Each evening, for each human being that ever was and ever can be, the Moon rises to remind us how improbably fortunate we’re, every of its craters a monument of the chances we prevailed in opposition to to exist, a reliquary of the violent collisions that cast our rocky planet lush with life and tore from its physique our solely satellite tv for pc with its miraculous proportions that render randomness too small a phrase — precisely 400 occasions smaller than the Solar and precisely 400 occasions nearer to Earth, so that every time it passes between the 2, the Moon covers the face of our star completely, thrusting us into noon evening: the rare wonder of a total solar eclipse.

It’s unimaginable to know this and never see the miraculous in its nightly gentle.

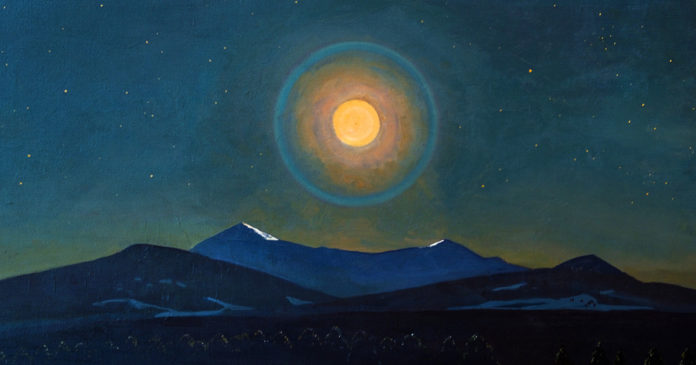

Moonlight transforms the landscapes of daytime, dusts them with the numinous.

“The sky was a wierd royal-blue with all however the brightest stars quenched, whereas on both facet the mountains had been remodeled into silver barricades, as their quartz surfaces mirrored the moonlight,” Dervla Murphy wrote in Pakistan.

“We discovered many pleasures for the attention and the mind… within the play of intense silvery moonlight over the mountainous seas of ice,” Frederick Cook dinner wrote in Antarctica.

“All of the bay is flooded with moonlight and in that pale glow the snowy mountains seem whiter than snow itself,” Rockwell Kent wrote in Alaska.

I keep in mind being small and lonely, these infinite summers within the mountains of Bulgaria, ready for dusk, ready for the Moon to solid its comfortable gentle upon the sharp edges of tomorrow and provides the bygone day one thing of the everlasting.

Moonlight transforms the landscapes of the soul: It transported Leonard Cohen to where the good songs come from; Sylvia Plath present in it a haunting lens on the darkness of the mind; for Toni Morrison, loving moonlight was a measure of freedom; for Virginia Woolf, it was a magnifying lens for love as she beckoned her lover Vita to “dine on the river together and walk in the garden in the moonlight.”

I’ve encountered no extra lovely account of this twin transformation than a passage from Watership Down (public library) — the marvelous 1973 novel that started with a narrative Richard Adams dreamt as much as entertain his two younger daughters on a protracted automobile journey. Nested halfway by way of his allegorical journey story of rabbits is Adams’s serenade to moonlight:

The complete moon, properly risen in a cloudless japanese sky, lined the excessive solitude with its gentle. We’re not aware of daylight as that which displaces darkness. Daylight, even when the solar is obvious of clouds, appears to us merely the pure situation of the earth and air… We take daylight as a right. However moonlight is one other matter. It’s inconstant. The complete moon wanes and returns once more. Clouds might obscure it to an extent to which they can’t obscure daylight.

Adams exults in moonlight as a kind of unbidden graces that give unusual life a “singular and marvelous high quality” — a grace that didn’t must exist and is on this sense pointless, like most of the lovelies issues in life, which C.S. Lewis captured in asserting that “friendship is unnecessary, like philosophy, like art, like the universe itself [and] has no survival value; rather it is one of those things which give value to survival.”

A century after Walt Whitman exulted that the Moon “commends herself to the matter-of-fact people by her usefulness, and makes her uselessness adored by poets, artists, and all lovers in all lands,” Adams writes:

Water is important to us, however a waterfall just isn’t. The place it’s to be discovered it’s one thing further, a wonderful decoration. We’d like daylight and to that extent it’s utilitarian, however moonlight we don’t want. When it comes, it serves no necessity. It transforms. It falls upon the banks and the grass, separating one lengthy blade from one other; turning a drift of brown, frosted leaves from a single heap to innumerable flashing fragments; or glimmering lengthways alongside moist twigs as if gentle itself had been ductile. Its lengthy beams pour, white and sharp, between the trunks of timber, their readability fading as they recede into the powdery, misty distance of beech woods at evening. In moonlight, two acres of coarse bent grass, undulant and ankle deep, tumbled and tough as a horse’s mane, appear as if a bay of waves, all shadowy troughs and hollows. The expansion is so thick and matted that even the wind doesn’t transfer it, however it’s the moonlight that appears to confer stillness upon it. We don’t take moonlight as a right. It’s like snow, or just like the dew on a July morning. It doesn’t reveal however adjustments what it covers.

These passages from Watership Down jogged my memory of a kindred reverie Aldous Huxley composed half a century earlier than Adams in his music-inspired meditation on the universe and our place in it, considering the Moon as a mirror not of the Solar however of the soul. In a splendid counterpart to Paul Goodman’s spiritual taxonomy of silence, Huxley presents a non secular taxonomy of moonlight:

The moon is a stone; however it’s a extremely numinous stone. Or, to be extra exact, it’s a stone about which and due to which women and men have numinous emotions. Thus, there’s a comfortable moonlight that can provide us the peace that passes understanding. There’s a moonlight that evokes a form of awe. There’s a chilly and austere moonlight that tells the soul of its loneliness and determined isolation, its insignificance or its uncleanness. There may be an amorous moonlight prompting to like — to like not just for a person however typically even for the entire universe.

Complement with the story of the first surviving photograph of the Moon, which modified our relationship to the universe, then savor this lovely picture-book about the Moon.