‘I’ve a horrible worry that I shall at some point be pronounced holy …’

– from Ecce Homo (1888/1908) by Friedrich Nietzsche

On the morning of 24 September 1938, a Franciscan priest by the title of Herman Van Breda arrived on the Belgian Embassy in Berlin, Germany, carrying three giant, overstuffed suitcases. He had an appointment with Viscount J Berryer, the secretary to the Belgian ambassador. They met at 11am, and Van Breda handed over the suitcases, with Berryer assuring him they’d be despatched excessive safety to Belgium, and wouldn’t be investigated by the German authorities, in accordance with worldwide guidelines on diplomatic paperwork.

These had been no atypical papers, nevertheless. The suitcases contained the archives of the nice German thinker Edmund Husserl.

Husserl, the founding father of phenomenology, had died 5 months earlier. As soon as one of many preeminent cultural voices in German philosophy, his final years had seen him lose his professorship, his entry to the College of Freiburg, and lots of of his pals, together with his friendship to his closest scholar, Martin Heidegger. Regardless of having transformed to the Lutheran Church 50 years earlier, Husserl was born Jewish, and the racial legal guidelines introduced in by the Nationwide Socialists in 1933 had seen his life, like so many others, destroyed.

Outside Germany, Husserl’s fame and esteem remained excessive, and Father Van Breda had studied his work on the Catholic College of Louvain in Belgium. Van Breda travelled to Freiburg as a way to research and catalogue Husserl’s unpublished writings, which the thinker had typically talked about in his printed books. These had been now not held on the college however had been eliminated by Husserl’s college students and by his widow, Malvine, and brought to their home.

Herman van Breda. Courtesy Wikipedia

Van Breda was astonished to seek out some 40,000 pages of stenographic materials that had been handwritten by Husserl, in addition to round 10,000 pages of typed or handwritten transcriptions. All had been at risk – the Nazi authorities had begun their programme of burning ‘degenerate’ (typically merely that means ‘Jewish’) artwork and literature and, ought to the archive fall into their palms, its destruction was inevitable.

Initially, Van Breda tried to get the papers overseas by enlisting the assistance of nuns – he took the papers to a convent in Konstantz, which bordered Switzerland, with the concept that the sisters might carry them to security a couple of at a time. Nevertheless it quickly grew to become clear that this was too harmful and, ought to the border be closed midway via the operation, the papers can be cut up up, maybe eternally. So Van Breda took them again and deposited them in a monastery in Berlin-Pankow – a dangerous transfer as monasteries had been now being searched.

Many French philosophers have began their careers by exploring the Husserl Archive. All due to the bravery of 1 Belgian priest

It was then he come across the thought of sending them through diplomatic channels, and shortly after he met with Viscount Berryer. He left the handwritten originals with him – and the Belgian diplomat managed to get them to security – whereas Van Breda positioned the works that had been transcribed by Husserl’s assistants in his personal baggage for the return to Louvain. Mercifully, his suitcase remained unopened by authorities.

Van Breda would spend the remainder of his life establishing and serving to to curate the Husserl Archive, overseeing the transcription of your entire physique of labor by Husserl’s assistants. It has turn out to be one of the necessary philosophical archives on the earth, and lots of French philosophers have began their careers by exploring it and utilizing the works as jumping-off factors – together with Jacques Derrida, Paul Ricoeur and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. All due to the bravery of 1 Belgian priest.

To enter the Husserl Archive now’s an act of homage: listed, catalogued, cross-referenced, translated – the fragments have the texture of a cohesive complete. They’re housed in a brightly lit, ethereal library, and it’s tough to reconcile the present destiny of the papers with these stuffed suitcases. Now a analysis institute for phenomenology, with cheerful and useful employees, in a position in moments to put earlier than you a tiny slip of paper that one gust of wind or one Nazi following orders may need in any other case consigned to everlasting oblivion.

This reveals one of many important traits of an archive. To be an archive, the fabric should be public – there isn’t a such factor as a non-public archive. It’s situated in area, an area outdoors the individual whom it historicises. On this method, an archive is all the time threatened with destruction, and with it the individual or time commemorated. Totalitarian governments of all stripes have recognised this – for all of the defiance of the Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov’s phrase ‘manuscripts don’t burn’ – they do, and with them are immolated lives, methods of being, and cultures.

So, for the customer to the Husserl Archive in Louvain (aka Leuven), whether or not they’re there to check, or merely to browse, nevertheless gentle and ethereal the surrounds, to come across the papers Husserl wrote on, discovered with, and touched, is to come across a possible dying, and to see how skinny the road is between existence and nonexistence.

What is an archive? Particularly, what’s an archive when it’s of a author, thinker or different thinker? Definitely, it could be anticipated to include their printed works – these are, in any case, for public consumption, they’re written with the thought of an viewers in thoughts. However what of the remainder? As is well-known, what’s printed is commonly removed from all of a specific thinker’s work – there are letters and diaries, first (and one hundred and first!) drafts of poems, novels, philosophical papers. There are marginalia – notes written by nice thinkers within the margins of different writers’ works (the poet Lord Byron’s notes within the margins of Isaac D’Israeli’s Literary Character of Males of Genius are much more well-known than the e-book itself).

There are additionally writings much less straightforward to classify: notes to self, notes to others, notes to who is aware of who, procuring lists, and simply notes that, whereas written within the author’s hand, stay baffling to future researchers. Ought to these be a part of the archive too? The place does one draw the boundary?

Some writers have been notoriously brutal in coping with their unpublished scribblings – Marcel Proust was very happy to see the 1.3 million phrases that make up his À la recherche du temps perdu (1913-27) be printed, however he insisted on his notebooks being burnt.

To promote or present one’s archive is a method of not solely holding on to posterity however shaping one’s (posthumous) picture

The Czech writer Franz Kafka went additional, asking his buddy Max Brod to burn all the things he had written when he died. Brod selected to not – had he, Kafka would have been misplaced to historical past. In actual fact, an entire Kafka business has grown up round him, in order that we now know in microscopic element in regards to the life of 1 who wished to be forgotten – a state of affairs satirised by Alan Bennett in his play Kafka’s Dick (1986), wherein the author comes again to seek out that even the dimensions of his member isn’t solely identified, however the topic of scrutiny by cultural theorists.

Different writers are extra comfy with – or certainly encourage – their archive being saved, saved and assessed. Universities and museums construct holdings of the works of nice writers, as a useful resource for research. To promote or present one’s archive – letters, drafts, notebooks, these days even laptops – to an establishment is seen as a method of not solely holding on to posterity however shaping one’s (posthumous) picture. In lots of circumstances, the ‘unedited variations’ of the literary self are as finely edited as these written overtly for the general public area.

Thus, as Derrida has argued, creating an archive isn’t merely a literary (or philosophical) act however a political one. What’s included and excluded from an archive is a strategy to pin the butterfly of a author’s oeuvre, presenting them in a specific method, and presumably to a specific finish.

One of probably the most well-known circumstances of that is what occurred to the archive of one other German thinker, Friedrich Nietzsche. Born in 1844, he stays one of the controversial thinkers of all time, calling for nothing lower than ‘a re-evaluation of all values’. All morality, Nietzsche argues, is socially constructed, and has no foundation in ‘fact’. Worse, typical Western morality, constructed round Christianity, is the morality of what he referred to as ‘slaves’, somewhat than of wholesome human beings. It was not for nothing that he declared: ‘I’m no man, I’m dynamite.’

Friedrich Nietzsche painted in 1894 by Curt Stoeving. Courtesy Klassik Stiftung Weimar

All the time suffering from dangerous well being, together with piercing migraines and presumably syphilis, Nietzsche suffered a psychological breakdown in 1889, shortly after his forty fourth birthday. He would spend the final 11 years of his life being nursed, first in an asylum, then by his mom, and at last by his youthful sister Elisabeth, who in 1897 took him in at her house Villa Silberblick in Weimar, and who additionally took management of his archive. It was to be a momentous determination.

Friedrich and Elisabeth had been shut all through their lives, however this modified in 1885 when she married Bernhard Förster. Förster was a number one determine in Germany’s far Proper, and a distinguished antisemite who described Jews as ‘a parasite on the German physique’. He and Elisabeth arrange an ‘superb neighborhood’ in Paraguay, which they referred to as Nueva Germania – New Germany – the place they put into follow their ‘utopian’ concepts in regards to the superiority of the Aryan race. Of their beliefs, they had been the type of proto-Nazis to whom Hitler would attraction quickly after.

She made her brother’s work not merely palatable to far-Proper readers, however a piece of advocacy for them

The failure of this neighborhood – most of those ‘superior beings’ had been unable to deal with the cruel atmosphere wherein they discovered themselves, and died of hunger and illness – led to Förster’s suicide in 1889. Elisabeth continued to run the colony till 1893, returning to seek out her brother now not sane.

By then, having bought barely any books in his lifetime, Nietzsche’s fame – unbeknown to him – had begun to develop. His printed works had been starting to return again into print, and Elisabeth had entry to an enormous retailer of unpublished work. This she set about curating – transcribing it, enhancing it, and placing it into some type of cohesive order.

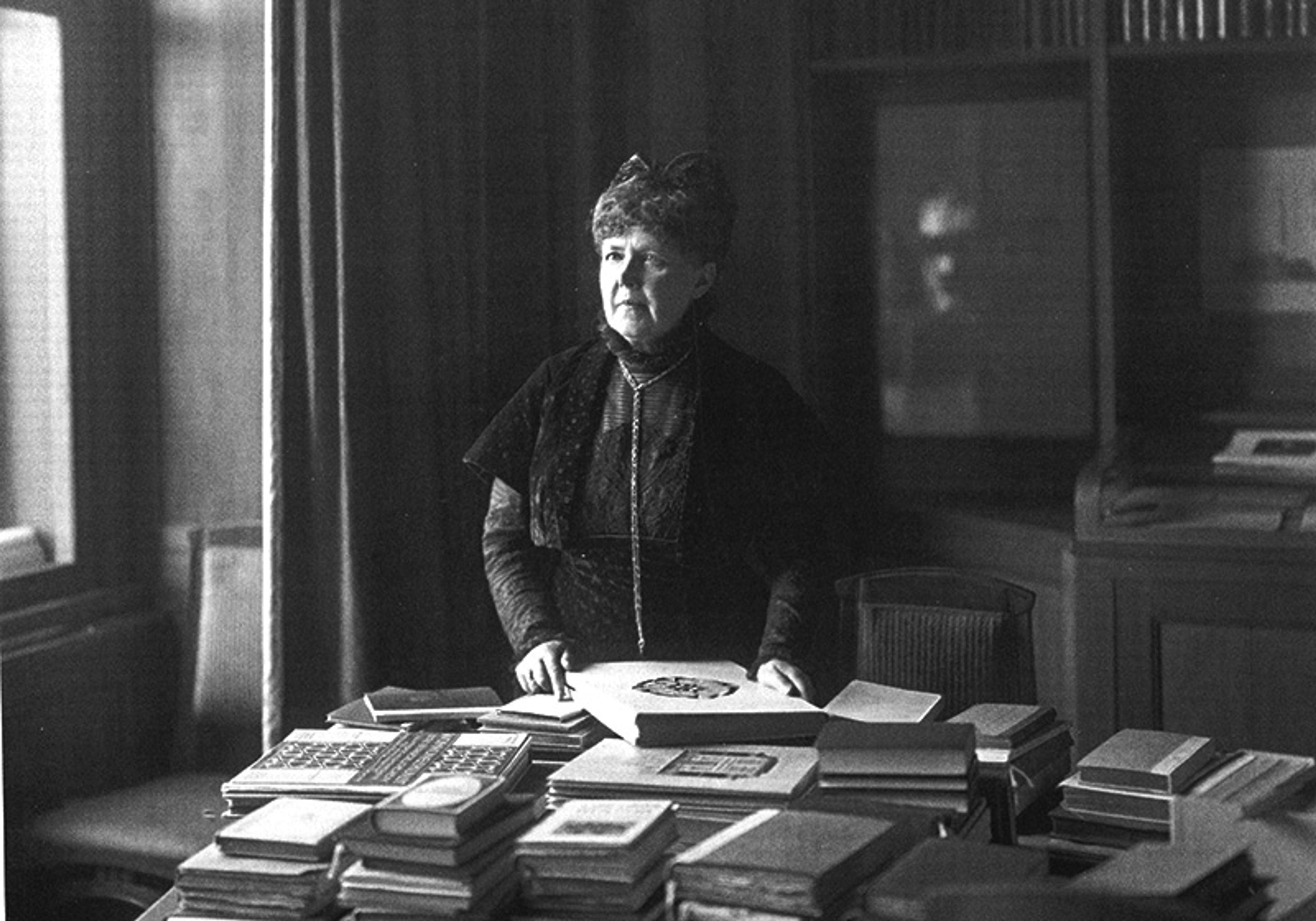

Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche in 1910. Courtesy Wikimedia

Between 1894 and 1926, she printed a 20-volume version of her brother’s works, which included her most well-known manufacturing, the e-book The Will to Energy. Taking its title from a e-book Nietzsche had at one stage deliberate to jot down, it was marketed as his magnum opus – the ultimate work he would have printed if not for his ‘insanity’.

It’s a work of true audacity – if not Friedrich’s audacity, then actually his sister’s. By selective enhancing, she was in a position to make her brother’s work not merely palatable to far-Proper readers, however a piece of advocacy for them. Nietzsche was not one to spare any specific faith from his assaults, however in Elisabeth’s palms his invectives towards different religions had been edited out, and people towards the Jews pulled to the entrance. Nietzsche’s concept of the Overman – the long run human who would have thrown off modern morality – hinted on the determine of the Führer and his minions, that’s, Hitler and the pure Aryan race he hoped to engender.

Some have argued that Elisabeth hoped to guard her brother by making his pondering extra palatable to a predominantly white, Christian readership than it could in any other case have been. Or that her enhancing was for extra private causes – she merely wished to indicate how shut they had been. One can’t, in fact, know what was occurring in her head. However the impact was that Nietzsche grew to become a type of ‘home thinker’ for the Nazis (a state of affairs not helped by the shared jagged N and Z of their names). Elisabeth herself joined the Nazis in 1930, and Hitler helped fund the work of the Nietzsche Archive. He even attended Elisabeth’s funeral in 1935.

The stain of his alleged Nazism was to stick with Nietzsche for a few years after the tip of the Second World Warfare. In his fascinating work How Nietzsche Got here in From the Chilly: A Story of Redemption (2022; English translation 2024), the German cultural historian Philipp Felsch notes that, for a lot of philosophers, notably these of the Left, Nietzsche’s work was thought to be utterly off limits – in any case, hadn’t Hitler given Mussolini a Full Works of Nietzsche as a sixtieth birthday current? One might solely hope, because the thinker Jürgen Habermas put it, that his concepts had been now not ‘contagious’ – they had been a illness the world had been cured of with the defeat of the Nazis.

Nietzsche’s archive itself was safely tucked away in East Germany, the place his works had been banned. On the time, nobody within the West knew for positive the place the archive was – solely later was it established that it had spent the years between the conflict and 1961 being carted round in wood crates to be guarded at numerous Soviet army posts, earlier than being dumped again outdoors Villa Silberblick, the place Elisabeth had tended her brother for the previous few years of his life.

They had been following the dream of each archivist – to seek out the actual author behind what they’d printed

The duty of transcribing and curating the archive fell – to everybody’s astonishment – to 2 Left-wing Italian students, the younger philosophy scholar Mazzino Montinari, who did his work at Villa Silberblick, and his trainer and mentor Giorgio Colli, who collated the fabric recovered by Montinari.

The amount of fabric was overwhelming – the variety of wood crates was greater than 100, containing, as Felsch notes:

an nearly unfathomable abundance of fabric: truthful copies and first printings of books printed by Nietzsche himself; the lecture manuscripts and philological treatises from his time as a professor in Basel; the portfolios stuffed with unfastened pages with concepts, ideas, and excerpts; in addition to the notebooks he had used to report his streams of thought.

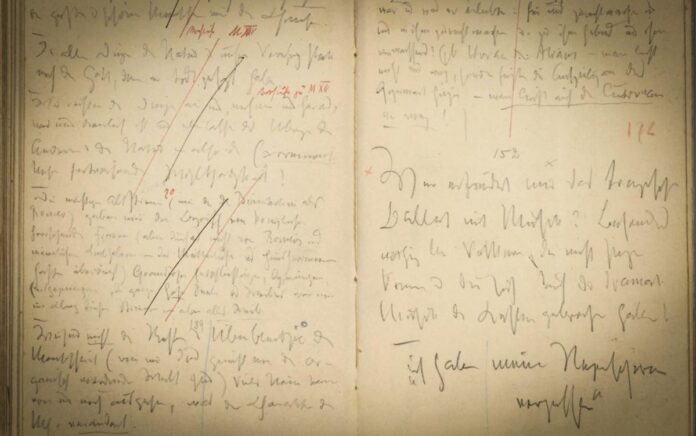

The unpublished fragments – a type of mental diary, albeit a chaotic one – totalled upwards of 5,000 pages. To Montinari fell the duty of transcribing Nietzsche’s dreadful, hurried handwriting, generally taking an entire day to complete one web page. Conscious of Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche’s distortions, the curators wished to get again to what Nietzsche had really written.

However what had been they on the lookout for? In Montinari’s phrases, they had been on the lookout for ‘the true Nietzsche’ – which is greater than only a more true model than the one his sister introduced. They had been following the dream of each archivist, and of many an off-the-cuff reader – to seek out the actual author or thinker behind what they’d printed. It’s a seek for an urtext, an unique from which the concepts develop. This is the reason Proust had his notebooks burnt – the model of occasions and ideas he become literature was, as soon as finalised, the ‘true’ model.

Whereas distancing themselves from Elisabeth’s work, Montinari and Colli’s personal was nonetheless a process of inclusion and exclusion – which fragments belonged to the archive, and which didn’t? Take for example one fragment that reads, in citation marks: ‘I’ve forgotten my umbrella.’ Is that this a part of Nietzsche’s archive? If not, why not? And whether it is, then couldn’t something be – from laundry lists to a journal of when it’s time for the bin to exit.

Montinari and Colli felt that there have been sound philosophical causes for together with and excluding fragments, or no less than that their choices might be defended. It was an concept that might be challenged from two sudden quarters.

If Nietzsche was reviled in many of the West, then his inventory was presumably lowest in France – the nation had, in any case, been occupied by the Nazis, and lots of of its intellectuals after the conflict took highly effective Left-wing positions in a rustic the place a 3rd of the inhabitants had voted Communist in 1946.

However in 1964, at a convention on Nietzsche in Royaumont, a Cistercian abbey north of Paris, new French intellectuals, within the type of Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault, got here out towards the thought of a ‘true Nietzsche’ – or a real anybody, for that matter. It was exactly the strangeness and the inconsistency of Nietzsche that made him the thinker he was. Any act of exclusion was an act of violence – what gave anybody the proper to ‘determine’ on what Nietzsche ‘actually meant’, and to exclude no matter was deemed superfluous to, or incompatible with, that that means?

The assault was taken up by Derrida, who in a 1972 paper on Nietzsche mocked the type of painful scholarly critiquing of precisely one fragment of the archive: the journal entry that claims: ‘I’ve forgotten my umbrella.’ What attainable standards might there be for its inclusion? Or for its exclusion? Definitely, the that means was clear, writes Derrida:

Everybody is aware of what ‘I’ve forgotten my umbrella’ means. I’ve … an umbrella. It’s mine. However I forgot it.

However its place in Nietzsche’s writing might by no means be pinned down exactly – might or not it’s a code? A dream? Did the citation marks round it imply he was merely pretending he had forgotten his umbrella? Might or not it’s the final line of a joke he was making an attempt to recollect? Or may or not it’s a reminiscence peg for the best perception within the historical past of philosophy? Anybody who presumed to know was uttering a falsehood – and that was true of each line Nietzsche left unpublished.

The reader would curate, embody and exclude as they noticed match. They may escape the dominance of the editor

For thinkers like Derrida, alive to energy relationships, the imposition of that means all the time ran the danger of ‘totalitarianism’ – this model of the reality and no different. It doesn’t matter how nonpartisan a researcher or editor is perhaps, nonetheless they introduced their very own preconceptions, agendas and blind spots to their work.

The second assault on the methodology of the Italians got here in 1975. The primary quantity of a brand new archive of the work of the German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin was to be printed, and the archive would include – all the things! Whereas the job of transcription would nonetheless be executed, that of curating wouldn’t, besides to place the fabric in chronological order. The reader would then curate, embody and exclude as they themselves noticed match. They may escape the dominance of the editor.

This was a precursor to an much more open type of archiving – the facsimile version. Know-how now allowed the photographing of manuscript pages, in order that they might be considered as books or, later, on CD-ROM after which on-line. The ultimate late Nietzsche volumes of Montinari’s version had been to be printed lengthy after his dying, with the writer saying they’d consist in ‘the transcription of Nietzsche’s full notations, within the spatial association of the manuscripts with all slips of the pen, deletions, and corrections – and now not within the rectified type of linear texts.’

Nietzsche had began out as a philologist – a self-discipline that explored literary texts via shut studying as a way to discover their ‘genuine’ or ‘true’ that means. Later, he would dismiss the sector as a ‘science for cranks’, ‘repetitive drudgery.’ However he additionally stated this:

Philology needs to be understood right here, in a really common sense, because the artwork of studying nicely – recognising information with out falsifying them via interpretation, with out dropping warning, endurance, finesse within the drive for comprehension… whether or not regarding books, newspaper columns, destinies or climate occasions.

Climate occasions resembling may require an umbrella? In a footnote, Felsch notes that the supply has now been discovered – it’s taken from an illustrated e-book of 1844 referred to as Un Autre Monde (One other World), illustrated by Jean-Jacques Grandville, with textual content by Taxile Delord. It’s a e-book of visible illusions, imaginary worlds, absurd taxonomies, and a satire on society and on books. What did it imply to Nietzsche? In opposition to Derrida’s competition that nothing will be pinned to this fragment, students now delve into Un Autre Monde, dissecting it for Nietzschean resonances.

Nietzsche’s final printed e-book was Ecce Homo, which interprets as ‘Behold the Man’, with the subtitle ‘How One Turns into What One Is’. It acts as a type of memoir, and the chapter titles – ‘Why I Am So Smart’, ‘Why I Am So Intelligent’, ‘Why I Write Such Good Books’ and ‘Why I Am Future’ – will be learn as both honest or as comedy – he was nicely conscious nobody was shopping for his books, not to mention studying them. Misplaced in insanity, he had no say in how he can be remade, however did provide a remaining plea in Ecce Homo that any public determine may provide: ‘Hear me! For I’m such and such an individual. Above all, don’t mistake me for another person.’