Some years in the past, I sat in a BBC boardroom dealing with a panel of senior editors interviewing me for a promotion. After treading water in a junior function for years, I needed the job greater than something. One of many editors requested me a query about teamwork however, as I reached for my anecdote and began to talk, one thing unusual started to occur inside my head. A track began to play on repeat. The wheels on the bus go spherical and spherical, spherical and spherical, spherical and spherical. I’d sung the track to my kids as toddlers. However now its cheery tones have been an exacting demand. I chanted it in my head – spherical and spherical, spherical and spherical – feeling compelled to grind my enamel collectively in time. I additionally wanted to blink.

I wasn’t absolutely conscious of doing this additional hidden work as I recounted my story of the late visitor and the impatient presenter: simply vaguely acutely aware that telling it felt actually arduous, like making an attempt to have an in-depth dialog in a nightclub. In the meantime, the tyrannical one-man band in my head stored on going. I used to be decided the panel ought to see none of it. However then I discovered myself blinking madly and caught the pinnacle of division eyeing me. I used to be rumbled.

Through the years, my obsessive-compulsive dysfunction (OCD) has manifested in a panoply of painful and punitive habits. Scraping my tongue over my enamel, performing advanced eye actions, peeling the pores and skin off my lips till they bleed. It’s worse when the stakes are excessive: when I’m making an attempt to do one thing prestigious, or with somebody I need to please. It’s additionally unhealthy once I’m making an attempt merely to exist within the second. Additionally, once I’m making an attempt to let go and have enjoyable. My OCD is insidious and form shifting, evading acutely aware consciousness or management. It appears to have a will of its personal. Besides that, in fact, it’s a half of me.

OCD is barely one of many methods wherein I work in opposition to myself. I’m a procrastinator. When writing, I always break my focus by scrolling, and I expertise an urge to examine e mail once I need to spend high quality time with my kids. I’m additionally an addict. Not a pathological addict, however a normalised on a regular basis addict. I’m hooked on screens (although I don’t personal a smartphone) and use alcohol to modify off within the evenings (although I drink lower than the advisable weekly allowance). I’m hooked on producing and attaining, too; to ticking issues off to-do lists, to busyness, to filling each second – whilst I crave time and house to mirror.

Procrastination, distraction, habit and OCD are all types of self-sabotage. It’s a curious reality of life that we hurt ourselves, even when occasions are arduous; even after we want all the assistance we can get.

Self-sabotage takes many kinds. When you’re something like me, you’ll mess issues up if you’re placed on the spot, blanking when requested a query in public or blurting idiotic strains if you’re out to impress. When you’ve made house in your day to do one thing you actually need, you too may end up frittering away these treasured hours on life admin and social media. Maybe you’ve criticised a long-suffering companion about silly, trivial issues, to the purpose you are worried they might truly pack up and go away. Otherwise you criticise your self endlessly, so it truly stops you making progress. Self-sabotage is about deferring our acknowledged targets and – after we are given a shot – blowing it, or subtly hindering our probabilities. The puzzle is why so many people perpetually discover ourselves getting in our personal manner and disrupting our best-laid plans.

In the Phaedrus, Plato makes use of the metaphor of a chariot to explain how the human psyche is split in two. The charioteer is guiding two winged horses, one mild and one darkish. The sunshine horse symbolises our excessive ethical intentions. The darkish horse refuses to obey the whip. The sunshine horse pulls the chariot upwards in the direction of fact, magnificence and knowledge. The darkish horse is irrational and undermining, pulling the chariot all the way down to earth.

This mannequin of a cut up self has echoed by way of historical past, within the work of thinkers as numerous as Friedrich Nietzsche and the psychiatrist R D Laing. Lately, neuroscience has come to dominate the sector of human psychology; and it has some helpful issues to say about why we subvert our personal ‘higher self’. Tobias Hauser, professor of computational psychiatry at College Faculty London, leads a challenge to investigate what’s going on within the brains of individuals with OCD, figuring out, for instance, imbalances in these neurotransmitters that forestall the mind from regulating intrusive ideas.

Sample-forming behaviours are additionally in play. After I spoke on-line with Piers Metal, a number one professional within the science of motivation on the College of Calgary in Canada, he took me on a dizzying screen-share tour of software program he’s designed to collate the present analysis on procrastination (together with fMRI studies that observe the method within the mind) with the intention to determine underlying patterns. This meta-analysis reveals that the largest drivers are impulsive pleasure-seeking behaviours, and the delay of procrastination itself, which renders finishing one thing offputtingly distant. ‘What makes procrastination notably attention-grabbing is that it’s an irrational delay,’ Metal stated (though, as I’ll counsel later, there could also be a silver lining to types of obvious self-sabotage comparable to procrastination). ‘We do it regardless of realizing we’ll be worse off. We all know we need to do one thing, however after we look inside ourselves for the motivation, it evaporates. And we marvel what’s unsuitable with me; why can’t I do that?’

Most of us are hooked on prompt gratification, even when we aren’t ‘classifiable’ as addicts

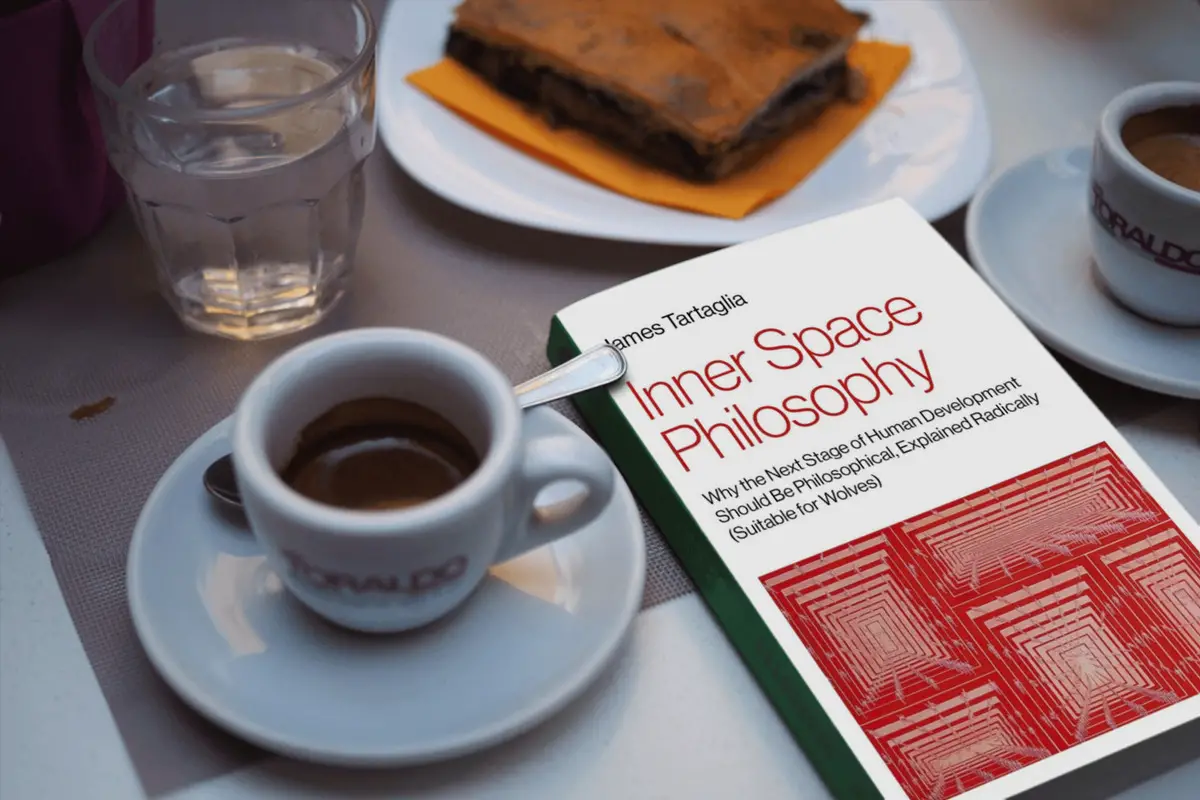

Habit arguably occupies the sharp finish of procrastination. It’s a perplexing phenomenon that’s been explored by the thinker of thoughts Gabriel Segal, who favours an method grounded in cognitive science, albeit with nods to Stoicism and Zen Buddhism. ‘There’s a very good neurological principle of habit now,’ Segal instructed me: ‘it’s called incentive sensitisation of the dopamine system.’ Usually, a rewarding expertise produces a dopamine spike that leads us to want one other reward; in addicts, this want turns into a craving. ‘That’s the elemental manner wherein habit pertains to self-sabotage,’ Segal stated. ‘You’re aspiring to do one thing, however you then really feel you could do that different factor first. It’s like changing into very hungry. You drop every thing else and get meals. And if that turns into a dominant function of your life, you simply find yourself sabotaging every thing.’

The psychiatrist Anna Lembke believes that the majority of us are hooked on prompt gratification, even when we aren’t ‘classifiable’ as addicts. Lembke, professor of psychiatry at Stanford College in California, a specialist in habit and the author of Dopamine Nation (2021), instructed me that at any time when we do one thing pleasurable we get successful of dopamine, adopted by the mind’s counter-response, which is to reset dopamine ranges again to the baseline; however with the intention to do this, the mind overshoots in a downward route, placing us in a ‘dopamine deficit state’. That’s the hazard zone, ‘the state of actual urgency or craving’, Lembke instructed me, and ‘we’ll do lots of work – broadly outlined as how a lot the organism is keen to sacrifice to get to a sure aim – to deliver ourselves again to that homeostatic baseline.’

‘Addicts typically behave in methods which can be fairly harmful to their very own functions: well being, wellbeing, jobs and relationships,’ stated Segal, just like the alcoholic who has a job interview, however will get drunk and doesn’t flip up. ‘People typically – and addicts particularly – have completely different sub-characters inside them,’ Segal continued. ‘So there might be a component of sabotaging the mature one that needs a job, however serving the aim of the interior teenager who needs to exit and have enjoyable.’

The anxiousness of accomplishment felt by many self-saboteurs is very acute for addicts. One other interpretation of the job interview debacle is that the addict fears success. ‘When you succeed, you then come beneath menace – different individuals need to throw rocks at you; knock you off your pedestal,’ Segal stated. ‘Chances are you’ll remember that, for those who succeed, any person else fails in consequence, and also you don’t need different individuals to be upset. If success brings energy, you could be afraid of what you’ll do with the ability.’

Self-sabotage – notably its widespread manifestations in habit, consuming problems and self-harm – raises advanced questions in regards to the extent to which we’re accountable for ourselves and our lives. ‘Habit is a spectrum dysfunction, from delicate to average to extreme,’ Lembke instructed me. ‘Alongside that continuum, there’s a gradual enhance in lack of company and self-determination.’ Classifying self-sabotage as a illness past the arduous border of ‘the traditional’ means we keep away from excited about these gray areas of selection and management: territory that psychoanalysis has historically been glad to inhabit.

For Anouchka Grose, a psychoanalyst and writer who has introduced her specialism to bear on such subjects as fashion, vegetarianism and eco-anxiety, this tolerance of ambiguity is exactly what makes Sigmund Freud’s work ‘radical’: ‘There isn’t a boundary between the traditional and the pathological,’ says Grose, ‘and I feel that’s a great way of excited about it. We actually don’t know the way these items are going to play out in our lives.’ I ask her in regards to the articulation of Freud’s intention, turning neurotic distress into regular unhappiness, and Grose reads it sarcastically: ‘I suppose, in a manner, the explanation that’s a sort of joke is as a result of the slippage between one state and the opposite is so discreet: it’s not such as you would ever know.’

I consider that the mechanical explanations of self-sabotage – neural pathways and dopamine responses – get us solely up to now. They’re bodily descriptions of psychological patterns and processes that may be defined in additional profound phrases: particularly, the phrases of psychoanalysis. The place neuroscience appears to demand that we overcome ourselves, psychoanalysis suggests we develop a extra accommodating and nuanced understanding of our cut up selves and contradictions. To take it all the way down to fundamentals, we interact in self-sabotaging behaviours as a result of at some degree it looks like they’re serving to. My OCD is a sort of coping mechanism. Slumping in entrance of a display or ingesting wine on a dry day is a respite from self-flagellating productiveness. Snow days, prepare strikes and pandemic lockdowns permit us to let ourselves off the hook with impunity, whilst we really feel thwarted.

Freud thought that we’re ruled by two opposing instincts. There’s the pleasure precept, related to life and creativity, and the demise drive, which is the impulse to return to an inert state. ‘We’re all after a sort of homeostasis,’ says Grose, ‘and pleasure needs to be managed very fastidiously … not doing issues is definitely fairly snug, besides that it tricks to the purpose the place not doing issues turns into morbid and deathly.’ A wholesome steadiness, in different phrases, have to be maintained between the 2 impulses: as Grose put it with down-to-earth wit: ‘You must stay, it’s important to act … and also you additionally need to flop.’

Self-sabotage turns into problematic solely when the demise drive is just too dominant. Concern of failure, for instance, can overpower our ambitions. So we put obstacles in our personal path with the intention to hold the painful actuality of our imperfection at bay – not making ready nicely for these job interviews or public appearances, or behaving erratically. What the psychoanalyst Ronald Fairbairn in 1952 referred to as our ‘inside saboteur’ tries to guard us from disgrace. Nevertheless it does so at a excessive price, foreclosing the potential of novel, artistic and genuine experiences, even perhaps hope. Grose believes that the recommendation to ‘get out of your consolation zone’ is known as a reminder to withstand the demise drive and interact with life: ‘don’t procrastinate, truly do that factor, regardless that it’s terrible. Write your ebook, regardless that you may fail.’ Though we expect we need to do nicely, this comes with the danger of inciting envy in others which may rebound upon us, changing into ‘a profound supply of comeuppance’, the psychoanalyst Josh Cohen instructed me throughout a dialog filled with humorous exasperation at these inhibitions: ‘The subtext is, What am I doing having fun with myself at this second? Who do you assume you might be!?’

The interruption is a type of self-sabotage, nevertheless it additionally expresses a necessity for connection and validation

If we’ve all-powerful tendencies that overinflate our sense of our personal harmful capabilities, we might scupper our probabilities of happiness or fulfilment to defuse the potential of harming these round us. Even when we simply have ideas and emotions in the direction of family members that make us really feel unhealthy (together with what the household therapist Terrence Actual calls ‘regular marital hatred’), we will flip that aggression on ourselves, which stops us having to correctly personal these impulses. Freud referred to as this inside decide and jury the superego, and what ought to be a essential system of checks and balances can change into tyrannical.

Carl Jung got here up with one other helpful idea so as to add to our saboteur’s toolkit: the shadow self. The shadow self is the elements of ourselves that we label undesirable, or that we expect society will reject: unmet wants, say, or aggressive impulses. We cut up off these elements, however they revolt in opposition to us powerfully and unpredictably, as erratic outbursts, psychological blocks or bodily illnesses that compromise our plans. ‘When an interior scenario will not be made acutely aware,’ wrote Jung in Aion (1951), ‘it occurs outdoors, as destiny.’ An instance is the employee who always distracts herself with social media. The interruption is a type of self-sabotage, nevertheless it additionally expresses a necessity for connection and validation that she has repressed as invalid, and which emerges with redoubled pressure in these procrastinatory habits.

Jacques Lacan described the paradox that, whereas we concern failure, success might provoke extra anxiousness. The ‘curse of the lottery’ strikes when profitable tens of millions generates sudden discontent; or consider the person who, all his working life, appears ahead to retirement, however experiences a disaster when the construction of his day job is eliminated. I’ve felt a minor model of this once I’ve gone on a long-awaited vacation and located myself fiddling; at a unfastened finish, I snap at my household, and scroll British information headlines so I can make amends for home gloom. To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, there are solely two tragedies in life: one will not be getting what one needs, and the opposite is getting it.

If self-sabotage exists on a spectrum, the up to date world – with its alluring screens and overwork tradition – has made it much more prevalent. Types of self-sabotaging behaviour beforehand classed as irregular have change into ubiquitous. There was a 400 per cent enhance within the variety of British adults looking for a analysis for ADHD since 2020, in line with Tony Lloyd of the ADHD Basis. And, in line with Metal, about 95 per cent of individuals admit to procrastinating no less than a number of the time. A rising variety of younger individuals ask for extenuating circumstances to finish the coursework for a level they might ostensibly actually take pleasure in. Universities are coping with a whole system on the point of logical absurdity and administrative collapse. Confronted with collective self-sabotage within the type of local weather change and an ever-more aggressive jobs market, many younger individuals look like turning the anxiousness upon themselves, inducing a sort of paralysis. We should always train warning after we hyperlink psychological sickness to ambient circumstances comparable to geopolitics or the dominance of screens. Nevertheless it’s additionally value contemplating why self-sabotage is such a function of contemporary life.

The massive change is that diversions from our chosen path seem at each flip. The researchers I spoke to pointed to current analysis on the affect of screen time, notably social media. ‘We’re hacking our personal working techniques, and entrepreneurs have in a short time found how one can exploit our impulsivity,’ Metal instructed me. ‘Procrastination is on the rise as a result of there’s a trillion-dollar business to get us to take pleasure in these smaller sooner temptations at the price of our bigger later goals.’ The thinker Harry Frankfurt in 1971 defined these as first-order and second-order wishes. So, our first-order want could be to have a look at Instagram, however the second-order want could be to change into an artist. We are able to solely be stated to have free will when our first- and second-order wishes align. The stakes couldn’t be larger. As Metal says: ‘These are deep questions on what sort of society we need to stay in, and we’ve not designed it to maximise human flourishing.’

It’s a double battle: the world presents alternatives for self-sabotage and raises our perfectionist expectations

Our display addictions forestall us from carrying out our larger targets, however in addition they forestall us from resting and residing within the second – one thing we’re always instructed is sweet for us. ‘We don’t know how one can calm down anymore with out digital media,’ stated Lembke. ‘The best way that we now calm down is to take a break from our externally targeted consideration after which to mind-wander, facilitated by social media. However, in essence, after we’re doing that, we’re consuming a drug and so we’re probably not permitting ourselves to return to a homeostatic baseline.’ We are able to neither correctly get on with our work, nor really sit nonetheless.

We’re ‘nurtured in a aggressive, individualistic ambiance’, stated Cohen. His pursuits are wide-ranging; he’s written about anger, how one can live, being a loser, and he’s questioned whether or not we even possess a private life, whereas his book Not Working (2019) presents a critique of our workaholic tradition. Prior to now, our sense of obligation got here from the superego: a tough taskmaster, however in some way contained. However, beneath capitalism, the compulsion comes from one other Freudian idea, the ‘ego supreme’, which is extra inside and insidious. ‘The ego supreme by no means says “you could”, it says “you’ll be able to”,’ Cohen defined. ‘Below the gaze of our personal perfection, our personal punishing supreme, we’re all the time falling brief.’

So we appear to be combating a double battle: the up to date world presents available alternatives for self-sabotage and it raises our perfectionist expectations, making distraction and habit extra tempting. In addition to resulting in overwork, the ego supreme makes us much less good at our work, too: one other downwards spiral. This frame of mind is ‘efficiency wrecking’, says Cohen: ‘you lose conviction and confidence in your self. The extra you’re conscious of falling behind, of not fairly being on the degree you’re speculated to be, the extra it does one thing to your capability to seamlessly produce.’

Can self-sabotage be decreased or eradicated? So as to consider what may assist, we have to distinguish between the self-sabotage that’s attributable to the up to date world, and that which is just a component of us.

So far as the exterior world is anxious, Lembke takes an authentic and bracing method, arguing that we have to ‘change the narrative’ away from the drive to expertise pleasure to ‘a brand new type of asceticism’ that paradoxically will allow us to realize what we’re actually after. When Lembke considers the issue of younger individuals failing to launch themselves into the world, in a rising variety of circumstances ‘it’s not that their lives are too arduous. It’s that their lives are essentially too simple, and that with extra friction they might discover extra objective. With extra objective, they might have the ability to endure the ache of being alive. As a result of it might have no less than some which means for them.’ The best way to do that, she argues, is to create ‘a world inside a world the place we insulate ourselves’ from these ‘extremely reinforcing substances and behaviours’. Equally, Metal has discovered that one treatment for procrastination is placing pleasures a bit out of attain: ‘We’d like delays, and even small ones will be very efficient.’

Past switching off the web and taking chilly showers, a primary step in limiting our self-sabotaging tendencies is to recognise that we’ve them. In some methods, we’ve come a great distance as a tradition in appreciating that we don’t all the time act in our personal finest pursuits. Behavioural economists like Daniel Kahneman, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein have questioned the mannequin of ‘homo economicus’, the rational, self-determining particular person. They’ve documented how irrational we truly are: we neglect our pensions, stick to our overpriced insurance coverage, and demolish mediocre takeaways on the couch. The equal in political principle is fake consciousness: as Thomas Frank places it in What’s the Matter with Kansas (2004), it’s the conundrum of ‘working-class guys in midwestern cities cheering as they ship up a landslide for a candidate whose insurance policies will finish their lifestyle, will remodel their area right into a “rustbelt”, will strike individuals like them blows from which they may by no means get better.’

Making sense of the deeper logics beneath what’s dismissed as perverse will be the simplest treatment

Within the mainstream dialog about ‘wellbeing’, nevertheless, self-sabotage can seem counterintuitive. The self-optimisation motion is pushed to some extent by a recognition of the necessity to overcome unhealthy habits, however its positivity (encapsulated by the injunction to stay your finest life) can downplay our emotions of being uncontrolled and irrational, making us really feel unhealthy for being merely ‘usually sad’. Right here it resembles the rhetoric of self-management that pervades in style discussions of neuroscience: the belief that if it’s bodily, it’s fixable. Psychoanalysis, in contrast, understands very nicely how and why we undercut our acutely aware intentions. Reasonably than eliminating these elements of the self, psychoanalysis brings them into the sunshine, the place we will higher perceive them.

In actual fact, making sense of the deeper logics beneath what’s dismissed as perverse will be the simplest treatment. OCD’s triggers could also be genetic, however they’re additionally contextual: maybe you have been made to really feel, from an early age, that your pure feelings – particularly rage, but in addition wishes that felt underserved or dangerous – have been toxic. Such conditioning pops up like a self-appointed safety guard, protecting that ‘shadow self’ toxicity channelled away inside. The bestselling in style psychiatrist Jeffrey M Schwartz, who champions our capacity to rewire our neuroplastic brains, advocates a mix of acutely aware consciousness (or mindfulness) of the compulsions, whereas excited about why they happen – an method that has actually labored for me. Although it might look much less empowering on the floor, I’m reminded right here of Melanie Klein’s perception in the necessity to change our idealised self with our precise self, so we would reconcile ourselves to the tough actuality of our imperfection. We are able to defuse our deep-seated concern of envious revenge, for instance, by seeing it as our personal projection – a technique which may have rescued my BBC interview.

Comprehension results in self-compassion. Accepting the fact of self-sabotage loosens its grip. We’d like ‘to work with our symptom fairly than “return to regular” or assume that there’s a type of benchmark human,’ Grose instructed me. The duty is ‘how one can embody your symptom in a life you can stay – and like.’

Maybe, then, we don’t need to jettison our self-sabotaging tendencies altogether. Paradoxically, famend analysts comparable to Freud and Jung deployed their very own struggles with self-sabotage to spark progressive and inventive breakthroughs – delving into their neurotic, maddening lack of ability to work to assist them perceive these tendencies in us all. Jung had hallucinations and heard disturbing voices – documented in his fantastically illustrated masterwork, The Purple Ebook – that have been each debilitating and groundbreaking. Freud’s letters reveal that, across the age of 40, he confronted the insufferable realisation that he wouldn’t have the ability to accomplish his life aim of explaining all human psychology when it comes to the bodily workings of the mind. He complained of ‘a sense of melancholy’ that took the type of ‘visions of demise … rather than the standard frenzy of exercise’. He discovered he couldn’t quit smoking and was ‘fully incapable of working’, declaring that ‘in occasions like these my reluctance to put in writing is downright pathological’. However then he had a revelation, and moved past this narrowly scientific challenge into an exploration of fantasies and goals. ‘Signs, like goals, are the fulfilment of a want,’ he wrote, realising that his neuroses have their very own needs. Solely when he attends to them is he capable of invent the self-discipline of psychoanalysis.

Self-sabotage could also be debilitating, nevertheless it may also be a spur. Fairly often, it’s the engine of productiveness – and humour. There’s something treasured in regards to the neurotic tangles that make lots of our most relatable cultural figures who they’re – I’m considering of George Costanza within the TV present Seinfeld. ‘A lot of people who find themselves very profitable are on that boundary,’ Grose instructed me. ‘It’s a tight-rope act between being insane and good.’ One of the best we will hope for, maybe, is having individuals we will depend on to avoid wasting us from ourselves. In spite of everything, it labored for Marcel Proust. ‘Proust was a complete perfectionist, and drove his writer mad,’ Grose stated. ‘Left to his personal units, who is aware of what would have occurred. However that was his course of, and fortuitously, in his case it was potential for somebody to step in and say: we’re going to press, proper now. It’s time to cease!’