What follows is an essay by Thomas E. Wartenberg (Mount Holyoke School), based mostly on his latest ebook Thoughtful Images (OUP, 2023).

The primary illustration of philosophy that I’ve been in a position to establish is the Roman mosaic from Pompeii made within the first century C.E. that you simply see right here. It exhibits a gaggle of males centered on a standing man who’s talking. The figures have been recognized as Plato holding a stick and pointing, surrounded by different philosophers from Historical Greece, although there may be debate about who they’re.

This lovely mosaic illustrates a facet of the Platonic follow of philosophy: it depicts a gaggle of males having a dialogue. This is a crucial side of how philosophy was completed in Historical Greece, and it accords with the well-known portrait of Socrates doing philosophy with his followers. It thus represents an advance within the illustration of philosophy, for the one traces of philosophy in earlier artistic endeavors had been the busts of well-known philosophers.

One query this beautiful work poses is what different aspects of philosophy can be illustrated. In spite of everything, philosophy poses very summary questions and its proposed solutions lack the concreteness typical of works of visible artwork. Given these info, it might sound paradoxical to say that philosophy itself moderately than its practitioners and modes of follow will be offered in a piece of visible artwork.

An account of how philosophical texts, ideas, and theories will be illustrated in visible artwork begins with the conclusion that philosophical texts are usually not as summary as may be thought. The texts that represent the Western historical past of philosophy are replete with literary photographs of varied varieties, so let’s flip to those first to grasp how philosophy will be illustrated.

Illustrating Thought Experiments

One widespread function of philosophical texts that nearly requires visible illustration is the thought experiment. A thought experiment presents an imaginary state of affairs that readers of the textual content are purported to think about. Thought experiments include directions that assist readers perceive their level. The state of affairs and the directions are equally vital elements of a philosophical thought experiment.

We will discover examples in Plato’s dialogue the Republic, a textual content studded with thought experiments. Early within the first ebook, to indicate the inadequacy of a proposed definition of justice as giving folks what they’re owed, Socrates asks his interlocuters to think about a weapon that they’ve borrowed from a person. Suppose, Socrates continues, that the person has suffered a breakdown and now would pose a danger had been the weapon returned to him. Wouldn’t it nonetheless be simply to take action because the proposed definition suggests?

As a result of Socrates’ interlocuters—in addition to readers of the dialogue—have the instinct that they need to not return the weapon to the one that has suffered a breakdown, it turns into obvious that the proposed definition is insufficient. Socrates has offered a counterexample to the proposed definition within the type of a thought experiment.

The Republic has numerous extra elaborate thought experiments. One in all them, the Parable of the Cave, is particularly vital to our dialogue as a result of artists have illustrated it persistently down by the ages. Plato presents this parable to be able to, amongst different issues, clarify the character of his metaphysics in keeping with which the objects we usually take to be actual—corresponding to tables and chairs, bushes and grass—are merely “appearances” of a extra elementary actuality, the Varieties. One motive why Plato holds that abnormal issues can’t be the final word actuality is that they’re always altering. Tables and chairs break and collapse; bushes and grass wither and die. As a result of they’re topic to decay, such issues can’t be totally actual.

In distinction, Plato holds that the Varieties by no means change and are what they’re eternally. A person who’s good-looking will lose that trait as he ages, however handsomeness itself—the usual by which we decide the person to be good-looking within the first place—doesn’t change. It merely applies to various things at totally different occasions.

Right here is the state of affairs offered within the Parable of the Cave: There’s an underground cave lit solely by a hearth. In entrance of the fireplace is a gaggle of people who find themselves certain from head to toe in order that they will solely see the wall of the collapse entrance of them. On the wall of the cave a sequence of shadows are solid by the fireplace as objects are paraded in entrance of it. The prisoners can solely see these shadows, which they take to be actual issues.

Though there may be extra to the Parable than this, what I’ve simply summarized is adequate for my functions, for it’s this scene that a number of the illustrations of the Cave depict. That is the case with the primary illustration of it that I do know of it, a portray attributed to Michiel Coxcie (1499-1592), La Grotte de Platon (16th century).

How precisely does this portray illustrate the Parable of the Cave? Two ideas I introduce in Considerate Photos will assist reply this query. They’re constancy and felicity and each are central options of illustrations of texts. To exhibit constancy, a picture should be trustworthy to the textual content it goals as an instance, that’s, embrace visible options comparable to the linguistic description. We will see many options of Coxcie’s portray embody constancy. The folks within the image are chained, indicating that, as Plato specifies, they’re prisoners. On the wall behind the prisoners, a central flame shines mild throughout a couple of objects (atop the pillars) and casts shadows of these objects (and the pillars) down the concave wall behind the prisoners. All of those options exhibit constancy to Plato’s textual content.

Some options of the portray, nonetheless, sacrifice constancy for felicity. An illustration that’s felicitous contributes to the integrity of the work in its new medium. So, though the position of the prisoners principally reclining on couches in a circle in states of semi-nudity departs from Plato’s description, it satisfies norms for work that had been prevalent within the sixteenth century when the portray was created and helps make the portray a murals in its personal proper.

An fascinating function of the portray is the presence of the 2 totally clothed figures on the high of the circle of prisoners. They stand out from the partially nude prisoners however their position will not be clear. The one on the best seems to have two chains throughout his chest, marking him as a prisoner, although it’s unclear why he’s totally clothed and his calm demeanor distinguishes him from the others. The totally clothed determine on the left appears to be trying rigorously on the photographs on the cave’s wall and thus represents the concept that the prisoners are deluded in regards to the nature of actuality by their commentary of shadows moderately than actual issues. Though the colour of the robes of those two figures provides to the visible affect of the portray, the rationale for his or her look stays unclear.

La Grotte de Platon demonstrates the significance of constancy and felicity in illustrations. These conflicting norms outcome within the creation of artworks which can be each trustworthy to and totally different from the textual content they illustrate, with their departures making for a piece that has extra integrity in its new creative medium.

Illustrating Wittgenstein

Thought experiments are usually not the one elements of philosophical texts which have been illustrated by artists. A number of well-known conceptual artists have, for instance, illustrated passages from the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein’s texts are sometimes obscure and troublesome to interpret. For that reason, illustrations of them are welcome. Illustrations make clear the works they illustrate, serving to viewers perceive the customarily troublesome and summary concepts of philosophy.

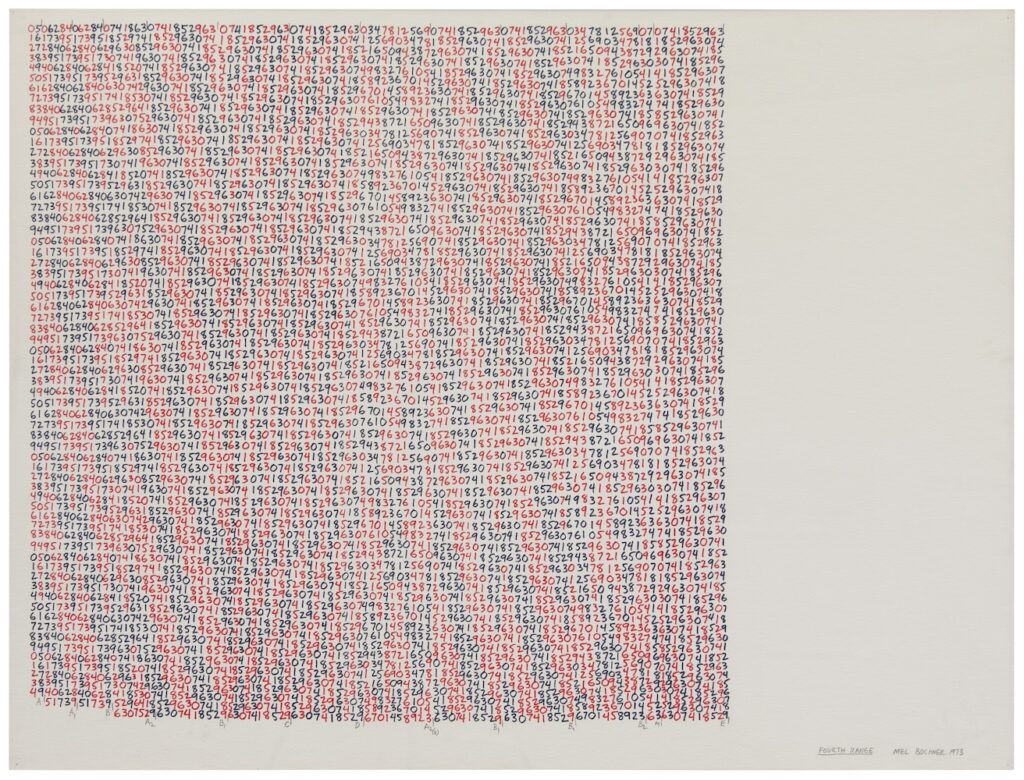

Here’s a drawing by the modern artist Mel Bochner (1940– ), who is commonly characterised as a conceptual artist. Fourth Vary (1973) illustrates a declare made by Wittgenstein in his posthumously revealed ebook, On Certainty (1969).

In On Certainty, Wittgenstein targets the philosophical principle of skepticism, the view that human beings don’t possess data, beliefs whose reality is for certain or indubitable. This principle will be traced again at the least to René Descartes who maintained in his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641) that it was potential to doubt the reality of each one in all his beliefs, and in so doing discovering that nothing is for certain. (He goes on to establish one perception that’s proof against doubt in his well-known Cogito ergo sum, however we are able to ignore that for our functions.) This thesis of Descartes’ is the results of what’s termed “hyperbolic doubt,” a doubt that extends to all of 1’s beliefs.

Wittgenstein, quite the opposite, maintains that hyperbolic doubt will not be genuinely potential. He maintains that doubt all the time happens in a selected context. Extra particularly, he argues that doubts—or errors which lie at their foundation—can solely come up when a rule has been violated. We will doubt the veracity of the assertion “2+2=5” as a result of we all know that 2+2=4 in keeping with the foundations of arithmetic. We acknowledge that asserting “2+2=5” is a mistake as a result of it violates these guidelines.

Regardless of this intuitive instance, Wittgenstein’s argument is troublesome to comply with and perceive. We nonetheless may be not sure why a rule is important to establish a mistake. Though Wittgenstein makes an attempt to make clear the rationale for this, readers could also be unsure about his reasoning. And that’s the place Bochner’s illustration turns into useful. However for it to help readers in understanding Wittgenstein’s argument, they’ve to look at the drawing very rigorously. (I’ll give a fast interpretation of it right here. For a extra prolonged evaluation, see Considerate Photos, chapter 8.)

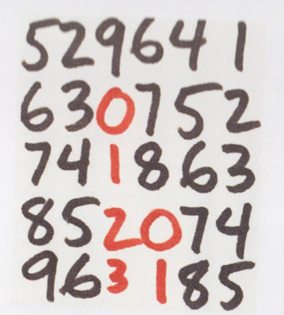

Viewers can see the patterns of ‘V’s and ‘W’s when trying on the work as an entire, however in addition they have to deal with its particulars if they’re to grasp the way it illustrates Wittgenstein’s declare. Discover the next options of the work: It’s composed of repeated sequences of the numerals ‘0’ by ‘9’ in numerical order. These numeric sequences, written vertically, alternate between crimson and black. On the finish of every column, the sequence continues within the subsequent column to the best and not using a break within the numerals, though it may possibly begin on the high or the underside, relying, and the colour of the sequence can change at this level although it needn’t. Every ten columns type what I name a “block.” In a block, the next guidelines stay fixed: people who specify the size of a column, these specifying whether or not the sequence will proceed on the backside or high of the subsequent column, and at last these specifying whether or not the colour of that sequence will stay the identical or change. Nonetheless, these guidelines will range from one block to the subsequent, a truth indicated by letters on the backside of the block—A, A1, B, and so on.—that point out the presence of a selected algorithm.

In following the sequences of numerals, the particularly attentive viewer will discover {that a} mistake happens within the fifth column of the fourth block when a black sequence ends with an ‘8’ moderately than a ‘9.’ Viewers acknowledge this as a mistake as a result of they notice it violates the foundations by the use of which the drawing has been created. Solely as a result of viewers have seen the presence of the foundations are they in a position to establish the transfer from a black ‘8’ to a crimson ‘0’ as a mistake.

Bochner’s drawing thus illustrates Wittgenstein’s rivalry that it’s the presence of a rule that’s required to acknowledge {that a} mistake has been made. And this helps make viewers grasp the rationale for Wittgenstein’s declare. Bochner succeeds as a result of he has invented a “numbers sport,” an analogue to Wittgenstein’s notion of a language sport, whose guidelines I’ve simply defined. This “illustration” of Wittgenstein’s claims about language and data is an modern option to display the reality of the thinker’s view.

Plato and Wittgenstein are among the many philosophers whose works have been illustrated most frequently by artists. As now we have seen, Plato’s theories had been illustrated by artists starting within the sixteenth century. However the curiosity didn’t finish there. Artists have discovered Plato’s philosophy an acceptable topic for illustration all through the ages, even into the twentieth and twenty first centuries. The well-known conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth produced each an set up, One and Three Chairs (1965), that illustrates and critiques Plato’s philosophy and a neon work that illustrates one other one of many thought experiments within the Republic, viz the Divided line, by actually replicating a portion of Plato’s textual content in vivid white neon tubing. The latter was included in a 2018 exhibition on the Getty Museum in Los Angeles entitled Plato in L.A. that featured works by 11 artists impressed by Plato.

The rationale for artists’ curiosity in Plato is clear. As a result of so a lot of his philosophical texts have come all the way down to us of their full type, Plato exerted an incredible affect on Western thought, an affect that prolonged to artwork. The vividness of the literary photographs in his work, together with not solely the Allegory of the Cave but additionally the Divided Line, virtually cry out for visible renditions. (His scholar Aristotle was additionally very influential, and plenty of artists have illustrated his writings, as I focus on in chapter 3 of Considerate Photos.)

Wittgenstein has additionally fascinated artists. Conceptual artists had been notably focused on his work and depicted his concepts in modern methods. As he did with Plato, Kosuth created items corresponding to 276. (On Color Blue) that illustrated Wittgenstein’s concepts by rendering his phrases in neon. Bruce Nauman additionally included Wittgenstein’s phrases in A Rose Has No Teeth which reproduces in a lead plaque a comment of Wittgenstein’s from the Philosophical Investigations (¶314). Jasper Johns included a drawing of the duck-rabbit, a well-known drawing Wittgenstein included within the Investigations, in Seasons: Spring (1987), a piece that features different allusions to Wittgenstein’s dialogue of aspect seeing within the Investigations. Each Eduard Paolozzi and Bochner made a sequence of prints that illustrated different claims made by Wittgenstein, and Maria Bussmann’s drawings included illustrations of Wittgenstein’s early ebook, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921). (For extra on this, see Considerate Photos, chapters 7 and eight.)

Why did Wittgenstein exert such a strong affect on artists within the second half of the 20 th century? One issue was the significance attributed to language by each artists and philosophers within the twentieth century. Wittgenstein’s views had been one of many central causes for this shift in philosophical curiosity away from the character of the thoughts and its concepts and onto language because the car for expressing these concepts. Conceptual artists shared an curiosity in language and due to this fact naturally gravitated to Wittgenstein due to this shared concern.

Wittgenstein’s aphoristic writing fashion additionally enabled artists to make use of language-based illustrations of his works. It might be onerous to extract an acceptable citation from, say, the writings of Kant to show in a murals, with the potential exception of his well-known assertion that two issues impressed him with awe, the starry heavens above and the ethical regulation inside. However with Wittgenstein, because the examples of Kosuth, Nauman, and Bochner attest, it was simple to seek out quotations worthy of show in an paintings.

After which there was the determine of Wittgenstein himself. His revolutionary concepts and seriousness of objective impressed a coterie of followers who took him to be a latter-day Socrates, the one different secular determine within the historical past of European philosophy to exert such a personalised affect. Like Socrates, Wittgenstein attracted disciples not only for his philosophical views but additionally for the single-mindedness with which he pursued his philosophical investigations. Norman Malcolm’s Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir presents a vivid image of this inspirational thinker. Paolozzi’s As Is When: A series of screenprints inspired by the life and writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1964-65) attests to the attraction that Wittgenstein’s life exerted on artists.

The examples of Plato and Wittgenstein present how vital philosophical theories are for a lot of artists. There are lots of the reason why artists select as an instance philosophical texts, concepts, and theories. Amongst them may be a want by artists to indicate that artwork will be the equal of written texts as a car for the transmission of philosophical concepts regardless of the latter usually being taken to be the first supply for philosophical concepts. The artists who’ve illustrated philosophical concepts haven’t completed so slavishly, as if artwork might solely be the handmaiden of philosophy. Moderately, artistic endeavors that illustrate philosophy are ingenious of their presentation of summary philosophical concepts in concrete visible type whilst they attest to the significance of written philosophy as a supply of creative inspiration.

Thomas E. Wartenberg is the creator of Pondering on Display screen: Movie as Philosophy (Routledge) and Large Concepts for Little Youngsters: Educating Philosophy By way of Youngsters’s Literature, amongst different works. He’s Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Mount Holyoke School.