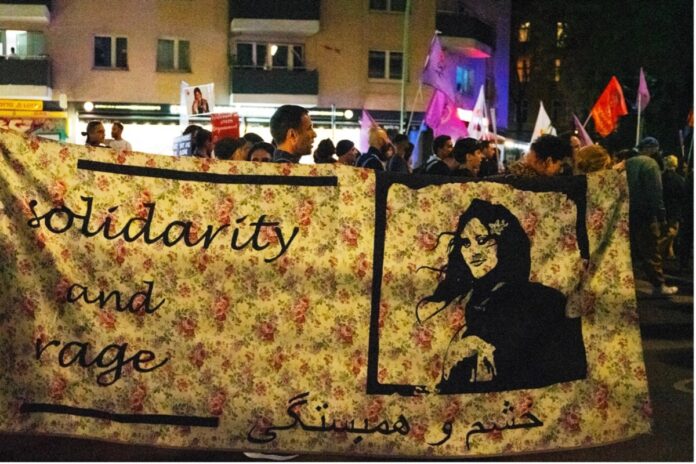

One yr has handed because the tragic demise of Mahsa Jina Amina by the hands of Iran’s morality police. Her demise turned the start of the Girl Life Freedom motion in Iran. Jina Amini (as a result of she was a member of the Kurdish minority, I’ll use her unique identify, Jina, as an alternative of the colonial identify, Mahsa) was arrested as a result of what the police noticed as improper hijab, an accusation leveled towards 1000’s of Iranian ladies because the Islamic Revolution in 1979 and the implementation of the necessary hijab legislation. In the course of the Girl Life Freedom protests, some two million folks got here to the streets, and the Twitter hashtag #mahsaamini broke the world report of 284 million tweets. These women-led protests focused primarily the necessary veiling legal guidelines in Iran, and Girl Life Freedom (‘Jin, jiyan, azadî’ in Kurdish, ‘zan, zendegi, azadi’ in Farsi) turned a slogan in protection of girls’s freedom of selection and bodily autonomy, and so introduced collectively a wide range of oppressed teams. With its attribute unveilings, head-scarf burnings, and different seemingly anti-religious symbolic gestures, the Girl Life Freedom motion confused these observers who had understood resistance to the veil as principally a Western and Islamophobic transfer. On this piece, I replicate on the implications of this motion for our present understanding of the hijab in feminist discourse.

For a very long time, what students (like Leila Ahmed and Serene Khader) name colonial feminism or missionary feminism has thought-about the hijab to be an indication of oppression, lack of autonomy, cultural and civilizational backwardness, and all in all absolutely the reverse of what feminist emancipation appears like. The catch on this reductive and hasty understanding of the hijab was that it served as a self-congratulation of white tradition for its supremacy and the liberty of white ladies at a time when non-western ladies barely loved something like feminist emancipation and nonetheless lacked fundamental rights and freedoms. The empty and instrumental use of pseudo-feminist rhetoric in colonial discourse turns into all of the extra apparent in mild of the truth that usually those who pretended to be probably the most upset in regards to the oppression of girls within the colonies had been on the identical time harsh opponents of feminist change in their very own nations. In his piece “Algeria Unveiled,” Frantz Fanon discusses the racist character of western colonial perceptions of girls’s oppression, displaying how colonial powers search to dominate cultural indicators such because the veil and rework them into symbols of the backwardness of pre-colonial cultures. These views will not be solely a factor of the previous, however proceed to be influential in our time within the type of the racialization of the hijab, xenophobic sentiments towards Muslim immigrants, and discrimination towards hijab-wearing ladies in numerous contexts. Neocolonial feminism has adopted and preserved the discourse of colonial feminism, not solely deeming different cultures inferior, but additionally supporting navy intervention within the identify of saving (Muslim) ladies, as we noticed within the case of the invasion of Afghanistan.

Though this reductionist, colonial (and racist) view in regards to the hijab nonetheless exists in feminist discourse, happily, it has been more and more challenged in the previous few many years, partly due to the work of postcolonial and decolonial feminists who’ve problematized the white colonial bias of those views. Leila Abu-Lughod addressed this downside within the context of post-9/11 politics, arguing that “our stereotyping of Muslim ladies additionally distracts us from the thornier downside that our personal insurance policies and actions on the planet assist create the (generally harsh) situations wherein distant others dwell.” Saba Mahmood’s influential work additionally challenged the simplistic view that each one pious Muslim ladies who observe conventional non secular guidelines are oppressed, and traced this view again to Western anxieties about types of life that don’t correspond to liberal secularism. Feminist philosophers Alia Al-Saji and Falguni A. Sheth have explored the racialization of the hijab within the context of discriminatory politics within the west and have analyzed the unfair prejudices, hostile attitudes and dangerous beliefs that represent the cultural racism towards Muslim ladies. These our bodies of literature have contributed to the creation of a brand new strand within the feminist discourse the place the critique of the hijab is considered entangled with the biases and shortcomings of the white gaze and the lengthy historical past of missionary feminism.

What stays under-discussed within the feminist theoretical engagements with the hijab are the political dimensions of the hijab past the white gaze, i.e., how the hijab capabilities as a cultural norm and the way it’s skilled by Muslim ladies, particularly in Muslim-majority nations like Iran. Most of this literature is concentrated on the critique of western liberalism or the dialogue of discrimination towards Muslims within the west—maybe unsurprisingly, because the literature can be written by students working at western universities. Nonetheless, within the aftermath of political occasions just like the Girl Life Freedom motion, it turns into clear how little we all know in regards to the politics of hijab within the World South. Abu-Lughod’s argument in regards to the self-serving nature of the western obsession with the oppressed Muslim lady may need been well timed within the context of post-9/11 politics, but it surely lacks rigor from a feminist perspective because it in the end downplays gendered oppression in Muslim-majority nations like Afghanistan and Iran. Abu-Lughod is definitely proper in writing that “If we predict that U.S. ladies dwell in a world of selection concerning clothes, we have to look no additional than our personal codes of gown and the customarily constricting tyrannies of trend,” however for these of us who’re dedicated to an understanding of feminism that’s transnational, the critique of gendered oppression and lack of selection in western societies and non-western societies will not be mutually unique. Arguing that Muslim ladies will not be oppressed and don’t want emancipation is just a harmful over-correction of missionary feminism.

Within the context of Iran, the Islamic Revolution was the start of a brand new period of policing ladies’s our bodies. The establishment of public gown codes compelled all ladies to put on the hijab or face authorized punishment (policing ladies’s our bodies, nonetheless, didn’t begin with the revolution however was additionally a attribute a part of the politics of the Pahlavi period, particularly exhibited within the so-called necessary de-veiling of 1936). It’s secure to say that 1000’s of girls had been verbally and bodily attacked for his or her supposedly improper hijab (many movies of which you’ll find on-line) earlier than the tragic demise of Jina Amini triggered a sequence of nationwide protests towards necessary hijab. Some observers argue that these protests will not be a lot in regards to the veil, however extra about freedom and autonomy. I feel they’re about each. We must always not draw back from acknowledging that necessary hijab has develop into an oppressive pressure towards ladies’s autonomy over their very own our bodies, and from understanding why that’s. Hoodfar argues that obligatory hijab was launched by the Islamic regime in Iran “partly in celebration of its victory of the modernist state of the shah, and partly as a way of realizing its imaginative and prescient of ‘Islamic’ Iran.” Moallem’s scholarship on the politics of patriarchy in fashionable Iran exhibits us how the concept of “Islamic femininity” that turned the image of originality and indigeneity is a response to the crises of (Iranian) modernity and must be understood within the context of transnational relations of energy. The thought of necessary hijab will not be rooted in Islam or Iranian tradition. Quite, it was a political formation responding to, on the one hand, the violence of secular fundamentalism and the top-bottom modernization through the Pahlavi period and, on the opposite, the period’s imperialist politics, which engendered emotions of alienation and frustration and revealed the necessity for a brand new development of indigenous custom as refuge. Ladies had been compelled to be carriers of indigenous non secular authenticity in lots of anti-colonial contexts (as Chatterjee’s work exhibits), and Iran was no exception. Necessary hijab, removed from being an issue of custom, is in a way each a product of colonial modernity and the anti-colonial resistance towards it. In necessary hijab, we see an attention-grabbing case of policing ladies’s our bodies wherein transnational relations of energy and native anti-imperialist sentiments unite towards ladies and their freedom of selection. Though veiling is seen merely as a conventional type of clothes by many, a more in-depth look exhibits that it has been, like another merchandise of clothes, a product of historic relations of energy. Protestors in Iran and the Iranian diaspora present of their indicators and slogans that these protests will not be towards an oppressive custom, or one corrupt authorities per se, however towards patriarchy’s management over ladies’s our bodies in all of the complicated varieties that it takes.

We will consider the resistance of the Girl Life Freedom motion as an invite to a feminist evaluation that bases the necessity for feminist critique of non secular cultures and types of life on the reality of the essential practices and native types of resistance, and never within the summary skepticism about faith, non-western cultures, or Islam as such (because it has usually been assumed within the discourse of missionary feminism). This critique can examine oppressive results of gendered gown codes such because the hijab by means of a multi-directional lens that analyzes the transnational colonial and racial constructions alongside the misogynistic politics of native governments and communities. Right here Foucault’s concept about native types of resistance as catalysts for recognizing and understanding relations of energy is useful. If we take the voices of native activists and advocates for social justice and their demand for freedom critically, it turns into evident that feminist freedom doesn’t lose its relevance for Muslim ladies simply because it’s instrumentalized by orientalist and imperialist discourses. Maybe the higher manner of being anti-imperialist feminists is by acknowledging that imperialism will not be all-encompassing, that its discourse will not be the one speech on the planet, and that we’ve got different voices to hearken to. As feminist students, informing ourselves about native types of resistance past the borders of the World North and fascinating with them in our work will not be at all times straightforward, however this issue stays a part of the duty of transnational feminist solidarity.

Zeinab Nobowati

Zeinab Nobowati is a PhD candidate in Philosophy on the College of Oregon. She works on social political philosophy, feminist philosophy and postcolonial principle.