In a play printed in 1662, a playwright imagined a weird academic set-up for ladies. In a ‘feminine academy’ (additionally the identify of the play), younger ladies of ‘honourable Beginning’ and ‘historic descent’ are cloistered inside a home. Separated from the skin world – and with solely previous matrons to maintain them firm – they’re bordered by two grates, home windows into the open air which might be barred over. The ladies can be found to be checked out and listened to, however to not contact or be touched. On one facet, throngs of males stand round simply to see them. By the opposite grate, ladies collect in teams to hearken to their educated discourse.

It’s an odd set-up, comparable, in a method, to that of the medieval anchoress, enclosed from the world outdoors and largely forbidden from chatting with males, or anybody, past their partitions. And, just like the anchoresses of previous, these ladies devoted themselves to studying and studying, discussing all the pieces from ladies’s capability for wit, to the character of reality. The boys who stand round outdoors are able to discussing just one factor: their ‘minds are so filled with ideas of the Feminine Intercourse’, in order that they ‘haven’t any room for another topic.’ After all.

What’s going on on this play? Is it a picture of idealised feminine mental improvement? Possibly, however there’s a spanner within the works: the ladies being educated then use their eloquence to say that girls are incapable of knowledge, and that it’s nigh-on unattainable for a lady to acquit herself in public. Is it then a piece of misogyny, crafted by some Seventeenth-century woman-hating wit? Hardly. The ladies are involved with bettering themselves, of studying all the pieces they’ll, and the boys they fend off look like irredeemably silly.

May or not it’s a mannequin of an actual academic setting; the kind of education loved by its writer? The reply is, alas, nonetheless no. By the mid-Seventeenth century, the concept of a proper ladies’s training was starting to unfold – in the summertime of 1673, a college in Tottenham, north of London, marketed its capability to coach ‘gentlewomen’ – however, within the 1620s, when the play’s writer was born, there was no such luck. Ladies of a sure social class learnt solely the female necessities: learn how to sew, dance, and ‘prattle’.

With its imagined world, and irreconcilable contradictions, The Feminine Academy is an effective window into interested by its writer, Margaret Cavendish (1623-73): the poet, thinker, scientist, playwright, vogue pioneer, science fiction author and early feminist (her job titles might go on and on). Cavendish lived by way of a violent Civil Warfare, printed her poetry, prose and drama underneath her personal identify when to take action was all however remarkable for a lady, and have become one thing of an early fashionable superstar. She flits throughout pages and pages of sources from the interval, from Samuel Pepys’s scandalised diary entries (in a single entry, he huffs that ‘All of the town-talk is now-a-days of her extravagancies’) to letters about courtroom gossip. Within the 4 centuries after her delivery, approaches to her vacillate between idolising her look and performances (John Evelyn, the Seventeenth-century diarist, should have angered his spouse when he wrote repeatedly in his diary of how he couldn’t avoid Cavendish’s ‘extraordinary fanciful behavior, garb, and discourse’), and being fairly much less adoring. Virginia Woolf let the complete power of her insults fly at Cavendish, calling her ‘crack-brained and bird-witted’, a ‘large cucumber’, and a ‘bogey to frighten intelligent ladies with’. As late as 1979, a literary examine argued that Cavendish’s writing was proof of her ‘schizophrenia’.

Was Cavendish a feminist pioneer, or an eccentric dilettante? Early scientist, or ‘mad Madge’? And why, precisely, do opinions insist on various between such poles?

Born Margaret Lucas in 1623, her adolescence and training bear an odd resemblance to the ladies she imagined in The Feminine Academy, but not in the way in which that we’d count on. She had no thorough training by the hands of ‘grave matrons’ – no expectation to discourse on philosophical topics, and even to precise herself nicely – however was, as a substitute, instructed as the proper daughter of the rich, well-connected however not aristocratic courses. She learnt learn how to dance, and learn how to sing. What else might a lady want?

Her training was, nevertheless, like her imagined ladies in a technique. It was a lifetime of excessive seclusion. Within the giant nation home of St John’s Abbey in Colchester – constructed on former monastic land that had stated farewell to its non secular neighborhood after England’s Reformation – Margaret was curiously remoted. Because the youngest baby of a big household, she spent hours and hours alone. Her father had died shortly after her delivery, and her mom was a mannequin of sheltered widowhood, protecting herself and her household away from the society of Essex that surrounded them. A lot of Margaret’s elder brothers and sisters had already grown up and married. She was, for lengthy stretches of her childhood, virtually fully alone. She turned to imagined worlds for her firm, filling pages and pages of her ‘baby-books’ along with her sprawling, spidery handwriting. The siblings she did have round – a sister, at factors – stuffed her with nothing however anxiousness: she would pay attention for hours outdoors her door, simply checking to see if she might nonetheless hear her respiration.

Margaret’s mom and maybe Margaret herself had been paraded by way of city earlier than being imprisoned

Earlier than lengthy, Margaret’s childhood anxiousness would appear not neurotic nor misplaced however tragically prescient. By the summer season of 1642, it was clear that England was about to break down into critical civil disturbance, if not all-out civil conflict. The 11 years of Charles I’s private rule – the interval by which the king had ruled alone after the short-lived parliaments of 1628 and the escalating criticism of his insurance policies – had come to an finish in 1640. The king had been obliged to name the Brief Parliament (so known as as a result of it lasted solely three weeks) to attempt to fund the Bishops’ Wars in Scotland, wars that had begun after he had tried to reform the Church north of the border. The Brief Parliament was adopted by the Lengthy Parliament in the identical 12 months; Charles’s years of reigning alone had been over. And, quickly, his years of ruling in any respect would draw to a detailed: after an ill-fated try and arrest some notably rebellious MPs in January 1642, the king was compelled to retreat into exile because the skirmishes continued round him. Skirmishes grew to become battles, and battles grew to become wars and, in 1649, the king could be executed.

On this interval of disruption and divided loyalties, the Lucas household pinned their colors to the mast. They had been religious Royalists – supporters of Charles I – and in a growingly Puritan Colchester, this was an issue. By August 1642, Margaret’s brother John had begun to make preparations to ship horses and weapons to the king. The folks of Colchester observed, and stormed the home. Every little thing was ransacked, furnishings and bedding stolen, the household vault opened and the coffins stabbed by way of with swords. The ladies in the home – Margaret’s mom, and maybe Margaret herself – had been paraded by way of the city earlier than being imprisoned within the jail. It was terrifying, dramatic and momentous, however it quickly grew to become unremarkable: the same rampage was repeated not even six years later. This time, the marauding forces reduce the hair off Margaret’s lately deceased mom to put on as a wig.

In 1653, Londoners might wind their method over to the churchyard of St Paul’s Cathedral, which was much less an area of divine contemplation than a bustling market for distributors, a lot of them promoting books simply contemporary from the printers. In amongst this chaos of crowded outlets and stalls was the bookshop of the esteemed publishing duo John Martin and James Allestree. Below the papery piles of their works (non secular tracts, scientific pamphlets, political writings) was one thing fairly uncommon. Sitting in giant folio format was a e-book with the title Poems and Fancies. Upon opening, the reader could be greeted with all the pieces from rhyming couplets on the character of atoms, to verses on the existence of fairies.

One part of those poems was just a little completely different to the others, nevertheless. Away from the worlds of concept and creativeness, a number of the poems stayed nearer to dwelling. Only a few years after the preventing of the Civil Warfare had stopped, one of many poems returned to the battlefield, describing the our bodies of the troopers left behind:

Some, their legs cling dangling by the nervous strings,

And shoulders reduce, hung free, like flying wings.

Right here heads are cleft in two elements, brains lie mashed,

And all their faces into slices hashed.

The poet, Margaret Cavendish, might not have seen a lot of the battlefield up shut, however she had seen the ravages of the Civil Warfare attain her personal home. After the dysfunction of the early skirmishes had compelled its method into her childhood, she had entered the fray totally. She left her household – and her lifetime of secluded writing – to develop into one among Queen Henrietta Maria’s ladies-in-waiting. Henrietta Maria, the spouse of Charles I, was residing at Oxford with the exiled Royalists after months of driving across the nation trying to make sure the supply of weapons to them.

Cavendish hated courtroom. She had left her quiet life for one among infinite chatter however no extra curiosity. She detested the hours of gossip, sitting and ready, and extra gossip. She had no privateness, no time to retire or write. Years later, when she was reunited along with her pen, she would write a play about her expertise at courtroom known as The Presence. Her personal character, ‘Woman Bashful’, speaks no phrases on stage.

Terrifying sea journeys (and unlucky feminine travellers) grew to become a motif of Cavendish’s later writings

Throughout the pages of Poems and Fancies, there are extra clues about how Cavendish’s life took form because the Civil Warfare rumbled on. In a single poem, she likens a ‘younger Woman’ to a ship despatched into the ‘world’s sea’. Every little thing seems to be going nicely – ‘with winds of reward and wonder’s flowing tide’ – earlier than catastrophe strikes. Storms hit the boat (‘rebellious clouds foul black’), and the ship is pushed off-course, away from happiness and prosperity and into the ‘troubled seas of distress’.

In the summertime of 1644, Cavendish’s journey away from her dwelling and her household would take her a lot additional than Oxford. As one among her ladies-in-waiting, she had no alternative however to observe Queen Henrietta Maria when she determined to go away England. This was no simple alternative. Closely pregnant, and conscious that her Oxford base was much less safe because the Royalist forces suffered heavy losses within the north, the queen was extraordinarily susceptible. One parliamentarian basic, the Earl of Essex, had devised a plan to take advantage of the Royalist weak spot and supposed to seize her and, in so doing, power a faster finish to the conflict. For her personal security and the protection of the Royalist trigger, Henrietta Maria needed to depart her husband (she would by no means see him once more) and make plans to cross the Channel to France, her native nation and the place she nonetheless had household at courtroom. She gave delivery away from dwelling, left her child within the arms of a pal, and fled to the port in disguise. As soon as on board the ship, parliamentarian forces fired upon her. The queen upped the stakes: she instructed the captain that, if it appeared just like the boat was about to be captured, he was to explode the ship as a substitute. They escaped, however it’s no shock that terrifying sea journeys (and unlucky feminine travellers) grew to become a motif of Cavendish’s later writings.

However, if Poems and Fancies gives a semi-biographical gloss to Cavendish’s life – there are elegies for her brothers who died within the conflict, and a poem for her lifeless mom – how did it come to be printed in 1653, in Cromwell’s London, when Cavendish herself had left for exile some 9 years in the past? And the way did Cavendish come to have a e-book printed in any respect? Within the Seventeenth century, works by ladies reaching the printing press had been vanishingly few and much between. Between 1621 and 1625, solely eight works by ladies had been printed, an estimated 0.5 per cent of all books printed within the interval. Between 1651 to 1655 – the years by which Cavendish printed 4 volumes – 59 new works by ladies appeared; an estimated 1.3 per cent of whole publications. Even with this uptick in ladies’s writing, the overwhelming majority of those works by ladies had been on the ‘protected’ topics of maternal recommendation or faith. Ladies who didn’t keep inside these boundaries risked extra than simply not being learn; they could possibly be branded as improper, as scandalous, as one way or the other promiscuous for baring their phrases to the web page. Cavendish was a trend-setter, and an outlier.

As soon as once more, there’s a clue as to how this occurred in Cavendish’s extra private writing. In direction of the tip of her assortment, she describes a bride lined in jewels and gold assembly a bridegroom ‘dressed by honours advantageous’. The emphasis on the opulent finery might need been a poetic embellishment, however the marriage was not: in 1644 in Paris, Margaret married William Cavendish, then a marquis and later to develop into the primary Duke of Newcastle. Regardless of his title and his fame – he had been a Royalist commander on the ill-fated Battle of Marston Moor, which brought on his exile – the pair married in relative penury. The conflict had taken all the pieces from them. What it couldn’t take, although, was their minds. Previous to the conflict, William had been an mental patron – a pal of everybody from the thinker Thomas Hobbes to the playwright Ben Jonson. Throughout his exile, he nonetheless circulated with the philosophers René Descartes and Pierre Gassendi (on one event, Margaret even sat at dinner with each males). In marrying William, Margaret was marrying a world of academic alternatives, and a person with the connections – and social power – to make publication doable.

Lord Cavendish with His Spouse Margaret within the Backyard of Rubens in Antwerp (1662) by Gonzales Coques. Courtesy Wikipedia

Margaret and William spent the period of Cromwell’s Protectorate ensconced in Europe, in a home beforehand owned by the painter Peter Paul Rubens. They had been frequently laborious up. William’s household lands had been seized by the federal government and Margaret’s personal had been run to spoil. However she continued to write down, and to assume. After her first e-book was printed in 1653, she had written 10 extra by 1666. In 1660, she returned to England along with her husband. With Cromwell lifeless – and his physique exhumed and posthumously beheaded – the nation was protected for Royalists once more.

Cavendish is generally remembered for 3 issues: for being ‘mad’ (an accusation that has dogged her since an all-too-easily scandalised reader of her first e-book, one Dorothy Osborne, quipped that she had seen ‘soberer folks in Bedlam’), for sporting outrageous garments (she supposedly cavorted round London in a carriage pulled by eight white bulls, and wore attire reduce to beneath the extent of her nipples), and, fairly extra nebulously, for being the ‘mom of science fiction’.

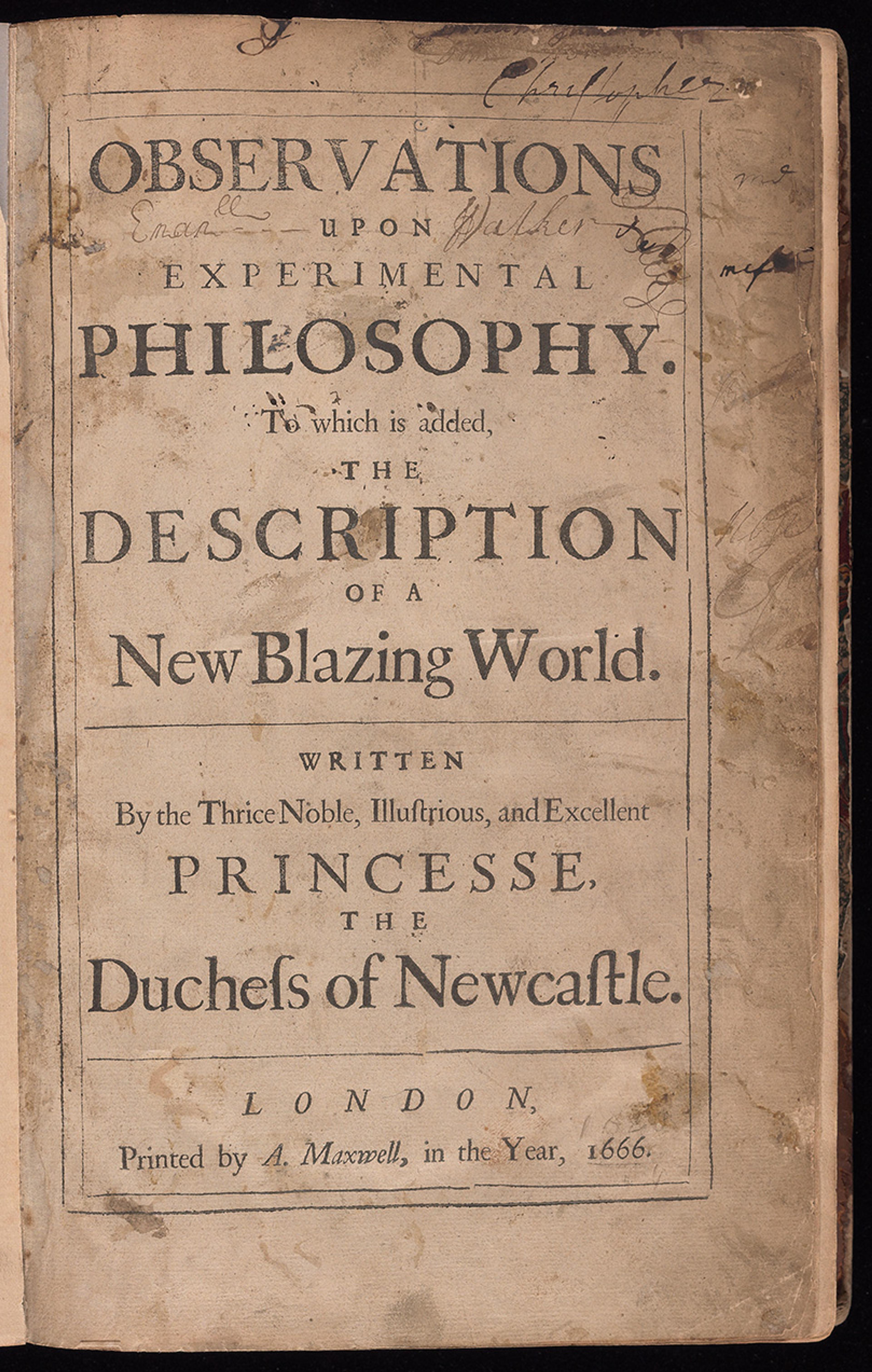

Printed in London in 1666. Courtesy the Beinecke Library, Yale University

What does this final designation imply? Science fiction is commonly regarded as a recent style born out of industrialism, innovations and highly effective machines. However Cavendish’s e-book The Blazing World (1666) – with its futuristic submarines in a parallel world, races of anthropomorphic human-animals, and flashy scientific experiments – is certainly an early work of science fiction.

She railed in opposition to the assumptions and presumptions of the boys of the Royal Society

In some ways, the e-book is an ideal summation of her concepts and her affect. The novel opens with a younger woman gathering seashells on a seaside when she is all of the sudden captured by a service provider. Simply as he thinks he’s the ‘happiest man of the world’, an almighty storm hits the boat, and whirls it uncontrolled and into the North Pole. The marauding service provider and his seamen die shortly within the excessive temperatures, however the woman is stored alive by the ‘mild of her magnificence’ and the ‘warmth of her youth’. She survives because the boat travels into a brand new world the place she is greeted by animal-human hybrids – lice-men, bear-men, fox-men – and will get married to the emperor. As empress of this world, she units about attempting to clarify and examine the land underneath her area, from the new deserts to the chilly ice; from the biggest animals all the way down to the smallest. The strategy she chooses for these investigations is, in fact, science. She offers all her topics a job: the bear-men are her experimental philosophers, the bird-men her astronomers, and the lice-men her mathematicians: all of them work beneath her, and the remainder of the e-book is a romp of descriptions of philosophical experiments, with microscopes and mathematical explanations, scientific debates and explorations of sapphic love. Right here, Cavendish was once more radical: her explorations of lesbianism – in her performs, and in The Blazing World – are uncommon for the Seventeenth century. Somewhat than being the bawdy, sticky imaginations of males, her description of girls’s relationships bears the hallmarks of reality and emotion. ‘However why might not I really like a Lady with the identical affection I might a Man?’ asks one among her characters in The Convent of Pleasure (1668).

The Blazing World is without doubt one of the earliest novels, a piece of science fiction, and the primary e-book to think about a complete new world. It’s additionally one among Cavendish’s philosophical and scientific texts, participating with debates over experimentation and cause that had been raging within the interval. When it was first printed in 1666, it was appended to her Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy – maybe Cavendish’s most fiery work of pure philosophy, by which she railed in opposition to the assumptions and presumptions of the boys of the Royal Society who claimed that all the pieces could possibly be found, and recognized, by way of the brand new frontiers of scientific experimentation. In our fashionable age, the place the scientific methodology is so carefully tied to empiricism, it may be laborious to take Cavendish’s qualms over experiments significantly. However she was writing and considering in an age that had seen the disruption wrought by the utopian beliefs of the Puritans through the Civil Warfare. Her scientific beliefs – anti-utopian; extra insistent on inner cause than exterior proof; and sceptical of claims to absolute, unbounded data – are deeply political.

The Blazing World can also be a feminist work – if we’re not squeamish about utilizing that time period to incorporate historic writing that considers ladies’s place in society, and the strictures they stay underneath. A younger woman is made empress of the entire world, she is rescued from terror (naturally, for Cavendish, a disastrous shipwreck) after which units about furthering herself intellectually. It’s no coincidence that directing all this cerebral endeavour is a lady.

What does Cavendish inform us about now? How is that this girl from the Seventeenth century related? Along with her boldness and her bravery in writing, Cavendish looks like a lady so out of her time, a lot nearer to our personal. And, when taken out of her context, she can be utilized as a determine to replicate so many points: ladies’s training, the denigration of girls’s writing, the issue of being taken significantly. Cavendish might, with little problem, develop into one thing of a feminist poster-girl; a lady so completely different to all of the others of her interval.

However there may be one other query. Isn’t she one way or the other reprehensible? She was a religious Royalist, in any case – a conservative, who upheld concepts a couple of inflexible, hierarchical social order that firmly put aristocrats (and monarchs) on the high, and everybody else on a descending scale. Cavendish noticed no contradiction between this and her radicalism elsewhere. For each second of her ‘right-on’ writing is a second of one thing fairly trickier. Is Cavendish too regressive, to terrible, to be paid consideration to now?

She additionally factors to a misplaced historical past: phrases that by no means met with the ink of a printing press

I’d prefer to recommend one thing past both of those potentialities. From The Blazing World to her numerous different works that talk to ladies’s place in Seventeenth-century society – performs about ladies retreating from the society of males; letters concerning the insufferable humiliation of childbirth – it turns into clear that Cavendish was not, really, an outlier. Her writing could also be part of a small share that was printed, however she was tied to a much wider custom of girls’s writing about ladies, about how their intercourse gave the impression to be topic to separate guidelines than for males.

Within the British Library, there’s a manuscript of the Fifteenth-century French-Italian poet Christine de Pizan. De Pizan wrote The Ebook of the Metropolis of Women which imagines a metropolis the place ladies could possibly be protected from males to pursue their very own goals. On the title web page is a doodle. There’s an opportunity it was carried out by Cavendish herself: she and William owned this precise copy. Cavendish is linked, too, to reams of different little-known ladies’s writing, from the letters of girls in her circle concerning the struggles of kid mortality, to the poems and performs written by her stepdaughters through the Civil Warfare. Somewhat than simply reflecting as we speak’s debates about ladies and girls’s writing, she additionally factors to a misplaced historical past: phrases that by no means met with the ink of a printing press, not like her personal successes.

Cavendish died in 1673, after publishing no fewer than 23 volumes. She achieved the unthinkable, in some ways. She printed, she wrote, she considered all the pieces – from theories of matter to the character of queens. She was taken significantly by some, and fewer significantly by others; she is revered in some circles now, and nonetheless denigrated in others. And it’s her contradictions that give her story life – her slippery, sensible problem – alongside her connection to a complete blazing world of girls’s phrases. Her epitaph in Westminster Abbey nonetheless speaks for her: she was a ‘clever wittie & discovered Woman, which her many Bookes do nicely testifie’.