In ten billion years, the Solar will run out of hydrogen and burn out, swallowing the interior planets of our Photo voltaic System into the abyss of its collapse because the outer planets drift farther and farther. In time, the cosmos itself will run out of power and none will probably be left to succor life — the very fact of it or the opportunity of it — because the universe goes one increasing into the austere vacancy of pure spacetime. So will finish the quick line of life within the ledger of eternity. Within the meantime, we’re right here on our unbelievable planet, residing our unbelievable lives — perishable triumphs in opposition to the immense cosmic odds of nonexistence, haunted by our earthly existential loneliness nested into our cosmic loneliness. Is it any marvel that, since we first regarded up on the night time sky, we have now been craving to seek out what Whitman known as “beings who stroll different spheres,” trying to find life on different worlds that tells us one thing about easy methods to stay on this one, one thing in regards to the deepest that means of life itself?

Planetary scientist Sarah Stewart Johnson takes up these questions in The Sirens of Mars: Searching for Life on Another World (public library) — a sweeping civilizational memoir of our eager for cosmic companionship and the actual pull of the purple planet on our creativeness, rendered by our science into an affirmation of Ray Bradbury’s Mars-fomented insistence that it’s a part of our nature “to start out with romance and construct to a actuality,” residing proof of Richard Feynman’s passionate conviction that “nature has the greatest imagination of all.”

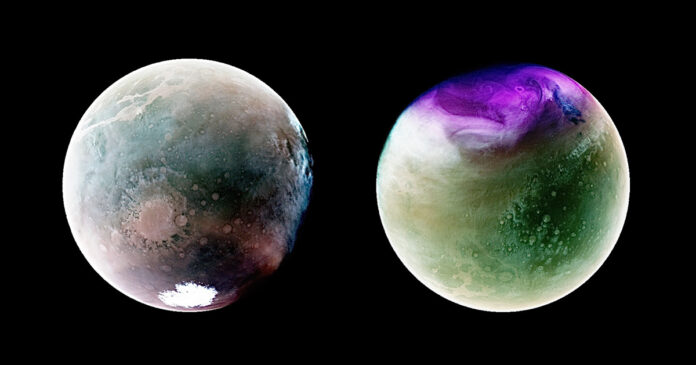

Reverencing the lengthy arc of transmuting principle into fact, Johnson traces how we went from the illusory Martian “canals” of the early observers to the invention of actual water-lain sedimentary rocks by our area probes, how all of the issues we received improper paved the way in which for the revelation of actuality — a reminder, she observes, that “the reality is usually a chimeric factor, the collapse of an abiding perception is all the time only one flight, one discovering, one picture, away.”

Throughout the centuries, this romance of actuality is populated by some exceptional characters: We meet the naturalist and newbie astronomer who, satisfied that Mars was an undiscovered wilderness and its canals had been fabricated from vegetation, strode into city in the midst of a World Battle on one in every of his two horses, Jupiter and Saturn, to cable his reviews; the commodities dealer turned adventurer who, after swimming the English Channel and climbing many of the world’s tallest mountains, grew bored of Earth and got down to observe Mars from a balloon, solely to be swarmed in a savage thunderstorm, barely surviving his crash into the shark-infested Coral Sea; the girl who realized to grind telescope mirrors when she was ten, grew to become the primary in her household to go to school and the primary in her highschool to earn a doctorate, then remodeled planetary cartography by devising an elaborate laser-based system for mapping the topography of Mars whereas rearing two young children.

Johnson’s personal seek for life on different worlds started by finding out life in probably the most otherworldly areas of this one. Plumbing the Siberian permafrost for proof of historic micro organism, she finds herself holding cells twenty thousand occasions her personal age. An epoch after Little Prince creator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry contemplated the desert and the meaning of life whereas stranded within the Sahara, she pitches a small yellow tent within the eerie expanse between Loss of life Valley and the Mojave Desert, studying Blake and Dostoyevsky and West with the Night like sacred texts, probing them for clues in regards to the that means of all of it, in regards to the nature and thriller of life. She displays:

All I wished was to seek out some stable factors, some technique to triangulate, some approach to sample a way of human understanding onto the huge bodily world round me, a world marked by human absence. Quickly, although, I started to understand the Granite Mountains weren’t as intensely empty as they appeared. After I’d first gazed into the Mojave, all the pieces appeared muted. All the colour had been drained, sipped away by the parched air. The crops had been a whitish khaki inexperienced, like fistfuls of dried herbs. I had the urge to spit on them, considering it was the least I may do, a small act of kindness. However after some time, my senses began to regulate. The sagebrush started to seem like splashes, nearly like raindrops hitting a lake. I began to see the life throughout me — within the spine-waisted ants and blister beetles, even in the dead of night varnish of the desert rocks, a sheen doubtlessly linked to microscopic ecosystems… I had a visceral sense of the world popping from two dimensions into three, of seeing a panorama in a method I’d by no means seen it earlier than.

It’s this craving to grasp the fundaments of life that drives Johnson towards the thriller of Mars. Nonetheless in her twenties, she turns into a part of the historic Alternative mission and watches in awe because the rover beams again the primary photographs of the immense Endurance Crater’s partitions — an unprecedented glimpse of “layers that had been stacked just like the pages of a closed ebook, one second in time pressed shut in opposition to the subsequent,” hinting on the planet’s historical past and on the attainable way forward for our personal world. She recollects:

Ours had been the primary human eyes to see into that mysterious abyss, and it was one of the breathtaking issues I’d ever seen. As I stared into the middle of the crater, I felt like Alice in Wonderland falling by means of a rabbit gap. “What is that this world?” I assumed, there on the verge of Endurance, my eyes large. “What is that this piercingly wild place?” The large cavity was laced with hummocks of sand. Essentially the most ethereal gossamer dunes crammed the void at its heart, not like any dunes I’d ever seen. They regarded like egg whites whipped into tender pinnacles. And enveloping the perimeters, there was undulating outcrop, lower with attractive striations, deeper than I used to be tall.

In between peering into fractures, finding out chemical gradients, and on the lookout for proof of subterranean aquifers, the search is laced with existential questions — questions Voltaire took up epochs in the past in his visionary parable Micromégas, from which Johnson attracts inspiration; query Carl Sagan and Ray Bradbury contemplated in their own reckoning with Mars. Essentially the most disquieting of them is the query of what life appears like within the first place — maybe Martian life is of substance so alien and scale so discrepant that we would not even acknowledge it; maybe it’s composed of a wholly new biochemistry, constructed upon a wholly totally different molecular basis, which we have now neither the instruments nor the minds to discern.

In a passage that echoes the sentiment on the coronary heart of “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” — Whitman’s timeless gauntlet on the limits of scientific information — Johnson considers our creaturely blind spots:

We have now human brains inside human skulls, and we perceive little of what surrounds us. The boundaries of our notion and information are palpable, particularly on the extremes, like after we’re exploring area. There may be so little knowledge to inform us who we’re and the place we’re going, why we’re right here, and why there’s something somewhat than nothing. That is the affliction of being human in a time of science: We spend our lives struggling to grasp, when typically we can have performed properly, peering out by means of these slender chinks, simply to apprehend.

Nonetheless, we go on looking out, go on attempting to grasp, as a result of the search itself shines a sidewise gleam on the last word questions pulsating beneath our touchingly human lives. Johnson writes:

We’re distinctive and bounded, and we could be in decline, for we all know that species come and go. We’re a finite tribe in a brief world, marching towards our finish.

And what of life itself? Should or not it’s finite as properly? What if life is a consequence of energetic methods? What if the nothing-to-something has occurred repeatedly and, as a result of the chinks in our cavern are so small, we don’t comprehend it? For me, that is what the seek for life quantities to. It’s not simply the seek for the opposite, or for companionship. Neither is it simply the seek for information. It’s the seek for infinity, the seek for proof that our capacious universe may maintain life elsewhere, in a unique place or at a unique time or in a unique kind.

However maybe loveliest of all is that tucked into her passionate seek for life on one other world is her passionate love letter to this one — a soulful reminder that whereas we’re expending superhuman assets on trying to find a mere microbe on Mars, we live on a planet able to bushes and bioluminescence and Bach. It’s on this world that she learns simply how uncommon life is, and the way attainable. “Wherever life can develop, it would. It’ll sprout out, and do the very best it could actually,” Gwendolyn Brooks wrote in one of her finest poems — a mirthful truth Johnson discovers whereas ascending the desolate summit of Hawaii’s Mauna Kea volcano:

Because the highway climbed, we handed the tree line, then the final of the scrub and the final of the lichens, till we had been above even the clouds. The panorama was grey and purple and black in each path; in locations it even smoldered with a sheen of purple. There have been shards and ash and cinder cones. It felt like a bruise, crystallized on the earth. Someday, when everybody was having lunch, I wandered over to take a look at the view from a distant ridge, the place the stable lava gave approach to pyroclasts and tephra. With out actually noticing, I used to be kicking on the rocks as I stepped. I overturned a surprisingly giant one with the toe of my boot, and as my eyes fell to my toes, I startled. Beneath the vaulted facet of that adamantine black rock, a tiny fern grew, its defiant inexperienced tendrils trembling within the air. There within the midst of all that shattered silence was a tiny splash of life. I crouched right down to see it higher.

[…]

It was simply so impossibly triumphant. I couldn’t pull myself away; I checked out it for therefore lengthy that the others needed to come discover me. I confirmed it to them, however I didn’t have the phrases to elucidate its magnificence, its significance. I couldn’t inform them that by some means, huddled underneath a rock, rising in opposition to the chances, that fern stood for all of us.

The Sirens of Mars is a wondrous learn in its entirety. Complement it with Annie Dillard — whom Johnson learn in that desert tent — on our planetary destiny, then revisit this breathtaking animated poem from former U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy Okay. Smith’s assortment Life on Mars.