That is an phantasm, and one that each animal shares.

[…]

Nothing can sense every thing, and nothing must. That’s the reason Umwelten exist in any respect. It’s also why the act of considering the Umwelt of one other creature is so deeply human and so completely profound. Our senses filter in what we’d like. We should select to study the remainder.

We’re insentient to myriad realities available to our fellow creatures — the temperature currents by which a fly, Blake’s supreme existentialist, navigates the air; the ultrasonic calls with which hummingbirds hover between science and magic; the magnetic fields by which nightingales migrate. With the perspectival felicity that science singularly confers, Yong writes:

The Umwelt idea can really feel constrictive as a result of it implies that each creature is trapped inside the home of its senses. However to me, the thought is splendidly expansive. It tells us that every one is just not because it appears and that every thing we expertise is however a filtered model of every thing that we might expertise. It reminds us that there’s gentle in darkness, noise in silence, richness in nothingness. It hints at sparkles of the unfamiliar within the acquainted, of the extraordinary within the on a regular basis, of magnificence in mundanity… After we take note of different animals, our personal world expands and deepens.

Learn extra here.

SOPHIE BLACKALL: THINGS TO LOOK FORWARD TO

“How we spend our days is, after all, how we spend our lives,” Annie Dillard wrote in her timeless meditation on living with presence. “Lay maintain of to-day’s process, and you’ll not have to rely a lot upon to-morrow’s,” Seneca exhorted two millennia earlier as he provided the Stoic balance sheet for time spent, saved, and wasted, reminding us that “nothing is ours, besides time.”

“How we spend our days is, after all, how we spend our lives,” Annie Dillard wrote in her timeless meditation on living with presence. “Lay maintain of to-day’s process, and you’ll not have to rely a lot upon to-morrow’s,” Seneca exhorted two millennia earlier as he provided the Stoic balance sheet for time spent, saved, and wasted, reminding us that “nothing is ours, besides time.”

Time is all we now have as a result of time is what we are — which is why the undoing of time, of time’s promise of itself, is the undoing of our very selves.

Within the dismorrowed undoing of 2020 — as Zadie Smith was calibrating the limitations of Stoic philosophy in a world all of the sudden time-warped by a world quarantine, all of the sudden sobered to the perennial uncertainty of the longer term — loss past the collective heartache besieged the miniature world of my sunny-spirited, largehearted buddy and Caldecott-winning kids’s e book maker Sophie Blackall. She coped the best way all artists cope, complained the best way all makers complain: by making one thing of magnificence and substance, one thing that begins as a quickening of self-salvation in a single’s personal coronary heart and ripples out to the touch, to salve, perhaps even to avoid wasting others — which could be each the broadest and probably the most exact definition of artwork.

One morning below the new bathe, Sophie started making a psychological checklist of issues to look ahead to — a stunning gesture of taking tomorrow’s outstretched hand in that handshake of belief and resolve we name optimism.

Because the checklist grew and she or he started drawing every merchandise on it, she seen what number of had been issues that needn’t await some unsure future — unfussy gladnesses available within the now, any now. A century after Hermann Hesse extolled “the little joys” as a very powerful behavior for totally current dwelling, Sophie’s checklist turned not an emblem of expectancy however an invite to presence — not a deferral of life however a celebration of it, of the myriad marvels that come alive as quickly as we grow to be just a bit extra attentive, slightly extra appreciative, slightly extra animated by our personal elemental nature as “atoms with consciousness” and “matter with curiosity.”

Sophie started sharing the illustrated meditations on her Instagram (which is itself a uncommon island of unremitting delight and generosity amid the stream of hole selfing we name social media) — every half report of non-public gladness, half artistic immediate. Delight begets delight — individuals started sending her their responses to those prompts: unbidden kindnesses carried out for neighbors, surprising hobbies taken up, and oh so many candy unusual faces drawn on eggs.

A slipstream of tomorrows therefore, her checklist turned Things to Look Forward to: 52 Large and Small Joys for Today and Every Day (public library) — a felicitous catalogue partway between Tolstoy’s Calendar of Wisdom and poet Ross Homosexual’s Book of Delights, each web page of it radiant with the heat and marvel that make life price dwelling and mark every thing Sophie makes.

You’ll be able to relish a rainbow and a cup of tea, dawn and a flock of birds, a cemetery stroll and a buddy’s new child, the primary blush of wildflowers in a patch of dust and the looping rapture of an outdated favourite tune. You’ll be able to’t tidy up the White Home, however you may tidy up that uncared for messy nook of your own home; you may’t mend a world, however you may mend the opening within the polka-dot pocket of your favourite coat. They don’t seem to be the identical factor, however they’re a part of the identical factor, which is all there may be — life dwelling itself via us, second by second, one damaged stunning factor at a time.

Learn and see extra here.

SUSAN CAIN: BITTERSWEET

“Oh, there should be slightly little bit of air, slightly little bit of happiness… to let the shape be felt… however let the entire be sombre,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother as he exulted in the beauty of sorrow — not in that wallowing means some have of creating an id of their struggling, not in the best way our tradition has of fetishizing the tortured genius fable, however in the best way of Whitman, who noticed the plain equivalence between feeling deeply all of life’s hues and so touching its magnificence extra deeply, the contact we name artwork: Those that attain “sunny expanses and sky-reaching heights,” Whitman knew, are additionally apt “to dwell on the naked spots and darknesses.” He had “a idea that no artist or work of the very first-class could also be or could be with out them”; his personal life was living proof of that idea. Two millennia earlier than him, Aristotle too had questioned why an undertone of melancholy appears to reverberate throughout the personalities of probably the most fertile minds, the best leaders, and the best artists.

“Oh, there should be slightly little bit of air, slightly little bit of happiness… to let the shape be felt… however let the entire be sombre,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother as he exulted in the beauty of sorrow — not in that wallowing means some have of creating an id of their struggling, not in the best way our tradition has of fetishizing the tortured genius fable, however in the best way of Whitman, who noticed the plain equivalence between feeling deeply all of life’s hues and so touching its magnificence extra deeply, the contact we name artwork: Those that attain “sunny expanses and sky-reaching heights,” Whitman knew, are additionally apt “to dwell on the naked spots and darknesses.” He had “a idea that no artist or work of the very first-class could also be or could be with out them”; his personal life was living proof of that idea. Two millennia earlier than him, Aristotle too had questioned why an undertone of melancholy appears to reverberate throughout the personalities of probably the most fertile minds, the best leaders, and the best artists.

I too have questioned this whereas falling in love with the individuals I reside with — Rachel Carson, together with her unusual grasp of the beauty inside the tragedy of transience; Rockwell Kent, who went to the remotest wilderness to find loneliness as a catalyst of creativity; Beethoven, who turned a lifetime of sorrow into universal joy; Lincoln, who made of his melancholy a source of poetry and power; and Emily Dickinson, who turned the interleaving of love and loss into an everlasting backyard of pleasure.

I believe that beneath all of it is just not an acceptance of however the eager for an acceptance of the basic interaction between darkness and light-weight, magnificence and sorrow, mortality and that means — the longing we transmute into that means, that nice act of creation.

Virginia Woolf known as this the “shock-receiving capacity” essential for being an artist — the willingness to see the totality of life, in all its syncopations of grief and gladness, of magnificence and brutality, and really feel the shock of all of it, and make of that shock one thing that shimmers with that means. Susan Cain calls it “the bittersweet” — “an inclination to states of longing, poignancy, and sorrow; an acute consciousness of passing time; and a curiously piercing pleasure at the great thing about the world.” Whitman and Woolf, Carson and Kent, Lincoln and Dickinson had been all paragons of the bittersweet.

First woke up to it by a curiosity about her personal disproportionate love of music in a minor key, Cain realized that “the music was only a gateway to a deeper realm, the place you discover that the world is sacred and mysterious, enchanted even” — a realm we will enter via music or a stroll in an old-growth forest, via poetry or prayer. She started seeing echoes of this nebulous but surprisingly widespread capability for noticing within the lives of artists and thinkers she admired — Beethoven and Buckminster Fuller, Rumi and Alexander the Nice, however none extra exemplary than the artistic patron saint of her life: Leonard Cohen.

So she gave that taste of the spirit a reputation, then got down to perceive it by following a procession of researchers who research its kaleidoscopic sides throughout neurobiology, psychology, social science.

In Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole (public library), she writes:

The bittersweet is… an genuine and elevating response to the issue of being alive in a deeply flawed but stubbornly stunning world. Most of all, bittersweetness exhibits us how to reply to ache: by acknowledging it, and trying to show it into artwork, the best way the musicians do, or therapeutic, or innovation, or the rest that nourishes the soul. If we don’t remodel our sorrows and longings, we will find yourself inflicting them on others through abuse, domination, neglect. But when we notice that every one people know — or will know — loss and struggling, we will flip towards one another.

There’s on this notion an echo of Oscar Wilde’s stirring prison letter, wherein he resolved to show his struggling into transcendence; an echo of Beethoven’s resolve to “take fate by the throat” as soon as he started dropping his listening to; an echo of Marina Abramovič, who turned a harrowing childhood into raw material for art.

On the coronary heart of all of it is an impressed inquiry into “remodeling ache into creativity, transcendence, and love,” posed with sensitivity to the realities and types of ache we reside with, not all of them simply mutable right into a poem or a portray or a tune.

Learn extra here.

HERMANN HESSE: TREES

“Whoever has discovered hearken to bushes,” Hermann Hesse (July 2, 1877–August 9, 1962) wrote in what stays one of humanity’s most beautiful love letters to trees, “not needs to be a tree. He* needs to be nothing besides what he’s. That’s residence. That’s happiness.”

“Whoever has discovered hearken to bushes,” Hermann Hesse (July 2, 1877–August 9, 1962) wrote in what stays one of humanity’s most beautiful love letters to trees, “not needs to be a tree. He* needs to be nothing besides what he’s. That’s residence. That’s happiness.”

However this century-old basic, half meditation and half manifesto, is way from Hesse’s solely contribution to the reliquary of our species’ tender kinship with bushes — these “slim sentinels” watching over our existence, recalibrating our sense of time, fomenting our richest metaphors and our finest poems, talking deeply to each deep-thinking, deep-feeling particular person and enchanting each noticer (which is the opposite phrase for artist). Timber strew Hesse’s novels and essays, his letters and diaries, his poems and work — all that survives of a life so clearly and mirthfully animated by them, from his Black Forest childhood to the Swiss mountain village of his outdated age.

After the heroism of modifying the first-ever full version of Hesse’s writings writings, scholar Volker Michels has culled the best sylvan musings from this immense physique of labor and curated thirty of Hesse’s personal drawings for example them within the slender gem of a e book Trees: An Anthology of Writings and Paintings (public library).

Learn a few of it, and see some his work, here.

RUMI: GOLD

In his sixty-six years, Rumi (September 30, 1207–December 17, 1273) composed almost sixty-six thousand verses, animated by an ecstatic devotion to dwelling extra totally, loving extra deeply, and transferring via the world with the data that you have to “gamble every thing for love, in case you are a real human being.” He rises from the web page historic and everlasting. Magnetic in his eloquent reverence and his soulful intelligence. Majestic in his whirling silk gown and his defiant disdain for his tradition’s worship of standing. Volcanic with poetry.

In his sixty-six years, Rumi (September 30, 1207–December 17, 1273) composed almost sixty-six thousand verses, animated by an ecstatic devotion to dwelling extra totally, loving extra deeply, and transferring via the world with the data that you have to “gamble every thing for love, in case you are a real human being.” He rises from the web page historic and everlasting. Magnetic in his eloquent reverence and his soulful intelligence. Majestic in his whirling silk gown and his defiant disdain for his tradition’s worship of standing. Volcanic with poetry.

Having mastered the mathematical musicality of the quatrain, he turned a virtuoso of the ghazal with its collection of couplets, every invoking a special poetic picture, every topped with the identical chorus — a form of kinetic sculpture of shock, rapturous with rhythm.

A stunning collection of his poetry, together with some by no means beforehand alive in English, seems in Gold (public library), newly translated and inspirited by poet and musician Haleh Liza Gafori.

Reflecting on the artistic problem of invoking the poetic fact of 1 epoch and tradition into one other, she writes:

The languages of Farsi and English possess fairly completely different poetic assets and habits. In English, it’s unimaginable to breed the wealthy interaction of sound and rhyme (inside in addition to terminal) and the wordplay that characterize and even drive Rumi’s poems. In the meantime, the tropes, abstractions, and hyperbole which might be so plentiful in Persian poetry distinction with the spareness and concreteness attribute of poetry in English, particularly within the fashionable custom. I’ve sought to honor the calls for of up to date American poetry and conjure its music whereas, I hope, carrying over the whirling motion and leaping development of thought and imagery in Rumi’s poetry… I’ve chosen poems that appear to me stunning, significant, and central to Rumi’s imaginative and prescient, poems that I felt I might efficiently translate and that talk to our instances.

What emerges is a testomony to the Nobel-winning Polish poet Wisława Szymborska’s pretty notion of “that rare miracle when a translation stops being a translation and becomes… a second original.”

Hear Haleh Liza Gafori learn one of many best poems within the e book here.

RACHEL CARSON: THE SEA TRILOGY

In the whole sweep of our species historical past, nobody has written extra superbly — or extra in truth — in regards to the sea than the poetic marine biologist and ecology patron saint Rachel Carson (Could 27, 1907–April 14, 1964). Her three masterpieces in regards to the water world — Below the Sea-Wind (which started as her groundbreaking essay Undersea), The Sea Round Us (which occasioned her very good National Book Award acceptance speech), and The Fringe of the Sea (which gave us her beautiful meditation on the ocean and the meaning of life) — are actually collected in a single Library of America quantity: Rachel Carson: The Sea Trilogy (public library), launched by Carson’s modern-day counterpart and kindred spirit Sandra Steingraber.

In the whole sweep of our species historical past, nobody has written extra superbly — or extra in truth — in regards to the sea than the poetic marine biologist and ecology patron saint Rachel Carson (Could 27, 1907–April 14, 1964). Her three masterpieces in regards to the water world — Below the Sea-Wind (which started as her groundbreaking essay Undersea), The Sea Round Us (which occasioned her very good National Book Award acceptance speech), and The Fringe of the Sea (which gave us her beautiful meditation on the ocean and the meaning of life) — are actually collected in a single Library of America quantity: Rachel Carson: The Sea Trilogy (public library), launched by Carson’s modern-day counterpart and kindred spirit Sandra Steingraber.

Animating all three is Carson’s singular lyrical prose in regards to the native poetry of nature:

Considering the teeming lifetime of the shore, we now have an uneasy sense of the communication of some common fact that lies simply past our grasp. What’s the message signaled by the hordes of diatoms, flashing their microscopic lights within the night time sea? What fact is expressed by the legions of the barnacles, whitening the rocks with their habitations, every small creature inside discovering the requirements of its existence within the sweep of the surf? And what’s the that means of so tiny a being because the clear wisp of protoplasm that may be a sea lace, present for some motive inscrutable to us — a motive that calls for its presence by the trillion amid the rocks and weeds of the shore? The that means haunts and ever eludes us, and in its very pursuit we method the final word thriller of Life itself.

KATHRYN SCHULZ: LOST & FOUND

“Fearlessness is what love seeks,” Hannah Arendt wrote in her very good early work on love and loss. “Such fearlessness exists solely within the full calm that may not be shaken by occasions anticipated of the longer term… Therefore the one legitimate tense is the current, the Now.”

“Fearlessness is what love seeks,” Hannah Arendt wrote in her very good early work on love and loss. “Such fearlessness exists solely within the full calm that may not be shaken by occasions anticipated of the longer term… Therefore the one legitimate tense is the current, the Now.”

It’s a good-looking statement, an elemental fact we’d glimpse — and be saved by glimpsing — in these uncommon moments of pure presence that dissolve all too rapidly into what Borges knew to be true of human nature: that time is the substance we are made of.

As creatures manufactured from time, we reside within the current and the previous and the longer term abruptly, frequently shaken by all of the fears and hopes, all of the anxieties and anticipations, which might be the value we pay for our majestic hippocampus — that crowning glory of a consciousness able to referencing its reminiscences and experiences previously, able to projecting its objectives and want into the longer term, able to the bleakest despair and of the brightest desires.

This could be, as Elizabeth Gilbert noticed within the wake of dropping the love of her life, why love and loss have one thing elemental in widespread — every is “a force of energy that cannot be controlled or predicted,” one which “comes and goes by itself schedule… doesn’t obey your plans, or your needs [and] will do no matter it needs to you, at any time when it needs to.”

Out of this arises a fundamental equation we settle for as a perform of life, as an echo of the elemental legal guidelines. We settle for it unwittingly, or wittingly but unwillingly, however it’s an entropic given detached to our assent: We love, then we lose. We lose our family members — to loss of life or the dissolution of mutuality — or we lose ourselves. (That is additionally why flowers move us so.)

But when we’re fortunate sufficient, if we’re are cussed sufficient, we love and we lose after which the loss opens us as much as extra love — completely different love, as a result of every love is unrepeatable and irreplaceable — on the opposite aspect of grief; love unimaginable from the barren landmass of loss, love with out which, as soon as discovered, the world involves really feel unimaginable.

As a result of these are the 2 most all-consuming and all-pervading of human experiences, the labels wherein we attempt to classify and comprise them are sure to be too small — as with love, so with loss. (That is what Joan Didion captured in her basic statement that “grief, when it comes, is nothing like we expect it to be.”)

All of this, with all of its subtleties, comes alive on the pages of Lost & Found (public library) by Kathryn Schulz — half private memoir, half existential inquiry into the 2 nice universals of human life.

Learn extra here.

DAVID BYRNE: A HISTORY OF THE WORLD (IN DINGBATS)

“Magnificence is fact, fact magnificence, — that’s all ye know on earth, and all ye have to know,” Keats wrote within the closing strains of his “Ode to a Grecian Urn” within the spring of 1819, within the spring of contemporary science. Humanity was coming abloom with new data of actuality as astronomy was supplanting the superstitions of astrology and chemistry was rising type the primordial waters of alchemy. Ten years earlier, when Keats was an adolescent, Dalton had eventually confirmed the existence of the atom — the nice dream Democritus had dreamt civilizations earlier; the dream Aristotle, drunk on energy and certitude, had squashed along with his idea of the 4 parts. A phenomenal fact buried in a Grecian urn and laid to relaxation, roused two thousand years later by the kiss of chemistry.

“Magnificence is fact, fact magnificence, — that’s all ye know on earth, and all ye have to know,” Keats wrote within the closing strains of his “Ode to a Grecian Urn” within the spring of 1819, within the spring of contemporary science. Humanity was coming abloom with new data of actuality as astronomy was supplanting the superstitions of astrology and chemistry was rising type the primordial waters of alchemy. Ten years earlier, when Keats was an adolescent, Dalton had eventually confirmed the existence of the atom — the nice dream Democritus had dreamt civilizations earlier; the dream Aristotle, drunk on energy and certitude, had squashed along with his idea of the 4 parts. A phenomenal fact buried in a Grecian urn and laid to relaxation, roused two thousand years later by the kiss of chemistry.

The story of our species is punctuated with a thousand analogous atoms of expertise. Fact is magnificence within the workings of the world, however within the workings of humanity, fact is usually sleeping magnificence. Even on the miniature timescale of our personal lifetimes — these grunts within the story of the world — it could take us years or a long time of hindsighted reflection to reach on the fact of our expertise, any expertise, and all of the extra so the larger its complexity and its toll on us.

200 springtimes after Keats, David Byrne explores this side of the human situation in his felicitously uncategorizable e book A History of the World (in Dingbats) (public library) — a playful but poignant meditation, in phrases and drawings, on the human truths unveiled because the world got here unworlded by the worldwide pandemic that turned the nice shared expertise of our lifetimes.

Radiating from the pages, delightfully designed and typeset by Alex Kalman, is Byrne’s buoyant imaginative and prescient for the brand new world, a world of magnified mutuality and widespread poetry of chance; a imaginative and prescient for all times not merely restored to the way it was once however reset, recalibrated, revitalized — life that may be a little bit extra alive.

See extra here.

ANNIE MURPHY PAUL: THE EXTENDED MIND

“Our minds are all threaded collectively,” the younger Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary on the daybreak of the 20th century, “and all of the world is thoughts.” In the meantime in Spain, the middle-aged Santiago Ramón y Cajal was birthing a new science that may each enormously increase our data of the mind and enormously contract our understanding of the thoughts. Over the next half-century, in its noble effort to render understandable what William James so poetically termed the “blooming and buzzing confusion” of consciousness, neuroscience would grow to be each a fantastic leap ahead and a fantastic leap again. Repeatedly, its illuminating however incomplete findings can be aggrandized and oversimplified right into a form of neo-phrenology that incarcerates a few of our most expansive human experiences and capacities — love and grief, intelligence and creativeness — particularly mind areas with explicit neural firing patterns.

“Our minds are all threaded collectively,” the younger Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary on the daybreak of the 20th century, “and all of the world is thoughts.” In the meantime in Spain, the middle-aged Santiago Ramón y Cajal was birthing a new science that may each enormously increase our data of the mind and enormously contract our understanding of the thoughts. Over the next half-century, in its noble effort to render understandable what William James so poetically termed the “blooming and buzzing confusion” of consciousness, neuroscience would grow to be each a fantastic leap ahead and a fantastic leap again. Repeatedly, its illuminating however incomplete findings can be aggrandized and oversimplified right into a form of neo-phrenology that incarcerates a few of our most expansive human experiences and capacities — love and grief, intelligence and creativeness — particularly mind areas with explicit neural firing patterns.

A century later and half a millennium after Descartes cleaved Western consciousness into its disembodied dualism, we’re solely simply starting to reckon with the rising understanding that consciousness is a full-body phenomenon, maybe even a beyond-body phenomenon.

In The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain (public library), Annie Murphy Paul explores probably the most thrilling frontiers of this rising understanding, fusing a century of scientific research with millennia of first-hand expertise from the lives and letters of nice artists, scientists, inventors, and entrepreneurs. Difficult our cultural inheritance of considering that considering takes place solely contained in the mind, she illuminates the myriad methods wherein we “use the world to suppose” — from the sensemaking language of gestures that we purchase as infants lengthy earlier than we will communicate ideas to the singular gasoline that point in nature supplies for the mind’s strongest associative community.

Paul distills this recalibration of understanding:

Pondering exterior the mind means skillfully partaking entities exterior to our heads — the emotions and actions of our our bodies, the bodily areas wherein we study and work, and the minds of the opposite individuals round us — drawing them into our personal psychological processes. By reaching past the mind to recruit these “extra-neural” assets, we’re capable of focus extra intently, comprehend extra deeply, and create extra imaginatively — to entertain concepts that may be actually unthinkable by the mind alone.

Learn extra here.

DEBBIE MILLMAN: WHY DESIGN MATTERS

If we’re not at the least slightly abashed by the individuals we was once, the voyage of life has halted within the windless bay of complacency. This renders the interview a curious cultural artifact by design — a consensual homily of future abashment, etching into the widespread report who we had been at a selected level in life, in a selected state of being, with all of the non permanent totality of ideas and emotions that we so usually mistake for remaining locations of personhood. An interview petrifies us in time, then lives on ceaselessly, the ideas of bygone selves quoted again to us throughout the eons of our private evolution — an odd and discomposing taxidermy diorama of life that’s not dwelling.

If we’re not at the least slightly abashed by the individuals we was once, the voyage of life has halted within the windless bay of complacency. This renders the interview a curious cultural artifact by design — a consensual homily of future abashment, etching into the widespread report who we had been at a selected level in life, in a selected state of being, with all of the non permanent totality of ideas and emotions that we so usually mistake for remaining locations of personhood. An interview petrifies us in time, then lives on ceaselessly, the ideas of bygone selves quoted again to us throughout the eons of our private evolution — an odd and discomposing taxidermy diorama of life that’s not dwelling.

However a fantastic interview does one thing else, too. An excellent touches the nucleus of being and potential, untouched by the forces of time and alter.

One January afternoon a number of selves in the past, I entered the corrugated black partitions of a comfortable recording studio on the Faculty of Visible Arts to sit down at a microphone throughout from a lady dressed totally and impeccably in black — a lady all stranger, all sunshine. I didn’t anticipate that, over the following hour, the heat of her beneficiant curiosity and her delicate consideration would soften away my abnormal reticence about discussing the life beneath the work. I didn’t anticipate that, over the following decade, we’d grow to be artistic kindred spirits, then pals, then longtime romantic companions, and at last expensive lifelong pals and frequent collaborators.

Through the years, I’ve witnessed Debbie interview a kaleidoscope of visionaries — artists, writers, designers, scientists, musicians, philosophers, poets. Each time, friends go away the studio with that particular glow of feeling deeply understood and appreciated, slightly bit extra in contact with ourselves past our selves, reminded of who and what we’re within the hull of our being, in that place from which we make every thing we make as we go on making ourselves. Within the almost twenty years because the delivery of Design Matters — born in that primordial epoch earlier than podcasts, when Debbie really needed to pay for the radio waves transmitting these conversations — she has interviewed greater than 450 artistic individuals in regards to the arc of their lives. Roxane Homosexual — as soon as her interview topic, now her spouse — describes the ensuing totality as “a gloriously attention-grabbing and ongoing dialog about what it means to reside effectively, overcome trauma, face rejection, study to like and be liked, and thrive each personally and professionally.”

One of the best elements of one of the best interviews from this immense physique of labor are actually gathered in Why Design Matters: Conversations with the World’s Most Creative People (public library). Pulsating via them are a handful of widespread themes — the elementary particles of which any artistic life, any lifetime of ardour and function, any totally human life is constructed — none looming bigger than the connection between vulnerability and belonging, which constellates our total cosmos of being: what we make, how we love, why we lengthy for the issues we lengthy for, in love and in work.

Learn a few of the highlights here.

NICK CAVE: FAITH, HOPE AND CARNAGE

The world reveals itself via our engagement with it — a fact as true within the “It for Bit” sense of physics because it within the Dzogchen sense of Tibetan Buddhism.

The world reveals itself via our engagement with it — a fact as true within the “It for Bit” sense of physics because it within the Dzogchen sense of Tibetan Buddhism.

It’s the elementary fact of our human expertise.

All cynicism is a denial of it.

All hope is a tribute to it.

This consciousness pulsates all through Faith, Hope and Carnage (public library) — Nick Cave’s yearlong dialog with journalist turned buddy Seán O’Hagan.

Twenty years after Rebecca Solnit’s epochal Hope in the Dark, with its lucid and luminous case for our grounds against despair, Cave — who has long championed the generative value of hope — displays:

I’ve no time for cynicism. It feels massively misplaced right now.

[…]

I stay cautiously optimistic. I feel if we will transfer past the nervousness and dread and despair, there’s a promise of one thing shifting not simply culturally, however spiritually, too. I really feel that potential within the air, or perhaps a form of subterranean undertow of concern and connectivity, a radical and collective transfer in the direction of a extra empathetic and enhanced existence… It does appear doable — even in opposition to the prison incompetence of our governments, the planet’s ailing well being, the divisiveness that exists in all places, the surprising lack of mercy and forgiveness, the place so many individuals appear to harbour such an irreparable animosity in the direction of the world and one another — even nonetheless, I’ve hope. Collective grief can carry extraordinary change, a form of conversion of the spirit, and with it a fantastic alternative. We will seize this chance, or we will squander it and let it move us by. I hope it’s the former. I really feel there’s a readiness for that, regardless of what we’re led to imagine.

Having lengthy reckoned with the relationship between cynicism and hope, I usually say that cynics — who’re the individuals most deserving of our pity — are simply brokenhearted optimists. There’s each a stunning confluence and a stunning inversion of those concepts in Nick Cave’s assertion that “hope is optimism with a damaged coronary heart,” which appears to me extra like an aphoristic spear nobly thrown at our perpetual tangle of semantics in attempting to distinguish between optimism and hope than a real and helpful definition. However, after all, we every arrive at these notions so trapped in our personal frames of reference, so saturated with our subjective expertise, that no two portraits of a psychological state or emotional orientation might ever probably be exactly alike.

What is for certain is that it doesn’t matter what we name this openhearted craving for betterment, pulsating beneath it’s the infinite vulnerability of remaining unmet — all daring is ceaselessly haunted by the specter of crushing disappointment, and there may be nothing extra daring than a attain from the true to the perfect.

And but this craving springs from our most elementary nature. Residing with it and dwelling as much as it’s the highest homage we will pay, and should pay, to the unbidden present of life.

With an eye fixed to “the mandatory and pressing want to like life and each other, regardless of the informal cruelty of the world,” Cave observes:

In a means my work has grow to be an specific rejection of cynicism and negativity. I merely don’t have any time for it. I imply that fairly actually, and from a private perspective. No time for censure or relentless condemnation. No time for the entire cycle of perpetual blame. Others can try this form of factor. I haven’t the abdomen for it, or the time. Life is just too rattling quick, in my view, to not be awed.

In my very own expertise, nothing seeds cynicism extra readily than the withholding of forgiveness — forgiveness of others, of the world, of Father Likelihood and Mom Circumstance; above all, of oneself. Self-forgiveness is certainly probably the most potent antidote to cynicism I do know.

Cave shines a sidewise gleam on the identical intimation. Half a century after the nice humanistic thinker and psychologist Erich Fromm made his countercultural case for why self-love is the foundation of a sane society, he turns to artwork because the supreme instrument of self-forgiveness:

All of us have regrets and most of us know that these regrets, as excruciating as they are often, are the issues that assist us lead improved lives. Or, relatively, there are specific regrets that, as they emerge, can accompany us on the incremental bettering of our lives. Regrets are ceaselessly floating to the floor… They require our consideration. It’s a must to do one thing with them. A technique is to hunt forgiveness by making what could be known as dwelling amends, through the use of no matter presents you’ll have in an effort to assist rehabilitate the world.

For many people, our artistic contribution — our artwork, to make use of the time period in Baldwin’s broadest sense — is the present we provide to rehabilitate the world and, within the course of, rehabilitate ourselves. Cave displays on his personal expertise of creating music whereas dwelling with the incomprehensible loss of his teenage son and its attendant vortex of self-blame:

Artwork does have the power to avoid wasting us, in so many various methods. It may possibly act as some extent of salvation, as a result of it has the potential to place magnificence again into the world. And that in itself is a means of creating amends, of reconciling us with the world. Artwork has the ability to redress the stability of issues, of our wrongs, of our sins… By “sins,” I imply these acts which might be an offence to God or, in the event you would like, the “good in us” — that reside inside us, and that if we pay them no heed, harden and grow to be a part of our character. They’re types of struggling that may weigh us down terribly and separate us from the world. I’ve discovered that the goodness of the work can go a way in the direction of mitigating them.

PABLO NERUDA: BOOK OF QUESTIONS

“To lose the urge for food for that means we name considering and stop to ask unanswerable questions,” Hannah Arendt wrote in her superb meditation on the life of the mind, would imply to “lose not solely the power to provide these thought-things that we name artworks but in addition the capability to ask all of the answerable questions upon which each and every civilization is based.”

“To lose the urge for food for that means we name considering and stop to ask unanswerable questions,” Hannah Arendt wrote in her superb meditation on the life of the mind, would imply to “lose not solely the power to provide these thought-things that we name artworks but in addition the capability to ask all of the answerable questions upon which each and every civilization is based.”

However our questions, moreover having the ability to civilize us, even have the ability — maybe much more wanted in the present day — to rewild us.

Typically, our deepest questions are our easiest ones, and our wildest questions — probably the most maddeningly unanswerable ones — are our most resaning, most redolent with that means. That is why kids’s questions are so usually portals to the profoundest answers.

Pablo Neruda (July 12, 1904–September 23, 1973) channeled 320 such questions — questions earthly and cosmic about artwork and life, desires and loss of life, nature and human nature; magical-realist questions that would have been requested by a toddler or a sage — into his remaining work of poetry, initially printed months earlier than his sudden loss of life.

His Book of Questions (public library) now comes alive in a shocking bilingual picture-book, illustrated by Chilean artist Paloma Valdivia, whose father grew up in the identical coastal area that formed Neruda’s boyhood and whose grandmother was pals with Neruda’s sister.

Of Neruda’s unique questions — every of them unanswerable, all of them price asking, crackling with some very important spark of playfulness or poignancy — seventy come ablaze amid the colourful illustrations and fold-out delights, radiant with the colours and textures of Latin American tapestry.

Learn and see extra here.

BILL HAYES: SWEAT

“And if the physique weren’t the soul, what’s the soul?” questioned Whitman two years earlier than he wrote a guide on “manly well being and coaching” and twenty years earlier than he recovered from his paralytic stroke with a rigorous exercise regimen within the gymnasium of the wilderness.

“And if the physique weren’t the soul, what’s the soul?” questioned Whitman two years earlier than he wrote a guide on “manly well being and coaching” and twenty years earlier than he recovered from his paralytic stroke with a rigorous exercise regimen within the gymnasium of the wilderness.

However this pure equivalence, as apparent because it was to Whitman and as evident because the neurophysiology of consciousness is making it in our personal epoch — was opaque, even obscene, for a lot of human historical past.

The world’s first recognized e book on train was written nearly precisely two millennia in the past, someday within the 220s, by the Greek thinker and instructor Flavius Philostratus, then in his fifties. In On Gymnastics, he argued that athletic coaching is an artwork and “a type of knowledge,” on par with the opposite arts, no much less stunning or substantive than poetry or music. His treatise was partially an act of resistance to the wave of oppression and erasure sweeping in with the brand new regime of Roman rule and the arrival of Christianity, which was starting to eradicate the traditional Greek tradition of Olympic Video games and informal athletics, of public bathhouses and gymnasia.

Below Christian doctrine, the physique was too sinful an instrument to be afforded public celebration or non-public homilies. The cerebral solemnity of the cathedral changed the joyful physicality of the gymnasium, the place crowds had as soon as gathered as a lot to tone their our bodies as to hone their minds on Plato and Aristotle’s philosophy lectures. (The one place the place Christianity and historic Greek tradition converged was that girls weren’t permitted to compete within the Olympic Video games or enter the gymnasium — regardless that the athletic Plato, outlining the legal guidelines of civilization in his final and longest dialogue, decreed that “ladies, each younger and outdated, ought to train… along with the lads” — and, to today, ladies usually are not permitted to sing within the Vatican choir or maintain main management positions within the Catholic Church.)

And so it’s that the notion of train fell out of the favored creativeness for a millennium. The phrase itself didn’t enter the English language till the fourteenth century, when it was initially used within the context of animal farming and husbandry, that means “to take away restraint.” Like the etymological evolution of “to lose,” “to train” got here to embody different contexts past the literal and the bodily: one might train restraint, or altruism, or warning. However not one’s physique — not but.

After which, within the sixteenth century, whereas roaming the ruins of Greek and Roman gymnasia, an Italian doctor named Girolamo Mercuriale (September 30, 1530–November 8, 1606) took it upon himself “to revive to the sunshine the artwork of train, as soon as so extremely esteemed, and now plunged into deepest obscurity and completely perished.” Far forward of his time on each the size of a lifetime and the size of civilization, Mercuriale was solely twenty-two when, writing a treatise on parenting, he made a passionate case in opposition to the prevalent use of moist nurses, insisting as an alternative that breastfeeding by moms made for more healthy and happier kids. His work impressed the world’s first formal proposal for bodily schooling in class curricula, made by the English educator on whom Shakespeare modeled the schoolmaster in Love’s Labor Misplaced.

However Mercuriale’s most lasting legacy was the 1573 e book De Arte Gymnastica, or The Artwork of Train. (By the way, in my native Bulgarian, the tutorial time period for gymnasium class interprets verbatim to “bodily artwork.”) On its pages — writing in an elaborate type of medieval Latin that solely a handful of students can translate in the present day — Mercuriale resolved:

I’ve taken as my province to revive to the sunshine the artwork of train, as soon as so extremely esteemed, and now plunged into deepest obscurity and completely perished… Why nobody else has taken this on, I dare not say. I do know solely that it is a process of each most utility and massive labor.

If there may be one particular person within the fashionable world who can reinvigorate Mercuriale’s huge unfinished labor and bridge the bodily, the philosophical, and the poetic — bridge Whitman and Warhol, Plato and Peloton, Kafka and Curie, Tennessee Williams and Serena Williams; bridge the “speedy bodily now” of train with “the knowledge of the previous that had pale from dwelling reminiscence” — it’s Invoice Hayes. And so he does, in Sweat: A History of Exercise (public library) — an expedition, each existential and historic, spanning two thousand years and three continents, exploring “how the humanities of train had been invented, misplaced, and rediscovered,” elevating questions on what distinguishes train from apply, labor, or sports activities; about whether or not, like artwork types and literary genres and languages, there are “sure types of train which might be equally endangered or have already gone extinct — unrecorded, undescribed”; questions like:

Do you select your type of train, or does it select you?

Learn extra here.

NATALIE HODGES: UNCOMMON MEASURE

In her 1942 e book Philosophy in a New Key, the trailblazing thinker Susanne Langer outlined music as “a laboratory for feeling and time.” However maybe it’s the reverse, too — music would be the most stunning experiment performed within the laboratory of time.

In her 1942 e book Philosophy in a New Key, the trailblazing thinker Susanne Langer outlined music as “a laboratory for feeling and time.” However maybe it’s the reverse, too — music would be the most stunning experiment performed within the laboratory of time.

In “the wordless beginning,” spacetime itself was crumpled and compacted into that spitball of everythingness we name the singularity. Even when sound might exist then — it didn’t, after all, as a result of sound is made of matter — it could have existed abruptly. Infinite numbers of each doable notice would have been ringing on the identical time — the antithesis of music. It is just as a result of this single level of totality was stretched right into a line that time was born and, all of the sudden, there was continuity. All of the sudden, one second turned distinguishable from one other — the strange gift of entropy, which makes it doable to have melody and rhythm, chords and harmonies.

Music — with all of the mysterious energy by which it “enters one’s ears and dives straight into one’s soul, one’s emotional center” — is made not of notes of sound however of atoms of time. And if music is manufactured from time, and if time is the substance we ourselves are made of, then in some profound sense, we’re manufactured from music.

That — the physics and neuroscience of it, the poetry and unremitting marvel of it — is what the science-enchanted classical violinist Natalie Hodges explores in Uncommon Measure: A Journey Through Music, Performance, and the Science of Time (public library). She writes:

Music sculpts time. Certainly, it’s a structuring of time, as a layered association of audible temporal occasions. Rhythm is on the coronary heart of that association, on each scale: the biking and patterning of repeated sound or motion and the “measured circulation” that that repetition creates. Probably the most elementary rhythm is the beat itself, the heart beat that happens at common intervals and thus dictates the tempo, retains musical time. In music, a beat is not any fastened factor — it could quicken into smaller intervals (accelerando) and stretch out into longer ones (decelerando), relying on the character of a given musical second and the sensation or fancy of the performer — nevertheless it does stay periodic, predictable, inexorable. Even on the degree of pitch, which is actually the velocity of a given sound wave’s oscillation, we’re actually listening to the rhythmic demarcation of time, a tiny coronary heart whirring at a beat of x cycles per second.

But in every bit of music there are additionally increased temporal constructions at play. Repetition begets sample, and sample engenders type, at each scale; thus musical type itself constitutes a macro-rhythm, a sample of alternations that transfer the listener via time.

Our minds construction time via the detection of patterns and the predictive anticipation of recurring parts. However though this cognitive perform unfolds unconsciously, it isn’t mechanistic, not robotic, however an important pulse-beat of our humanity, vibrating with the neural harmonics of emotion, suffused with feeling — for all anticipation is a type of hope and all hope could be shattered or redeemed, taking our hearts together with it. Ever since Pythagoras revolutionized the mathematical construction of music by composing the world’s first algorithm, musicians have been intentionally breaking the buildup of patterns or triumphantly finishing them in an effort to orchestrate an emotional response — the sorrow of unmet hope, the elated reduction of its redemption.

With an eye fixed to the essential chord development, rooted in a tonic, and the satisfying decision of a rondo, revolving round a round theme, Hodges writes:

Such patterns, formal and harmonic, relate their parts to at least one one other in time. The ear can sense the harmonies to come back primarily based on the relative intensities of those who got here earlier than, or when thematic materials will return by the buildup of a cadence on the finish of a growth part or variation. It’s via this increased sense of rhythm, then, {that a} easy phrase or a posh type turns into a temporal object: time molded in an effort to manipulate emotion, placing you thru the modifications of the current solely to carry you again to the previous, finding you in a second that’s concurrently acquainted and wholly new.

In my native Bulgaria, the tonal custom rests upon a sample dramatically completely different from that of Western music and its twelve-tone scale. (That is why a Bulgarian folk song was encoded among the many handful of sounds representing Earth on the Golden Record that sailed aboard the Voyager in humanity’s most poetic attain for making contact with the cosmos.) However whereas these underlying constructions differ throughout cultures and epochs, music’s reliance on such patterns for its emotional impact is common. Hodges observes:

The music of all cultures, every with its personal distinctive guidelines to be adopted and damaged, each weaves and rends the tapestry of audible time. Our expertise of musical temporality, like our expertise of the day-to-day, consists of patterns of recurrence and, in the end, their violation.

But musical time differs from the quotidian passage of abnormal time, even because it exists inside that passage. Or, at the least, it manifests how prone time is to our acutely aware notion, as a lot as the opposite means round.

PÁDRAIG Ó TUAMA: POETRY UNBOUND

Within the dawning hour of the pandemic, Irish poet and peace activist Pádraig Ó Tuama launched the soul-slaking podcast Poetry Unbound, a part of the On Being Project. Two years and several other million listeners later, it now has an equally soul-slaking e book companion in Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World (public library) — a vitalizing exploration of and invitation into poetry as protest, poetry as sacrament, poetry as exorcism, poetry as an instrument of deepening the truths we will inform one another, the truths we will see in and for ourselves, poetry as a reminder that these truths are of dazzling multiplicity and simultaneity, usually in artistic rigidity with one another, a rigidity that expands and magnifies our being; poetry as “a lonely artwork, written by an individual with a way that extra should be carried out.”

Within the dawning hour of the pandemic, Irish poet and peace activist Pádraig Ó Tuama launched the soul-slaking podcast Poetry Unbound, a part of the On Being Project. Two years and several other million listeners later, it now has an equally soul-slaking e book companion in Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World (public library) — a vitalizing exploration of and invitation into poetry as protest, poetry as sacrament, poetry as exorcism, poetry as an instrument of deepening the truths we will inform one another, the truths we will see in and for ourselves, poetry as a reminder that these truths are of dazzling multiplicity and simultaneity, usually in artistic rigidity with one another, a rigidity that expands and magnifies our being; poetry as “a lonely artwork, written by an individual with a way that extra should be carried out.”

Rising from these pages above all is poetry as prayerful consideration to life, captured within the completely chosen epigraph from poet Christian Wiman:

Ultimately we go to poetry for one motive, in order that we’d extra totally inhabit our lives and the world wherein we reside them, and that if we extra totally inhabit these items, we could be much less apt to destroy each.

Echoing Emerson’s statement that “our music, our poetry, our language itself usually are not satisfactions, however solutions,” Ó Tuama writes within the introduction:

A single second can open a door to an expertise that’s larger than the only second may indicate. Typically that opening is a problem, generally it’s a consolation, different instances a query. Very sometimes it’s a solution.

[…]

A poem could be like a flame: serving to us discover our means, preserving us heat.

These moments are available in many shapes, from poems of infinite selection. In a single, a single phrase turns into “a solitary phrase, a phrase of arrival, a phrase of presence.” In one other, the central picture turns into “an exploration of what it means to be wished effectively by another person.” Collectively, they grow to be “a testomony to the method of noticing” — one thing delicate and mighty that reveals “what can occur after we take note of our lives.”

For extra timeless favorites, revisit the alternatives for 2021, 2020, 2019, and beyond.