There’s a phenomenon in forests often known as inosculation — the fusing collectively of separate timber right into a single organism after their branches or roots have been entwined for a very long time. Generally, one of many former people could also be minimize or damaged on the base, nevertheless it stays totally alive by means of its sinewy fusion with the previous different. That is not symbiosis between two distinct organisms however a hybrid new organism totally sharing within the sources of life.

Every thing alive has the potential for inosculation in a single type or one other. That, maybe, is what the nice naturalist John Muir meant when he noticed that when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” To be correct residents of that universe is to acknowledge ourselves as particles of it, indelibly linked to each different particle — particles every minuscule however majestic with risk; it’s to acknowledge that, as Dr. King noticed, “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality.”

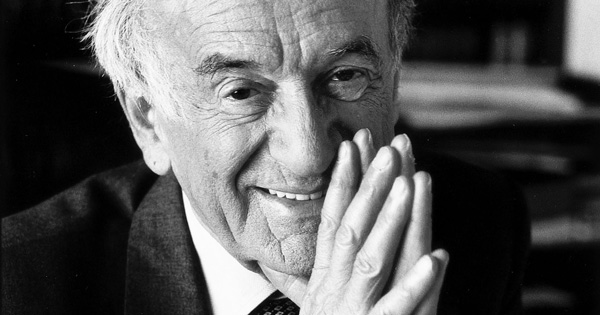

Few have captured the duty and energy of that mutuality extra passionately, nor lived them extra totally, than Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel (September 30, 1928–July 2, 2016).

In Conversations with Elie Wiesel (public library), the Biblical query Cain poses to God after killing Abel — “Am I my brother’s keeper?” — turns into a lens on what makes for brotherhood within the broadest humanistic sense. Wiesel displays:

We’re all our brothers’ keepers… Both we see in one another brothers, or we stay in a world of strangers… There aren’t any strangers in a world that turns into smaller and smaller. As we speak I do know straight away when one thing occurs, no matter occurs, anyplace on the planet. So there is no such thing as a excuse for us to not be concerned in these issues. A century in the past, by the point the information of a battle reached one other place, the battle was over. Now individuals die and the images of their dying are supplied to you and to me whereas we’re having dinner. Since I do know, how can I not rework that data into duty? So the important thing phrase is “duty.” Meaning I have to preserve my brother.

Every time we quiet the voices of so-called civilization — the voices of selfing and hard-edged individualism — that sense of the interconnectedness of life and of lives turns into audible. And but we’re habitually deafened to it by a sort of desensitization — the type the poet Could Sarton so poignantly captured as she contemplated how to live with tenderness in a harsh world. A lot of it, Wiesel observes, is a type of paralysis that comes from the sheer mismatch between the size of the issues the world hurls at us and our particular person locus of company — a selected pathology of the knowledge age, additional exploited by the information media and their crisis-mongering. Wiesel considers the consequence:

We’re careless. In some way life has been cheapened in our personal eyes. The sanctity of life, the sacred dimension of each minute of human existence, is gone. The primary drawback is that there are such a lot of conditions that demand our consideration. There are such a lot of tragedies that want our involvement. The place do you start?

With an eye fixed to a central drawback of our time — how to live with wisdom in the age of information — he provides:

We all know an excessive amount of. No, let me appropriate myself. We’re knowledgeable about too many issues. Whether or not data is reworked into data is a distinct story, a distinct query.

He traces the emotional attrition that occurs once we are bombarded with information of crises and traumatic occasions — at first deeply moved and invested in allaying the struggling we see, we develop exhausted by trauma-sighting and help-canvassing, simply as information of the newest calamity or injustice is piling atop the earlier one:

You couldn’t take it. There’s a want to recollect, and it could final solely a day or per week at a time. We can not keep in mind on a regular basis. That may be not possible; we’d be numb. If I had been to recollect on a regular basis, I wouldn’t be capable to perform. An individual who’s delicate, at all times responding, at all times listening, at all times able to obtain another person’s ache… how can one stay?

The antidote to this paralysis, Wiesel argues, is small motion — a testomony to Hannah Arendt’s conviction that “the smallest act in the most limited circumstances bears the seed of… boundlessness, because one deed, and sometimes one word, suffices to change every constellation.” A century and a half after Van Gogh insisted that “however meaningless and vain, however dead life appears, the man of faith, of energy, of warmth… steps in and does something,” Wiesel insists on selecting from among the many innumerable causes soliciting your consideration and help only one during which to become involved — an act seemingly small that, on the cumulative scale of humanity, strikes the world.

The best problem going through us all, nonetheless, is methods to be with one another’s struggling. In consonance with the nice Zen trainer Thich Nhat Hanh’s perception that “when you love someone, the best thing you can offer that person is your presence,” Wiesel considers the wellspring of common love and brotherhood:

I imagine in dialogue. I imagine if individuals discuss, and so they discuss sincerely, with the identical respect that one owes to a detailed pal or to God, one thing will come out of that, one thing good. I’d name it presence. I would love my college students to be presence each time individuals want a human presence. I urge little or no upon my college students, however that’s one factor I do. To individuals I really like, I want I may say, “I’ll endure in your house.” However I can not. No person can. No person ought to. I may be current, although. And if you endure, you want a presence.

[…]

If there’s a governing principle in my life, it’s that: If any individual wants me, I have to be there.

Couple this fragment of the wholly vitalizing Conversations with Elie Wiesel with Wiesel’s stirring Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, then revisit Nick Cave on the antidote to our existential helplessness and the pioneering X-ray crystallographer and peace activist Kathleen Lonsdale on moral courage and our personal power.