What’s the distance between the scent of a rose and the odour of camphor? Are floral smells perpendicular to smoky ones? Is the geometry of ‘odour house’ Euclidean, following the foundations about traces, shapes and angles that beautify numerous high-school chalkboards? To many, these will seem to be both unserious questions or, much less charitably, meaningless ones. Geometry is logic made seen, in any case; the enterprise of drawing unassailable conclusions from clearly said axioms. And odour is, let’s be trustworthy, a bit too obscure and vaporous for any of that. The folksy thought of odor because the blunted and structureless sense is no less than as previous as Plato, and I’ve to admit that, at the same time as an olfactory researcher, I generally really feel like I’m finding out the Pluto of the sensory programs – a shadowy, out-there iceball on a bizarre orbit.

Lately, nevertheless, issues have modified dramatically, and understanding what one may name ‘the geometry of odor’ is a area that now enlists process forces of neuroscientists working along with mathematically educated theorists and synthetic intelligence (AI) specialists. Whereas we’re notoriously unhealthy at intuiting how our minds organise phenomena like colors and smells, machines supply a possible route for outsourcing introspection, and doing it with rigour. They are often educated to imitate human efficiency on perceptual duties, they usually make accessible the inner representations they use to do that – the summary areas and coordinate frames through which the ineffable stuff of thought lives.

The current publication of an unprecedentedly complete and correct ‘odour map’ within the journal Science is a declaration of this new paradigm for odor. In the identical means {that a} map of the USA tells you that Buffalo is a bit nearer to Detroit than to Boston, the odour map can inform you that the odor of lily is nearer to grape than it’s to cabbage. That a lot could seem apparent, however the actual magic comes from the truth that any arbitrary chemical’s exact location on the odour map could be calculated. From having just a few info available a few chemical, we are able to compute that it smells, say, 13 per cent nearer to lily than to grape. By analogy, it could be one thing like having a formulation that takes in details about an unknown metropolis’s inhabitants measurement and soil composition, and spits out, appropriately, the precise longitude and latitude of Philadelphia.

A map like this isn’t simply an correct, laboriously assembled catalogue of relative areas and perceptual similarities. It’s one thing way more highly effective: a set of derived guidelines for calculating which odour goes the place. Realizing these guidelines, you possibly can apply them not simply to a small handful of chemical substances, however to your complete world of odorous chemical substances. You possibly can see the place probably the most densely populated areas are, and the place the ‘state traces’ are on the planet of smells. It is a prospect that dazzles the world’s perfumers and gourmands, and anybody else within the notoriously tough and fickle process of predicting how one thing will odor from its chemical properties.

However, much more than this, it additionally raises intriguing philosophical questions on what our noses even suppose chemical substances are, and what it means to measure their similarity. What’s it concerning the world that our noses are ‘mapping’, in different phrases, once they put lily near grape? Are they latching on to some single molecular property like a chemical’s weight or measurement? Are they calculating some sort of common fingerprint throughout a wide range of such properties? Or are they doing one thing totally different altogether, like finding molecules in an area of frequent metabolic reactions?

Apparently, the final of those appears to be extra the case. The perceptual yardstick our brains use to measure, organise and evaluate smells might finally have much less to do with what a chemist might uncover from working a pattern, and extra to do with our deep relational histories with the world. Our noses might grow to be geometers not of the world’s fastened and invariant properties, however of its developed and Earthly processes.

There’s something poetic in the concept, in an effort to crack the ‘historic sense’, the crude, most scientifically incorrigible sense, we’ve needed to watch for machine intelligence. That is in distinction with the opposite sensory modalities, which started to share their secrets and techniques within the seventeenth century to wizard-like seers bearing prisms and tuning forks.

The primary investigative template for ‘geometrising’ the senses was developed by Isaac Newton within the late 1600s. In his iconic experiments in optics, carried out in his Cambridge parlour, he uncovered a relationship between the color of sunshine and its refrangibility – the diploma to which it was bent by a easy prism. The mere description of this reality would have ranked among the many most essential scientific discoveries ever, however Newton went a step additional, and match his observations to a geometrical mannequin. Wrapping the seven main colors of the seen spectrum alongside the circumference of a circle (see determine beneath), he produced the primary ‘chromaticity diagram’ – a forerunner of the color wheels that we use to organise our fascinated with colors and their mixtures.

The circle, for Newton, was not just a few poetic flourish, however a dedication to a really explicit means of encoding color’s properties. It was an invite to tug out our protractors and rulers, and make calculations about how colors relate to at least one one other, and mix into mixtures. The parts of a three-part combination of totally saturated purple, yellow and inexperienced, for instance, could be represented because the three vertices of a triangle, with every vertex pinned on the color circle’s circumference on the appropriately labelled level. The centre of mass of this triangle is a single level within the circle’s inside, and specifies the hue and saturation of the resultant combination. Within the case of blending all seven main colors to an equal diploma, the centre of mass of the seven-pointed determine could be on the precise centre of the circle, which Newton designated as white.

There may be after all much more to color imaginative and prescient than what Newton described in his Opticks (1704), and even his contemporaries famous flaws and shortcomings in his mannequin. However, his achievement nonetheless encapsulates the ambition of the classical paradigm for sensory mapping. It seeks a mathematical correspondence between measurable and intrinsic properties of the pure world (like mild’s refrangibility, which we now attribute to wavelength), and phenomenological qualities of thoughts (like color, pitch and odor). There’s something like a Pythagorean, the-world-is-mathematics mysticism to the endeavour.

The fundamental logic of pitch notion was additionally cracked equally, with easy instruments like tuning forks and spherical ‘resonators’ used to supply pure tones of a single frequency, from which guidelines about consonant pitch mixture could possibly be derived. Pitch notion as an entire is fantastically complicated however, in broad strokes, our complete auditory system – from the tiny coiled-up cochlea of our interior ear, to the auditory parts of our sensory cortex – is constructed on the fundamental precept of organising low, center and excessive tones just like the keys of a piano. Putting neighbouring notes on a piano may also ‘strike’ neighbouring neurons in your mind.

Smell might by no means be parsed with a software as basic as a tuning fork, and it by no means acquired its Newton, nevertheless it was not for an absence of individuals attempting to comply with his lead as a geometer of the senses. The concept there may exist a small variety of ‘odour primaries’ that, by analogy to the prismatic colors, organised the world of smells has occurred to many, and the seek for these continued in earnest properly into the twentieth century.

An early and influential classification scheme for odours by the famed botanist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus, in 1756, included seven varieties: fragrant, aromatic, ambrosial (musky), alliaceous (garlic), hircine (goaty), repulsive, and nauseous. A up to date of Linnaeus’s, Albrecht von Haller, was a bit stingier along with his adjectives, and proposed a extra austere scheme of three primary odour varieties: candy/ambrosiac, stench, and intermediate. One senses that ‘intermediate’ is doing plenty of work right here, however maybe Haller adopted the thought out of a conviction that every one odours could possibly be squeezed onto a line, and organised alongside a single axis. If these early odour taxonomies sound like they’ve a quite ad-hoc really feel to them, it’s as a result of they have been the fruit of introspection quite than cautious information assortment and measurement. Mainly, these guys have been winging it.

In equity although, it wasn’t (and truthfully nonetheless isn’t) actually apparent methods to not wing it. With all due deference to one among historical past’s geniuses, Newton had it simple. He might create primarily any seen color at will by rotating just a few items of polished glass in a slit of daylight. The stimulus simply confirmed up, unasked for, when the solar rose, and in a kind that was nearly readymade for scientific interrogation. Odours are far much less workable. If Newton had needed to review odour, he would have needed to begin by grabbing some vegetation, possibly some spoiled meals, a crust of bread, a swab from his chamber pot if he was feeling audacious and naughty. This doesn’t precisely scream ‘Newtonian’. The important lacking abstraction of ‘the chemical compound’ as the fundamental property-bearing token of odor was nonetheless far off, as have been the strategies for synthesising pure chemical substances for testing functions.

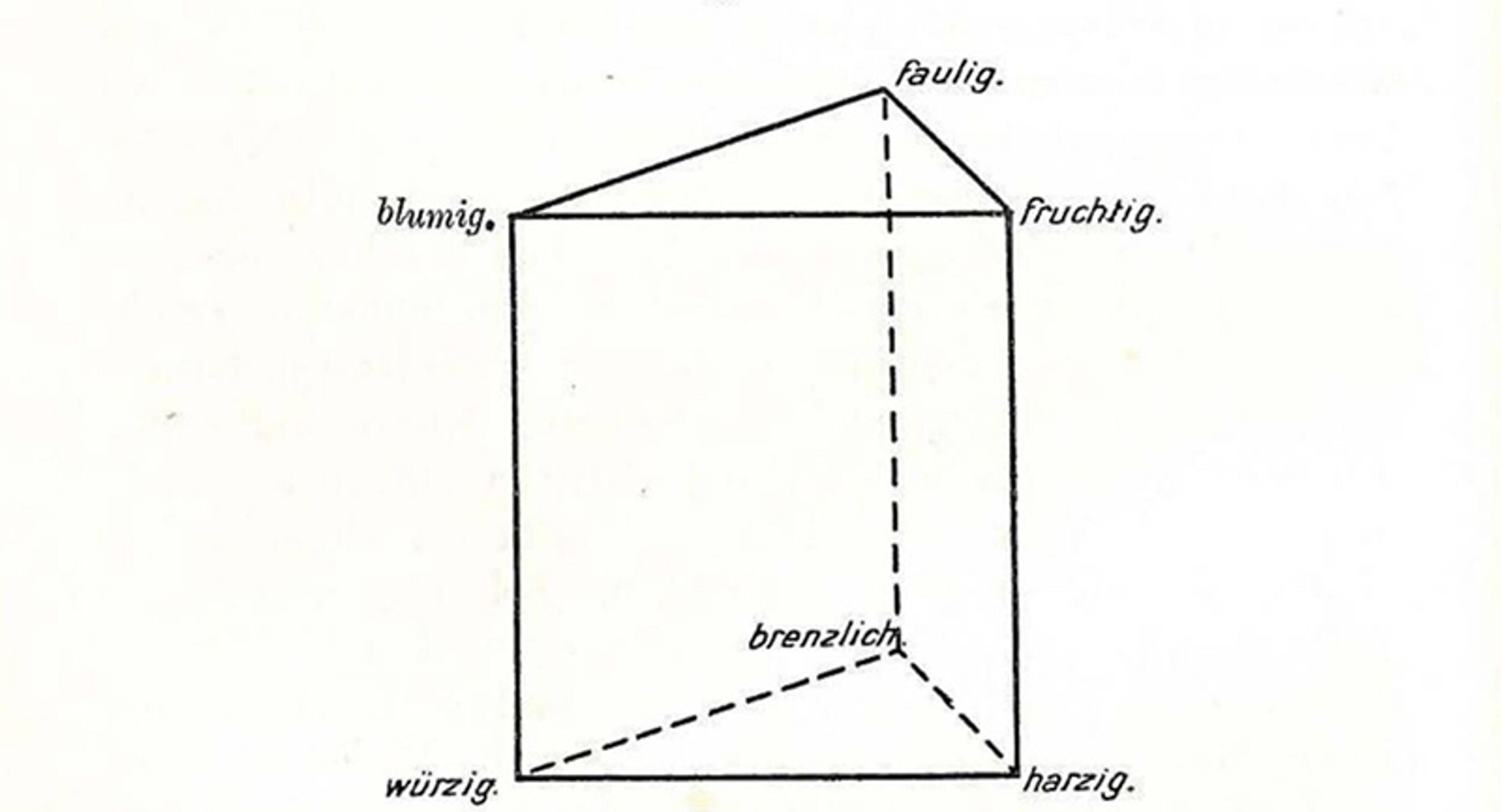

Henning proposed an odour prism that organised smells into flowery, fruity, resinous, spicy, burnt, and foul

However even when these impediments might have been, miraculously, handled, there are extra, deeper issues that make the issue of odor tougher than the issue of color. These boil right down to the truth that chemical substances aren’t easily graded variations of a single underlying phenomenon, like mild is. Relatively, they’re collections of the world’s particulate stuff. And, finally, there’s simply plenty of stuff and varieties of stuff on the market, making it extremely unlikely that some single chemical property – a molecular analogue of sunshine’s refrangibility – will seize all of the significant variability within the wild and woolly world of chemical substances. If there was a map from chemical options to odour qualities, it must contain one thing extra sophisticated than a circle, with extra locations – in actual fact, extra dimensions – to distribute the chemical substances.

Maybe one thing like a prism would do? If we take it as a unfastened geometric metaphor, it appears to have some virtues over the circle, and is reaching in the proper course. The prism has faces and aspects on totally different planes, which could possibly be used for organising molecules in accordance with various standards like atom kind or chemical group. Its sharp factors counsel areas of aggregation and separation in chemical house that emphasise odour’s discrete classes versus mild’s continua.

For the German scholar of odor Hans Henning, this was extra than simply metaphor. In his guide Der Geruch (‘Scent’) (1916), he proposed the thought of an summary odour prism that organised the world of smells, with its six pointy vertices equivalent to what he thought-about to be the olfactory primaries: flowery, fruity, resinous, spicy, burnt, and foul. Despite the fact that there had been appreciable developments that allowed for higher quantification of how people understand odour, and higher bodily descriptions of odour stimuli, the sector was not prepared for a proposal like Henning’s. He was, by all accounts, a type of scientists, described by the US neurobiologist Gordon Shepherd, ‘whose imaginations can not resist the temptation to place collectively an underconstrained idea.’ Additionally, Henning didn’t do himself any favours in forcefully selling his work, and swiping at influential icons of the sector just like the Dutch scientist Hendrik Zwaardemaker, who had pioneered using olfactometers – steam-punky contraptions of valves and tubing that delivered managed doses of odour. An early reviewer who in any other case spoke very positively of Henning’s guide nonetheless felt compelled to seek advice from him, on the file, as ‘a ruthless – in actual fact very uncivil – iconoclast.’ Henning had bulldozed into the dialogue a strongly geometric conception of odour that was impressed and influential however, finally, a home of playing cards.

To Henning’s credit score, regardless of his idea’s shakiness, it was particular sufficient to be testable, and the invitation was taken up by a number of, together with the psychologist Malcolm Macdonald. In a complete and devastating critique from 1922 that ended with an extended part entitled ‘Logical and Factual Inadequacies of Henning’s Principle’, Macdonald investigated whether or not there was actually a prism behind issues on the planet of smells. Utilizing judgments of relative odour similarity as a proxy for distance (the place ‘comparable smelling’ = ‘shut’), he carried out important perceptual reality-checks, like asking whether or not chemical substances taken from reverse ends of the lengthy prism diagonal smelled the least comparable. If you say that odour is a prism, it is best to anticipate that your colleagues will pull out their calculators and verify.

‘Odour maps’ gave a fowl’s eye view of how the human nostril organises the world of chemical substances

What, precisely, did Henning get incorrect? The query is a bit tongue-in-cheek, as a result of it’s not clear that there’s something he acquired proper. Nonetheless, if we need to be charitable, we’d say he was seduced by a Lego-like view of molecules that natural chemists have been growing on the time. They noticed a modular system through which natural molecules have been assembled from a small library of so-called purposeful teams, leading to motifs of some atoms organized in stereotyped methods. Along with haunting the desires of hopeful premeds in every single place, these purposeful teams have been thought to confer a molecule’s particular properties, and outline its primary reactivity. In Henning’s view, it was completely wise that the identical purposeful teams must also confer the first odours he had recognized. Certainly, there’s something attractive about the concept the chemist’s alphabet for natural molecules may additionally be the nostril’s alphabet for odor. In the end, nevertheless, nature selected to not oblige. Few olfactory neuroscientists would declare that purposeful group is unimportant for figuring out odour high quality, however it’s clearly not the entire story.

In trendy machine-learning parlance, we’d say that Henning didn’t have a wealthy sufficient function set for representing smells. In committing to purposeful group as his primary odor alphabet, he implicitly adopted a particular thought of what a molecule basically is, and discarded different probably helpful options that would function the grist for odour prediction. A molecule, in any case, isn’t only a checklist of the Lego blocks from which it’s made. It’s additionally a springy little factor that spins and vibrates, and chemists can ring it like a tiny molecular bell to hear for clues about its construction. It’s also a listing of descriptive attributes like ‘strongly acidic’, or ‘non-polar’ (having symmetrically distributed costs). And it’s additionally a lump of simply a lot stuff, possibly a bit bulkier right here, and extra stretched-out there.

As a substitute of doing what Henning did, seizing on one attribute upfront, the easiest way ahead is clearly an agnostic mindset the place the information does the speaking. As a substitute of constructing fantastically incorrect guesses about which chemical options decided odour high quality, why not winnow them down from a large checklist of all conceivable options?

That’s the strategy in research pioneered by the US scholar Susan Schiffman and others within the Seventies and ’80s. The fundamental thought was to take a set of some dozen odorous molecules and create a map summarising their relative perceptual similarities. Much like how one might create a tough map of the US from a desk of all (of the various!) between-city distances, these ‘odour maps’ gave a fowl’s eye view of how the human nostril organises the world of chemical substances. With this perceptual map in hand, the query then turned to chemistry: what’s it about molecules that assigns them to some explicit portion of the perceptual map? To get at this, Schiffman and others used a spread of ‘dimensionality discount’ strategies to see which chemical options – of the various tons of probably accessible – have been simplest at recapitulating the map. These approaches generated vital curiosity for a time, however they too have been unable to unravel the issue and went dormant for many years – till the age of AI.

It was in 2017 that information units have been lastly democratised sufficient for machine studying to assist scientists widen the search. An essential milestone that 12 months was the DREAM challenge to see who may clear up the odour map utilizing AI. Revealed in Science, the successful models have been endorsed by the neighborhood as potential inroads – suggesting that handing our model-making to the custody of the machines was the proper mental transfer.

One of the best fashions, the so-called ‘random forests’, used AI to mixture a bunch of fashions. The consequence could possibly be baroque and inscrutable programs of guidelines for performing prediction duties. They will get the proper reply, nevertheless it’s typically by discovering prolonged and sophisticated rubrics alongside the traces of: ‘If the molecular weight is > X, and the variety of carbons is > Y, and the Moreau-Broto autocorrelation of lag 7 is < Z, and…, and…, then the molecule will odor like rose.’

It’s after all attainable that odour categorisation is dealt with by comparable ‘brute’ computations within the mind, however one is left with the nagging query: is that actually how nature solved it? Not via the financial system of Occam’s razor however within the thicket of Occam’s forest? The place’s the deep precept? The fundamental organising axes? The geometric perception? An essential and often-asked query about these sorts of ‘data-driven’ fashions is whether or not their success at prediction really signifies understanding or, no less than, the sort of understanding that science has traditionally prized and glorified via tidy parables of discovery like ‘Newton and the prism’.

A method ahead is to surrender on the thought of an organised odour house whose curves and contours cleanly monitor some yet-to-be revealed chemical properties. In any case, if ‘smelly ft’ and ‘connoisseur cheese’ could be two legitimate descriptions of the identical bodily object, maybe odour qualities are simply too labile and particular person to essentially function the targets for prediction. Maybe they replicate extra what we’ve realized from residing within the messy world than something intrinsic to it, encoding our idiosyncratic experiences with, and predilections for, ft and cheeses. Maybe there’s even one thing romantic and price defending right here within the thought of a way that, many years into the age of mass digitisation, stays stubbornly phantom-like and evanescent, unmeasurable, and basically unavailable for seize by geometric ideas.

Scientists are coaching, tuning and tweaking million-parameter fashions that ingest digitised molecule after digitised molecule

Or we go in the wrong way. Hit the issue with much more information and extra computing energy. This was the large wager made by Osmo, a startup primarily based in Cambridge, Massachusetts that started a number of years in the past because the digital olfaction group at Google Mind, and which now has a number of dozen neuroscientists, chemists and laptop scientists on its workers.

Osmo is the brainchild of Alex Wiltschko, a Harvard-trained neurobiologist who made his mark in grad college growing pioneering computer-vision programs for analysing animal behaviour. After rising up in small-town Texas, the place, he drily notes ‘neither computer systems nor fragrance have been standard’, his twin passions for aromas and algorithms finally landed him on the helm of an organization that’s ‘giving computer systems a way of odor’.

That is about so far as one can get from Newton investigating the senses in his lonely parlour, sketching fashions on vellum with a quill pen. As a substitute, these scientists are collaborating to develop dense code repositories, coaching, tuning and tweaking million-parameter fashions that ingest digitised molecule after digitised molecule below the mandate This one smells like rose, this one smells like grass, determine methods to make that occur. The chemical substances should not given to the mannequin as lists of predetermined molecular properties which can be served as much as some homunculus chemist within the nostril. As a substitute, they’re represented as skeletal and stripped-down graphs that seize solely primary details about atom identities and their connectivity. The mannequin shouldn’t be looking for what points of recognized chemistry are essential for odor. It’s attempting to find whether or not chemical ideas we haven’t but considered might maintain the important thing for odor.

The Osmo mannequin is a kind of graphical ‘deep web’ that’s loosely impressed by the successive processing phases of the mind’s sensory programs. The analogy isn’t precise, nevertheless it’s just like how your mind captures uncooked data from the world and passes it downstream to items that can finally have one thing helpful or actionable to say concerning the inputs: ‘It’s a cat!’ or ‘Smells terrible!’ The output items are the doers and the deciders whose efficiency could be evaluated (‘Nope, it’s really a canine’ or ‘Yup, that chemical actually does odor terrible’), however many essential insights are discovered within the intermediate, or ‘hidden’, community layers, too. These could be regarded as a transformational house that squeezes and warps uncooked sensory inputs into sensory judgments. The connections between items that outline these transformations are realized regularly and incrementally by an AI system because it regularly iterates and self-adjusts primarily based on how properly it mimics human judgments. By peeking at these intermediate layers, we are able to get the insights of a latterday, AI-supercharged Newton of odor. They inform us how we’d take into consideration the house that chemical substances dwell in. Or no less than, as our nostril sees it.

So how can we get from the transformations inside the Osmo web to a literal geometry? The geometry at hand shouldn’t be a circle, or a prism, or any sort of easy archetypal form. As a substitute, it’s extra like a world of craggy chemical continents, every demarcating a conspicuous facet of human ecology, every seeming to ask a set of actions or appetites. There may be, for instance, a continent of ‘fermentation’, a ‘inexperienced’ continent, a land of the ‘meaty and savoury’. The important thing notion is that, on this house, two chemical substances are rendered as shut collectively and similar-smelling not as a result of they essentially share intrinsic structural options, however as a result of they share ecological roles and have a detailed and contingent relationship out within the wild, because it have been.

The Newtonian story of color house is about how human notion latches on to the world’s common and impersonal attributes (take into consideration mild’s wavelength and refrangibility). However the growing story of odor is about how our noses have decoded the world because it manifests regionally, relationally and idiosyncratically on our planet. Odour house, in different phrases, is framed in human-centred coordinates, reflecting our histories as foragers and hunters in a world that blooms and withers, with matter that ripens and decays. It’s a geometry that invests matter with its meanings and prospects for us.

But it surely’s not just a few loosely poetic house. Tapping the Osmo mannequin, one can compute distances and angles right here, predict which chemical will odor precisely midway in-between musk and carvone, look at whether or not a group of chemical substances ought to hint out a easy or squiggly path in odour-perceptual house. Furthermore, the Osmo mannequin does this demonstrably higher than different makes an attempt, suggesting that the best way it’s measuring distances between chemical substances might level to a deep precept of odour processing.

To odor one thing is to know the neighbourhood it lives in

Apparently, distances computed on the map correlate strongly with what has been termed ‘metabolic distance’ – roughly, how reachable one chemical is from one other via frequent metabolic pathways. If nature can simply transfer from chemical A to chemical B via a small variety of fermentation reactions, say, chances are high your nostril will discover A and B to odor alike, even when they lack apparent structural similarities. The essential corollary is that molecules with putting structural similarities needn’t odor alike (although, after all, they typically will). A and B may hypothetically differ by just one double bond, but when it’s a really costly double bond to kind or break, requiring numerous synthesis steps and chemical pirouettes, then the compounds will odor totally different to us. What the nostril appears to know shouldn’t be the static world of chemical substances, however the actions that nature makes via it.

A thinker would say that your nostril seems to be an empiricist – it classifies and categorises chemical substances on the premise of relationships that should be realized from the world both over evolutionary timescales or over a person’s lifetime. A mathematician, following up, would say that what’s realized is the summary, high-dimensional manifold that tracks the world’s chemical relationships – its partitioning into the branches, cycles and pathways that shuttle all over the world’s carbon. To odor one thing is to find it on this manifold, to know the neighbourhood it lives in.

These are nonetheless early days for theorising concerning the construction of odour house, however a number of investigators have put ahead the idea that the house is non-Euclidean, which means that it’s a far cry from the ‘intuitive’ geometry of secondary college, the place the angles of a triangle at all times add as much as 180 levels. As a substitute, odour house might have an intrinsic curvature to it (like a potato chip, in accordance with one theorist), pushed by the truth that distances in odour house are outlined much less just like the bodily distance between two individuals, and extra like their social distance.

Amazingly, Macdonald, the critic of Henning described above, had an instinct of this again in 1922, when he prompt modifications to the odour prism that amounted to changing it with a ‘hole hyper-solid with strong tetrahedrons as its sides’. That is tough to visualise however, mainly, it’s a higher-dimensional prism that offers odours more room through which they’ll distribute themselves. ‘There is no such thing as a purpose why psychological continua ought to happen solely below Euclidian [sic] limitations,’ he famous. Maybe odor has been the final standing sensory thriller as a result of its arithmetic has confirmed to be probably the most esoteric.