Gustav Theodor Fechner championed the concept crops have souls – one thing we would name ‘consciousness’ immediately. I first realized of him in an interdisciplinary studying group on plant consciousness that I co-lead at Harvard College. We convene biologists, theologians, artists and ethologists to discover the burgeoning literature on vegetation. We discovered Fechner lined within the New York Instances bestselling ebook by Christopher Fowl and Peter Tompkins titled The Secret Lifetime of Crops (1973). Michael Pollan describes this ebook as a ‘beguiling mashup of legit plant science, quack experiments, and mystical nature worship that captured the general public creativeness at a time when New Age pondering was seeping into the mainstream.’ The Secret Lifetime of Crops cites Fechner as an essential however usually forgotten champion for plant sentience.

In 2006, 30 years after The Secret Lifetime of Crops, a daring group of scientists revealed an article calling to determine the sector of ‘plant neurobiology’ with the objective of ‘understanding how crops understand their circumstances and reply to environmental enter in an built-in vogue’. In different phrases, how crops may need one thing like minds.

The burgeoning subject of plant science has grow to be a wealthy playground for profound questions which have beguiled Western philosophy since Plato: particularly, what’s thoughts, the place does it prolong, and the way? Who has thoughts, and the way do we all know? Whereas scientists more and more agree that many animals are sentient, doubts stay about our vegetal kin. For a lot of, crops stay a restrict case within the forms of beings we’re keen to concede expertise life with the richness people do, or whose expertise we will meaningfully examine.

Fechner, writing greater than 150 years in the past, anticipated many claims of the modern plant neurobiology motion. His thought stands like an oasis amid an mental historical past in any other case hostile to crops. In any case, in De Anima, Aristotle deemed crops the bottom type of life, construing them as faulty animals. Francis Bacon later construed science as a way of torturing nature. And René Descartes not solely diminished animals to unthinking automata, however essentially ruptured the connection between matter and thoughts.

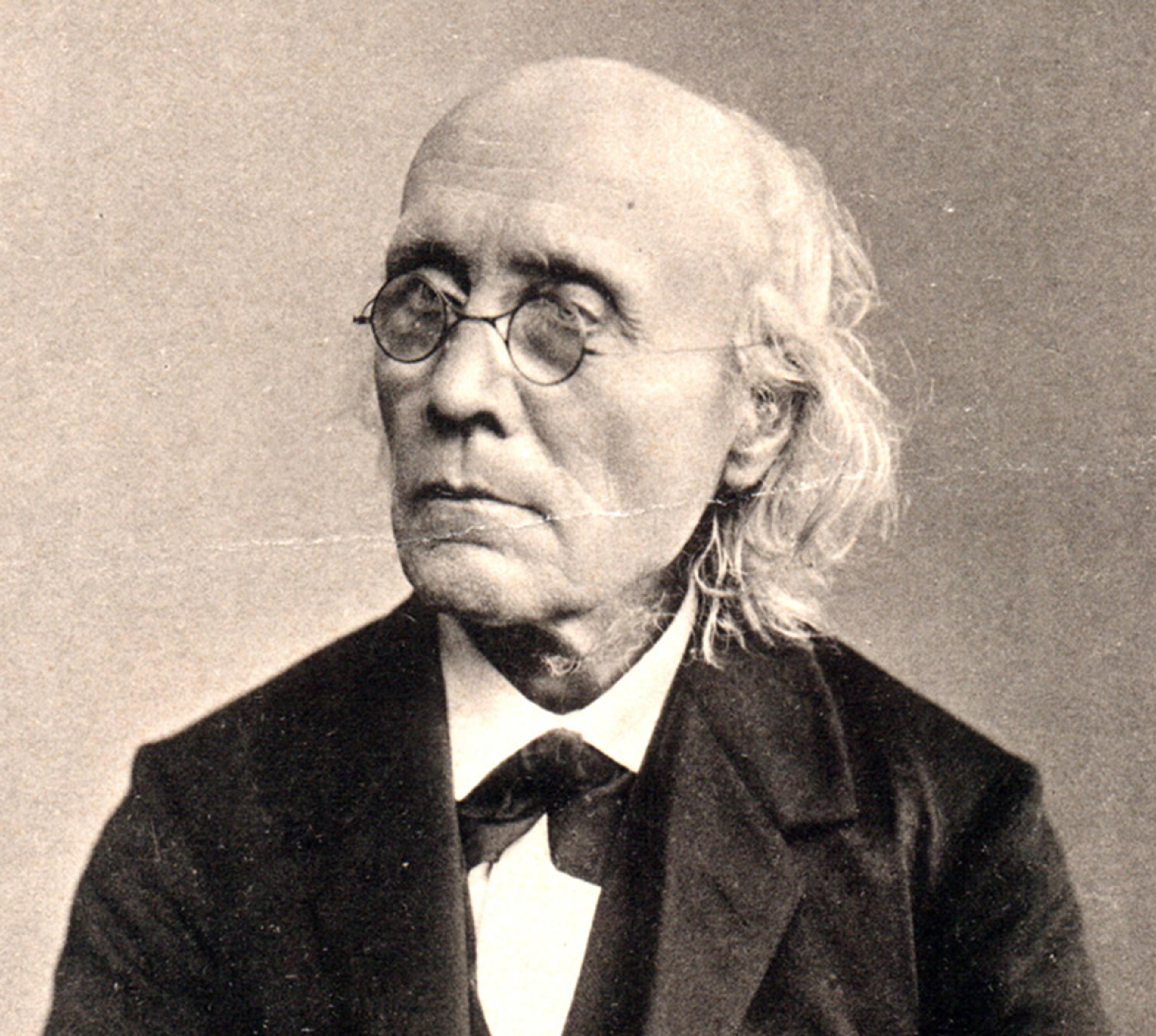

Fechner would spend his complete life attempting to heal the divide between thoughts and matter, and the commensurate break up between philosophy and science – however, first, he needed to go mad.

Fechner was born on 19 April 1801 in Groß Särchen, Saxony, the second baby of Samuel Traugott Fischer and Dorothea Fechner. Fechner’s father Samuel was a pastor, and likewise the primary individual within the village to vaccinate his youngsters. He put in a lightning rod on the church roof, and spoke Latin to his younger son. He died when Gustav was solely 5.

At 16, Fechner matriculated into the College of Leipzig as a medical pupil. ‘After my medical research,’ Fechner lamented, ‘I grew to become a whole atheist … I noticed solely a mechanical gear on the planet.’ Capitulating to this mechanical worldview, he deserted medication to review physics.

In February 1820, Fechner stumbled upon a replica of Grundriß der Naturphilosophie (1802) by Lorenz Oken, and ‘a brand new gentle out of the blue appeared to light up the entire world to me. I used to be blinded by it.’ The project of Naturphilosophie promised a fantastic unified worldview, one which struck Fechner with pressing necessity. Fechner couldn’t, nonetheless, disavow his love of measurements, experiments and equations. In contrast with physics, the sprawling top-down speculations of German idealism appeared inadequate. Rigorous systematicity was the ‘solely solution to obtain clear, dependable, and fruitful outcomes’. Fechner nonetheless longed to apprehend the invisible legal guidelines that triggered creation to ring in his ears like a symphony.

Displaying how mind stimulation affected bodily motion threatened to make notions of the ‘soul’ indefensible

When Fechner was born, Germany was nonetheless a philosophical powerhouse. Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Schelling and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe made the primary three a long time of the Nineteenth century among the most philosophically creative in fashionable historical past. After G W F Hegel died in 1831, main discoveries in biology, physiology and psychology laid the groundwork for an understanding of life in mathematical phrases. Because the empirical sciences grew in status and authority, Ludwig Feuerbach, Carl Vogt, Ludwig Büchner and different thinkers argued that each dwelling leaf, flower and fox could possibly be defined by appeals to the bodily and chemical properties of matter.

To some, Nineteenth-century advances in psychology appeared to make philosophy out of date. The brand new subject of psychology claimed to deal with the thoughts – that previous area of philosophy – in response to observational and more and more quantitative strategies. Anatomical experiments exhibiting how mind stimulation affected bodily motion threatened to make philosophical notions of the ‘soul’ indefensible.

Fechner embraced the requirements of fabric, empirical remark whilst he harboured a secret love of the dying Naturphilosophie. He studied physics with better depth, and he accepted a physics professorship in 1834 on the College of Leipzig, and lectured with out pay. To pay his payments, he translated multi-volume physics and chemistry works from French into German. Determined for work, the Latin-speaking doctor-turned-physicist discovered himself translating the eight-volume Hauslexikon, a Nineteenth-century equal of the Women’ House Journal, many 1000’s of pages lengthy. The tedium – the inanity – of Hauslexikon broke his spirit. Fechner labored himself into exhaustion. He was additionally going blind.

Impressed by Goethe’s examine of color, Fechner had carried out experiments into after-images by staring on the solar via tinted glasses. His sight broken, he retreated to a darkish room and tied a material blindfold over his eyes. And when he might tolerate the stress of the bandage not, a good friend crafted customized goggles with thick lead cups to cowl his eyes. He generally walked about his backyard, guided by his spouse, with two black bulbs protruding from his sunken face. Pacing up and down rows of lilies and lilacs, maybe he seemed like a crazed, metallic bug.

The disaster lasted from December 1839 to October 1843. Docs handled him with therapies of the day – magnetism, vapours, electrical energy – to little success. The episode, which we would immediately characterise as melancholy, neurotic obsession and mania, would radically alter Fechner’s life. By 1843, the person who was as soon as a voracious learner couldn’t learn.

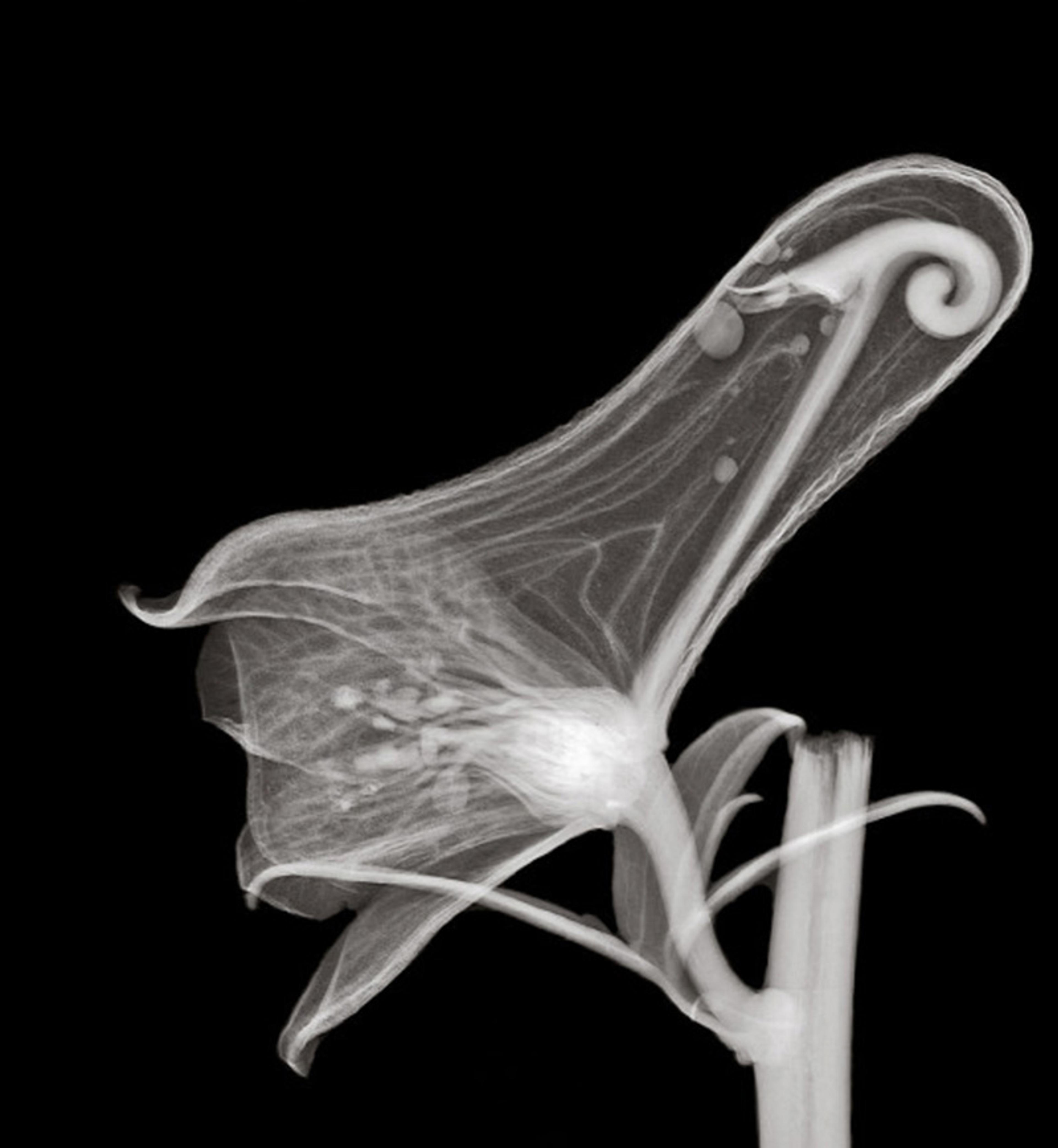

Fechner healed – slowly at first, then . He cites a number of components: the caring devotion of his spouse, in addition to spiritual ideas, lengthy dormant, that reemerged throughout this time. Probably the most important second of Fechner’s restoration occurred on 5 October 1843, when he stepped out from his darkened room into his backyard for the primary time with out his eye cowl. He out of the blue caught ‘a stupendous glimpse past the boundary of human expertise. Each flower shone in direction of me with a peculiar readability, as if it had been throwing its inside gentle outwards.’ The entire backyard was transfigured. And he thought to himself: ‘one should solely open one’s eyes afresh to see nature, as soon as stale, alive once more.’

In 1846, at his first public lecture in six years, Fechner declared that his sickness had ushered in a ‘larger calling’ of considering ‘inside nature’. He had crossed the bridge between inside and outer, to a spot the place the boundary between seen and invisible loses its which means. Plant souls had rooted in Fechner; he wished to allow them to bloom and flower on the web page, to exempt not even the tiniest weed. He would spend the remainder of his life inviting readers to cross over, and think about nature with new eyes.

Impressed by his imaginative and prescient, he wrote Nanna oder über das Seelenleben der Pflanzen (‘Nanna, or On the Soul Lifetime of Crops’), revealed in 1848. The ebook attracts from cutting-edge botanical experiments by Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, Matthias Jakob Schleiden, Hugo von Mohl and others, in addition to Fechner’s personal shut remark of crops. In Nanna (named after the Norse goddess of flowers), Fechner argues that crops are aware beings with emotions and needs. They delight within the solar as we would enjoyment of a healthful meal. The world strikes crops with pleasure, ache, and even which means.

Nanna asserts that we will solely ever infer the existence of inside expertise via outward bodily expressions. And though we can not absolutely know nature from inside – eg, we will by no means get contained in the thoughts of a plant – we will get shut via comparability. We do that on a regular basis, Fechner says. We assume some shared inside expertise after we gaze into the eyes of a lover, mother or father, good friend or foe: ‘My conclusion that you just, my good friend, have a thoughts is based ultimately upon the truth that your outward look, your speech, and your behaviour are analogous to mine.’ In case you are like me, you need to have a soul like me.

To those that say crops don’t transfer, Fechner says that we merely lack the endurance to watch their slowness

The inherent interiority of issues requires an infinite technique of approximation. For that reason, Fechner’s most popular rhetorical technique is analogy. Fechner addresses the objection – widespread then as now – that crops can not have a thoughts as a result of they lack a nervous system. He contends that crops possess one thing analogous to animals’ nervous methods, constituted by plant fibres and filaments. However he additionally questions why crops couldn’t have subjective sensations with out nerves. Why grant the nervous system an distinctive standing on the subject of the soul? Nature seeks various means to realize comparable ends. The violin, for instance, requires strings to intone. We’d think about the strings as nerves. However one would then conclude {that a} flute or trombone makes no sound as a result of it lacks strings. Animals would possibly simply be the ‘string devices of sensation, and the crops the wind devices’.

Analogies are by no means excellent. In the event that they needed to be, Fechner acknowledged, we might deny subjectivity to ‘each one that doesn’t appear to be me or behaves otherwise’. For Fechner, the place analogies fall brief, they instruct. That is maybe Fechner’s most exceptional attribute: his epistemological humility converts right into a form of ontological generosity. To those that say crops don’t transfer, Fechner says (as Charles Darwin did) that we merely lack the endurance to watch their slowness. To those that say crops lack speech, Fechner holds forth on a lexicon of perfume, scent poured from chalice to chalice like nice gossipy chatter:

Along with the souls which run about and cry and feast would possibly there not be souls that bloom in stillness, that quench thirst by slurping dew, that exhale perfume, that fulfill their highest longings by budding and burgeoning in direction of gentle?

So, that crops differ from people and animals in construction and performance doesn’t show they lack souls. Quite, they’re otherwise ensouled.

Fechner imagines that crops might apply their very own soul standards to people and discover us missing. Crops could assume, primarily based on their very own expertise, that the soul is evidenced by a capability to self-generate and self-adorn, to create one’s physique leaf by leaf. However people should ‘depart our physique as it’s’ and don exterior clothes. As well as, the plant is sessile; we run about. ‘The oak,’ he writes, ‘might simply flip our arguments towards her soul again towards ours.’ To crops, we should look very soulless.

To Fechner, a soul is one thing with an interiority, a subjective consciousness – an ‘inward luminosity similar to the outward luminosity which is obvious in its physique’. Tellingly, Fechner usually makes use of soul (Seele) and thoughts (Geist) interchangeably as belonging to a being that experiences emotions (Empfindungen), together with inside urges (Triebe) and exterior stimuli (Reize); instinct (Anschauung) and emotion (Gefühl). Forged in fashionable phrases, we would merely say a soul is the capability for subjective expertise – what some cognitive scientists name main or phenomenal consciousness. For Fechner, there may be, as Thomas Nagel put it, ‘one thing it’s like’ to be a plant.

For Fechner, a soul by no means exists impartial of a physique. Bodily type is the outward, wise facet of the soul, and the soul is the inward expertise of type. In impact, physique and soul are the identical factor, seen from completely different views.

The modern thinker of thoughts Peter Godfrey-Smith depends on experimental proof to find out which creatures are aware. Proof has satisfied Godfrey-Smith that octopuses, canine and, extra just lately, bees have subjective experiences of actuality, or what Fechner may need known as soul.

Whereas lecturing at Harvard, Godfrey-Smith cited a current experiment that subjected octopuses to ache and concluded that it damage them. In different phrases, there may be ‘one thing that it’s like’ to be a wounded octopus. Through the Q&A, a girl raised her hand. ‘I’m nonetheless confused as to how that experiment proves something in any respect,’ she mentioned. ‘I suppose, I simply need extra. How do we all know the octopus feels ache? How can we make sure something is happening in there?’ With a kindness that recommended familiarity with this objection, Godfrey-Smith replied, ‘nicely, I think about you’ll really feel glad with the proof if members of this viewers, or your folks or relations, had been topic to the identical experiment.’

The reductive materialism that launched throughout Fechner’s life continues its ascent and has lengthy weakened our urge for food to say something like a soul. The prevailing scientific view is that consciousness emerges from complicated networks of neurons – in different phrases, the thoughts is what the mind does. Consciousness is a property of neuronal visitors or maybe even refined computer code.

In The Declare of Motive (1979), his sweeping ebook on Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stanley Cavell supplies a prognosis of scepticism: how can we actually know what’s occurring within the minds of others? How can we all know that what seems actual is actual in any respect? Growing experimental proof ‘proves’ that extra animals fulfill scientific standards for consciousness, and it’s the vegetal kingdom that’s turning into the stage on which scepticism performs out.

The incessant quest to know sidesteps the precise world, the actual lives of others earlier than us, radiant, ready to be seen

Cavell treats scepticism as a situation we reckon with, both productively or at nice value to ourselves and others. Scepticism, for Cavell, expresses a discomfort with the finitude of life, and a resistance to accepting the world and acknowledging these with whom we share it. Bereft of transcendent absolutes, people usually attain to motive for the reply. We convert an ontological drawback into an epistemological one. When motive fails to ship actuality, we disavow ourselves of that actuality.

The result’s what Cavell calls ‘soul-blindness’, a situation wherein the sceptic ‘lack[s] the capability to see human beings as human beings’. This blindness, he implies, is rooted in our incapability to embrace exteriority as enough proof of wealthy interiority: ‘to not imagine there may be such a factor because the human soul is to not know what the human physique is,’ wrote Cavell.

Fechner would possibly reply: to not imagine there may be such a factor as a human soul is to not know what the plant physique is. And to not imagine there may be such a factor as a plant soul is to not know what the human physique is. On this approach, soul-blindness could also be inherently associated to a widespread phenomenon that scientists term ‘plant-blindness’ – an incapability of people to see or discover crops within the setting.

Cavell’s work is among the most compelling in illuminating the tragic implications of scepticism on the lifetime of the sceptic. Within the essay ‘The Avoidance of Love’ (1969), Cavell argues that scepticism drives the occasions in Shakespeare’s King Lear. He understands Lear’s incapability to acknowledge what he already is aware of – that Cordelia loves him – as his incapability to simply accept the human situation. Lear, just like the sceptical epistemologist looking for sure data, loses the very presence he craves. The incessant quest to know sidesteps the precise world, the actual lives of others earlier than us, radiant, ready to be seen – winged, leafed, loving, destitute. Ultimately, the sceptic – like Gloucester in King Lear, like Fechner in a darkish room – finally ends up eyeless, with out direct entry to the world.

The biologist E O Wilson characterised our present epoch of ecological extinction because the Eremocene – or age of loneliness. I used to assume he meant solely the melancholy that accompanies silence the place there must be birdsong. How might we not really feel lonely as our metastasising metropoles, branching roads and industrial agriculture kill off species at an unprecedented fee? However possibly our species loneliness has as a lot to do with soul-blindness as our land-use insurance policies. Scepticism fills Earth with mewing, howling, slithering ghosts – shadows of refused gentle. We ‘have misplaced … some image of what understanding one other, or being identified by one other, would actually come to,’ says Cavell, ‘a concord, a harmony, a union, a transparence, a governance, an influence – towards which our precise successes at understanding, and being identified, are poor issues.’

The tragedy of our occasions is the tragedy of Lear, says Cavell: ‘we might relatively homicide the world than allow it to show us to vary.’

Many of the factors Fechner makes in Nanna are actually being made once more, albeit with completely different proof, by modern plant neurobiology researchers. Like Fechner, these scientists reject a fetishisation of neurons (regardless of their title). They stick with it his declare that crops possess one thing analogous to animal brains – although, in contrast to Fechner, they usually attempt to establish molecular-level purposeful similarities between animal and plant substrates. Like Fechner, they argue that plant behaviour is clever – ‘adaptive, versatile, anticipatory, and goal-oriented’ – relatively than merely hardwired intuition, as evidenced by experiments that doc plant studying, kin recognition, communication. A number of scientists who help the cognitive capability of crops additionally maintain out the chance that they’re sentient – what Fechner known as ensouled (beseelt).

A professor as soon as remarked with a smirk to Fechner’s nephew: in case your uncle is so severe about his argument in Nanna, he should additionally, to be constant, prolong ensoulment to stars. Actually, in his later three-volume treatise Zend-Avesta (1851), Fechner provides Nanna a cosmic improve, extending his analogical reasoning to celestial our bodies. Couldn’t Earth be mentioned to behave, in some methods, just like the human physique? Might it even have a soul? All of creation harboured an interiority, a wealthy sensuous life, a form of freedom. And people comprise, partly, this terrestrial consciousness. We rise upon the planet as wavelets rise upon the ocean. We develop out of her soil as leaves develop from a tree. We’re the sense organs of Earth’s soul: when one in all us dies, ‘it’s as if an eye fixed of the world had been closed,’ as William James mentioned in a lecture regarding Fechner’s thought. Zend-Avesta regards exterior creation (nature) and inside life (souls) as two facets of the identical actuality. All matter and spirit co-occur, co-instantiate, and can’t be separated.

In the present day, plant scientists who endorse the potential for plant sentience face important criticism

Panpsychism, which holds that each one issues have a thoughts or mind-like high quality, is an historic concept. And, in some ways, Fechner was a panpsychist, or maybe a pantheist. For Fechner, ‘perception within the plant soul is just a bit occasion’ of broader questions concerning the animacy of the more-than-human world. Whereas it might be tough to think about mountains, rivers and stars as aware – as Fechner later would – he noticed crops as an accessible entry level into broader notions of thoughts. He in contrast considering plant souls to a graspable pot deal with:

Simply as a giant pot might be grasped extra simply by its little deal with than by its giant stomach, so I thought-about that within the little soul of the plant I had discovered somewhat deal with by which religion within the best issues could possibly be extra simply hoisted to the pedestal.

Fechner’s later books flopped. None noticed a second version, and so they stay untranslated. Colleagues dismissed Fechner’s daring philosophy as a product of a thoughts gone wild, whilst they lauded his earlier scientific work. Fechner bemoaned that ‘if they need to settle for different writings of mine, reminiscent of atomic concept and psychophysics, … it appears that evidently they make two beings of me, of which they deem just one worthy of consideration.’

The US psychologist William James was one in all Fechner’s few champions. James rhapsodised about Fechner:

The unique sin, in response to Fechner, of each our widespread and our scientific pondering, is our inveterate behavior of concerning the non secular not because the rule however as an exception within the midst of nature.

James thought Fechner provided a corrective view, one that may ‘wield an increasing number of affect as time goes on’. In the present day, plant scientists who endorse the potential for plant sentience face important criticism. In a 2021 article within the journal Protoplasma, critics known as it ‘regrettable’ that ‘claims [by scientists] that crops have aware experiences’ are ‘discovering their approach into respectable scientific journals – even top-tier journals’, which could ‘generate mistaken concepts concerning the plant sciences in younger, aspiring plant biologists’. These claims are ‘deceptive and have the potential to misdirect funding and governmental coverage selections.’ One wonders what hurt they assume granting crops minds would possibly trigger – and whether it is by some means extra extreme than the reverse.

Even immediately, as Fechner lamented, ‘individuals discover the pot too large, and the deal with too little, and go on cooking in the identical previous pot.’

In 1848, when Fechner’s Nanna was revealed, a fantastic darkness fell throughout Europe. Revolutions unfold. Germans fled on boats – fled with their households and few belongings to Galveston, to Cincinnati, to Milwaukee. Fechner knew: to speak about plant souls at a time like that risked irrelevance at greatest, impudence at worst. In brief: who cared?

He begins the ebook with an apology:

I confess that I’ve had some misgivings about elevating the topic I’m about to lift these days … How might I demand you start to listen to the whisper of flowers, by no means heard earlier than even in quiet occasions, now that roaring winds threaten to topple even deeply rooted trunks??

Wars, a worldwide pandemic, the local weather disaster, the specter of AI, inflation, and the crushing heap of our bodies – human and in any other case – murdered within the title of hate, conquest, greed. However possibly meaning a brand new imaginative and prescient is required now greater than ever. Possibly we should grip the pot with no matter small deal with we will.

Of the failure of his books, Fechner expressed unhappiness however not fear. He wrote in his diary: ‘The approaching period will do justice to concepts that don’t match into the current, or the present does not match.’

Fechner reminds us that rigorous, scientific pondering needn’t be pitted towards daring metaphysical claims. He provides a solution to attend to thriller with out renouncing matter, and the inverse. Maybe most of all, his life serves as a reminder that soul-blindness, and its attendant plant-blindness, carries dangers. He jogs my memory that one of the simplest ways to apprehend the unseen in crops is to take off the blindfold and look. He jogs my memory that what we stand to achieve by nature with new eyes is nothing wanting the world, and nothing wanting one another.