All through an unusually sunny Fall in 1970, a whole lot of scholars and college at Syracuse College sat one by one earlier than a printing laptop terminal (much like an electrical typewriter) linked to an IBM 360 mainframe situated throughout campus in New York state. Virtually none of them had ever used a pc earlier than, not to mention a computer-based info retrieval system. Their arms trembled as they touched the keyboard; a number of later reported that that they had been afraid of breaking your complete system as they typed.

The contributors had been performing their first on-line searches, getting into rigorously chosen phrases to search out related psychology abstracts in a brand-new database. They typed one key time period or instruction per line, like ‘Motivation’ in line 1, ‘Esteem’ in line 2, and ‘L1 and L2’ in line 3 to be able to seek for papers that included each phrases. After working the question, the terminal produced a printout indicating what number of paperwork matched every search; customers might then slender down or develop that search earlier than producing a listing of article citations. Many customers burst into laughter upon seeing the response from a pc so distant.

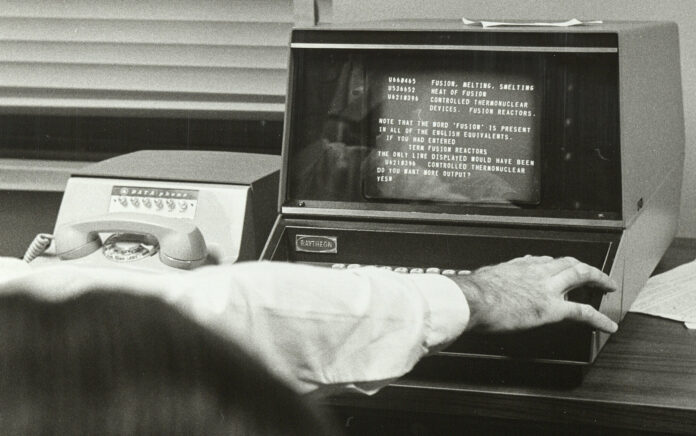

The IBM 360 mainframe computing system with printing terminal. Courtesy IBM

As a part of a phone survey afterwards, contributors had been requested to offer two or three phrases describing the expertise. Of the 78 complete phrases supplied, 21 had been the identical adjective: ‘irritating’. Individuals had hassle signing on to the system and skilled unpredictable failures, ‘irrelevant output’ and, most of all, not realizing ‘what phrases to make use of in a search’. But in addition they discovered the system intriguing and thrilling (‘enjoyable’, ‘thorough’, ‘I dig computer systems’), and 94 per cent mentioned they might use SUPARS (the Syracuse College Psychological Abstracts Retrieval Service) once more if it had been accessible. A number of supplied to maintain the experiment working previous its deadline by asking their departments to contribute funding to the mission.

This group of educational guinea pigs, largely graduate college students in schooling, psychology and librarianship, had been a part of a radical on-line search experiment run by the Syracuse College College of Library Science. SUPARS was considered one of many formidable information-retrieval research that came about between the late Nineteen Sixties and mid-Nineteen Seventies on US college campuses. A variety of components led to the surge on this analysis. Developments in computer-processing functionality for pace and storage had allowed tutorial databases and catalogues to be digitised and moved on-line. Pc terminals had been newly modular and might be positioned round campuses for decentralised entry to mainframes. And navy and trade funding for computer-based analysis was extra plentiful than it had ever been. Given the chance, tutorial librarians took benefit of the possibility to discover this costly new expertise. In flip, universities supplied unclassified environments for collaborations with company expertise corporations and navy teams; SUPARS was sponsored by the Rome Air Improvement Heart, the laboratory arm of the US Air Drive.

It’s straightforward to see why librarians of the Nineteen Seventies got down to revolutionise search. Work throughout the academy was increasing to such a level that, quickly, there wouldn’t be sufficient human librarians to assist all of it. But, to get the data they wanted, researchers would face a time-consuming, bodily concerned course of that required librarian intervention. Whereas tutorial researchers might browse new problems with journals of their subject, for a targeted search of all that had come earlier than they nonetheless needed to seek the advice of with a reference librarian to lookup the right Library of Congress topic headings inside a multivolume guide. Armed with a set of topic headings, the researcher would then search throughout the library catalogue for books and in quotation indexes for journal articles, together with subscription databases such because the Science Quotation Index in addition to hand-built bibliographies created by their college’s topic librarians. Lastly, they might bodily observe down the right books and sure periodicals that included articles they thought may be related – if the volumes occurred to be on the library cabinets.

It’s no marvel that SUPARS contributors discovered the system compelling, regardless of its limitations. And given how acquainted college librarians had been with the challenges of search, it is smart that the system they designed bypassed topic headings and quotation indexes. What’s extra stunning is that, of all the web search experiments that came about throughout this era – together with commercially targeted search methods like Lockheed’s Dialog, which has since grow to be an enterprise product – SUPARS mimicked up to date net search extra carefully than another, prefiguring a number of main options of web-search protocols we depend on greater than 50 years later.

SUPARS and different largely forgotten methods had been the forerunners of the up to date serps we now have right this moment. Whereas the favored historical past of the web valorises Silicon Valley coders – or, generally, the previous US vice chairman Al Gore – most of the unique ideas for search emerged from library scientists targeted on the accessibility of paperwork in time and house. Working with analysis and growth funding from the navy and trade, their advances could be seen in every single place within the present on-line info panorama – from basic approaches to ingesting and indexing full-text paperwork, to free-text looking and a classy algorithm utilising earlier saved searches of others, a foundational constructing block for up to date question enlargement and autocomplete. Certainly, these and plenty of different approaches developed by campus pioneers are nonetheless utilized by the multibillion-dollar companies of net search and industrial library databases from Google to WorldCat right this moment.

.jpg)

Pauline Atherton Cochrane (centre) with colleagues working within the Syracuse College Libraries on SUPARS. Picture courtesy Syracuse Libraries Particular Collections

SUPARS was designed by a librarian named Pauline Atherton (who goes by the identify of Pauline Atherton Cochrane right this moment). In 1960, aged 30 and early in her library profession, she had been the cross-reference editor of that 12 months’s revision of the World E book Encyclopedia, making certain thorough and correct cross-linking between completely different articles. By 1966, she was working on the Syracuse College libraries and within the library college, the place in 1968 she demonstrated the primary use of an internet decimal classification file to assist in search (AUDACIOUS). That very same 12 months, she established the primary computer-based instructing lab that built-in on-line search into common classroom instructing on the library college (LEEP). (Within the context of the world earlier than the web, ‘on-line’ meant establishing a networked, real-time connection between a mainframe laptop and another distant gadget, comparable to a terminal.)

The next 12 months, in 1969, Atherton designed SUPARS together with her co-investigator, Jeffrey Katzer, one other library science professor at Syracuse. The principle purpose of the SUPARS mission was to offer on-line looking at an enormous scale to be able to study as a lot as attainable about how customers searched on-line, how they felt about it, and what they wanted to go looking higher. To take action, the workforce arrange a searchable corpus of scholarly content material made accessible to your complete campus; greater than 35,000 latest entries from the American Psychological Affiliation’s Psychological Abstracts. Used for indexing and retrieval within the SUPARS system, this comprised the primary database of serious measurement accessible on-line in an unclassified setting. Whereas clearly nowhere close to the dimensions and scope of right this moment’s net search, each the consumer group and the searchable content material had been huge for the time.

Two choices from Atherton and her workforce made SUPARS actually novel. First, they stripped away all topic headings from the entries in Psychological Abstracts and made all of the phrases instantly searchable, apart from connectors comparable to ‘and’ and articles like ‘a’ or ‘the’. This made SUPARS the primary system the place intensive free textual content was accessible on-line for each looking and output. (They titled their ultimate report ‘Free Textual content Retrieval Analysis’.) Second, they saved each SUPARS search in a parallel database that might be queried alongside the abstracts themselves, making SUPARS the primary experiment that allowed customers to entry and use earlier searches to search out various phrases or approaches.

SUPARS prefigured net search by giving customers the power to go looking free textual content instantly within the paperwork themselves

Every of those options would have been novel on their very own however, to contextualise how forward of its time the mix was, it’s value taking a look at how web-search providers function right this moment. Google, Bing and different serps index net pages utilizing two main elements: crawlers seek for new pages, and frequently recrawl already discovered pages; parsers analyse the content material of pages, storing the ensuing info, together with all free textual content, in an inner database. When a consumer enters a search question, Google tries to match the phrases and phrases within the question to pages in its database and serve essentially the most related outcomes to the consumer.

Along with the phrases that searchers enter themselves, up to date web-search algorithms additionally take note of different phrases carefully associated to these within the search question, together with synonyms (comparable to a seek for ‘bike’ returning outcomes for ‘bicycle’ and ‘cycle’) and different instantly associated phrases.

Most serps may also embody phrases that had been a part of related queries carried out by others, which grow to be a part of the inner thesauri used so as to add search phrases to a consumer’s question. This means of together with associated phrases, often known as question enlargement, considerably improves the relevance of information returned. Equally, Google and different serps additionally counsel extra search phrases to customers by way of autocomplete, creating predictions primarily based on earlier searches to assist customers shortly full their queries.

SUPARS thus prefigured net search by giving customers the power to go looking free textual content instantly within the paperwork themselves, and by permitting searchers to piggyback on search methods utilized by others who got here earlier than. In the meantime, SUPARS decided the utility of all these particular person searches by way of evaluation of its transaction log. After an preliminary pilot mission, two periods of SUPARS testing had been run between October to December 1970 (SUPARS I) and November to December 1971 (SUPARS II). Atherton’s workforce concluded that free-text search was an environment friendly approach to enhance relevance (often known as ‘recall’ within the scientists’ parlance) of search outcomes – and may be simply as efficient as a search led by a analysis librarian of the human kind. What’s extra, the ever-evolving vocabulary of a system frequently adapting to human enter and behavior introduced an improve over a system primarily based on a set, ‘one-shot’ managed vocabulary of search methods up to now. The SUPARS workforce had no approach of realizing that AI-powered web-search algorithms could be doing this exact work a number of many years later, however they clearly had a way that this is able to be a brand new and efficient approach of frequently updating search outcomes.

In a 1972 letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Society for Info Science, Katzer described the reasoning behind offering a database of all earlier search queries:

The aim of this Search Knowledge Base is to assist the consumer as he tries to formulate queries to the information base of paperwork (Psychological Abstracts.) Since SUPARS is at the moment utilizing an unrestricted vocabulary, the output from the search knowledge base might assist the consumer uncover different methods to assault his matter within the doc knowledge base: It would present key phrases utilized by different matter specialists, together with a illustration of their thought processes … [W]e suppose that this can be a starting in an space which has not been sufficiently explored: the usage of consumer intelligence to enhance the entire effort which has gone into machine intelligence.

It is tempting to depict Atherton’s workforce as utopian futurists, however the SUPARS experiment was not designed with a guiding imaginative and prescient just like the open net in thoughts. It was particularly created for a future by which fewer librarians could be accessible to assist researchers in particular person. Extending the collective intelligence of others was a sensible resolution, not an idealistic one.

Atherton’s group noticed that, as a result of the brand new laptop terminal places at Syracuse had been ‘distant from a reference librarian or another human specialists within the consumer’s curiosity space’, they would wish a further supply of assist, which might be present in ‘the human intelligence of all different customers of the system’. The combination choices of different researchers was solely an alternative to a library skilled, they wrote:

Ideally, a consumer would be capable of speak with somebody aware of his curiosity space and be supplied with a wide range of phrases and different cues. The consumer might then develop or formulate a search inquiry to the system that had the specificity or exhaustiveness wanted to maximise retrieval.

As they labored with the modular terminal on campus, the SUPARS workforce noticed the longer term that was coming and what a world primarily based on distributed, networked computing would lose: an ever-larger variety of researchers had been more and more going to be working outdoors of the library, on their very own, in want of assist that librarians wouldn’t be capable of present. Atherton’s workforce wasn’t predicting a world the place skilled librarians wouldn’t be wanted; they had been getting ready for a world the place analysis would happen in lots of disparate places, too removed from a reference desk for them to have the ability to assist.

The individuals credited as visionaries imagined a world the place expertise would enhance human communication

The SUPARS experimenters additionally concluded that, whereas utilising the search phrases of others was a promising various to subject-based search, it had actual limitations. One of many ultimate SUPARS suggestions was to proceed creating managed vocabulary, explaining that ‘a necessity continues to exist in interactive free-text looking for some type of consumer vocabulary or synonym management’. They got here to this conclusion after seeing how incessantly SUPARS contributors stumbled into search vocabulary issues comparable to, in considered one of their examples, looking for ‘individuals’ as a substitute of ‘people’ and returning no outcomes. The contributors themselves missed the comprehensiveness of topic headings. In reality, as a part of the SUPARS survey, they had been requested in the event that they most well-liked a free-text system or one by which the vocabulary was extra managed: 42 per cent most well-liked the free-text system, 36 per cent most well-liked the managed vocabulary, and 12 per cent needed each.

On this approach, SUPARS is significant as each a design far forward of its time and as a counterexample to established techno-utopian histories of the web and the world large net. The individuals credited as visionaries on this historical past nearly all the time imagined a world the place expertise would enhance human communication, intelligence and effectiveness completely.

For instance, one of the vital celebrated figures on this historical past is Joseph Carl Robnett ‘Lick’ Licklider, whose concept of a common community instantly impressed the invention of ARPANET, typically described as ‘the primary web’. (Licklider was additionally deeply concerned with related Nineteen Sixties and ’70s campus experiments for on-line search; he each funded and suggested on a number of research at MIT libraries that ran throughout the identical interval as SUPARS.)

In 1968, the 12 months earlier than SUPARS was designed, Licklider’s paper ‘The Pc as a Communication Gadget’ declared that: ‘In a number of years, males will be capable of talk extra successfully by way of a machine than nose to nose’ and described a rewarding, blissful society mediated by human laptop interactions. Licklider predicted that ‘life will probably be happier for the on-line particular person’ and that ‘communication will probably be more practical and productive, and subsequently extra pleasing’. Licklider’s essay is often each predictive and rosy for this futuristic style in regards to the potential of data expertise.

Tradition celebrates individuals like Licklider for being visionary in a constructive vein. However, equally, Atherton and the SUPARS analysis workforce must be celebrated for having seen after which designed for what the longer term would lose. Increasing our group of established web visionaries to incorporate individuals like Atherton, we see a extra complicated portrait of how completely different sorts of researchers envisioned the world to return. The place Licklider noticed what we might achieve from having the ability to talk on-line with anybody on the planet, Atherton’s group noticed that we might lose skilled intermediaries; they designed for this value.

In 2022 and 2023, as the primary generative AI serps, together with tutorial serps comparable to Elicit and Consensus, had been launched to a large set of customers to each nice pleasure and scepticism, it’s equally helpful to analyse what will probably be misplaced when researchers come to depend on these instruments. Once we can merely enter analysis inquiries to create instantaneous literature evaluations, for instance, there won’t be merely an awesome constructive leap ahead. This new expertise will create an absence of grounding and context, whilst unimaginable new discoveries are made – a unique loss than what Atherton noticed, however equally each intangible and deeply consequential. With the ability to predict these penalties upfront, not mourning them as Luddites however actively contemplating the right way to assist researchers overcome them, is a lesson we will study from the SUPARS workforce.