At the moment’s fashionable wind generators appear to repel poetic or creative engagement. It’s troublesome to think about a panorama painter portraying their spare traces and uniform rows as icons of a pastoral idyll, because the windmills of the previous typically had been.

Perceptions of contemporary wind generators appear worlds away, for instance, from how Robert Louis Stevenson described the windmills of England in 1882:

There are, certainly, few merrier spectacles than that of many windmills bickering collectively in a recent breeze over a woody nation, their halting alacrity of motion, their nice enterprise, making bread all day, with uncouth gesticulations, their air gigantically human, as of a creature half alive, put a spirit of romance into the tamest panorama.

The points that struck Stevenson – the movement of windmills, symbols of prosperity, on the horizon – had been highlighted a decade earlier than by the French novelist Alphonse Daudet in his depiction of Provençal life:

The hills all in regards to the village had been dotted with windmills. Whichever manner you regarded, you may see sails turning within the mistral above the pines, and lengthy strings of little donkeys laden with sacks going up and down the paths; and all week lengthy it was a pleasure to listen to on these hill-tops the cracking of whips, the creaking of the canvas of the sails, and the shouts of the millers’ males … These windmills, you see, weren’t solely the wealth of our land, they had been its delight and pleasure.

But perceptions of windmills haven’t been uniformly idyllic. Since they first appeared on the panorama of medieval Europe, windmills represented an imposition of the technological on the pastoral. They had been, within the phrase of the wind vitality writer Paul Gipe, ‘machines within the backyard’, straddling the boundary of the agrarian and mechanical. In contrast to the static applied sciences shaping landscapes – from cathedral towers or canals up to now, to energy traces, photo voltaic panels or rows of genetically modified crops at the moment – windmills are continuously in movement. They refuse to passively disappear into the panorama.

With the unfold of contemporary windfarms, the cultural positioning of wind energy stays a contentious problem. However the debate isn’t new: for hundreds of years, the symbolic nature of windmills – as technological monsters or icons of the idyllic – has been open to query. Understanding this debate might help open new avenues for engagement with at the moment’s wind know-how.

Though European windmills first appeared as early because the eleventh or twelfth centuries, there are nonetheless clues to how this new know-how was initially perceived. In Dante’s Inferno, as an example, when the poet reaches the deepest circle of hell, Devil turns into seen by way of the gloom. Because the ominous determine seems, he’s described with a metaphor that might have been rising acquainted to a lot of Dante’s unique 14th-century readers:

As, when thick fog upon the panorama lies,

or when the evening darkens our hemisphere,

a turning windmill appears afar to rise …

By the darkness, the satan’s big limbs are seen just like the sails of a windmill pinwheeling on the horizon. To readers whose largest constructed realities had been steady, unmoving church towers or metropolis partitions, the ceaseless, arching sweep of a windmill’s arms was little question disconcerting to say the least. Later, when Cervantes pictured them as giants in Don Quixote’s creativeness, he might gesture to this lingering unease over this most outstanding construction on the medieval horizon.

Windmills grew to become integral to communities: buildings with names, histories and inhabitants

Apart from their visible impression, the primary windmills additionally challenged present vitality infrastructure. Since Roman instances, energy to mill grain had been confined to water mills and remained the property and guarded prerogative of feudal landowners. As the primary windmills unfold all through England, they had been greeted with resistance by landowners trying to protect their historical rights. Windmills ‘threatened each profitable previous water mill franchises and conventional upper-class privileges,’ recounts the historian Edward Kealey in Harvesting the Air (1987), and ‘supplied quick-witted peasants a possibility to evade manorial rules, act independently, and grow to be fairly affluent.’ Indignant landowners ordered unlawful windmills be torn down.

A Windmill close to Brighton (1824) by John Constable. Courtesy the V&A Museum, London

But ultimately this disrupting, disquieting know-how grew to become a side of the pastoral splendid. Windmills grew to become integral to communities: buildings with names, histories and inhabitants. Working a windmill took talent, care and a spotlight. The miller, who lived within the windmill, was totally occupied with watching the climate, trimming the sails, and preserving the windmill useful from technology to technology – in addition to offering a significant agricultural function locally by grinding grain. In the end, because the artwork historian Alison McNeil Kettering has argued, windmills took on the function of ‘cultural signifier’, representing provision and guardianship over a well-run group, changing into acquainted icons of ‘pastoral tranquility’ and ‘agrarian idyll’.

Because the final technology of millers cared for the final windmills delivering England, their aesthetic worth lingered at the same time as their industrial worth disappeared. As Stanley Freese wrote in Windmills and Millwrighting (1957):

[N]both {photograph} nor drawing can seize for my pages probably the most lovely of all nation scenes; solely those that have caught sight of the large white sails of a windmill following each other towards a background of darkish hills or woodlands, or black canvas sails hovering one after one other into a night sky, can totally apprehend the attribute great thing about this construction, which differs from all others as a result of it’s alive with comely movement, by no means awkward or ungainly, however mixing effectively with each type of panorama.

As steam changed wind in Europe, a brand new kind of windmill emerged throughout the Atlantic. Whereas European windmills had been inhabited buildings positioned inside the group, the unsettled expanse of the western United States noticed the windmill altered to run for many years in isolation, pumping water for farmsteads or for cattle stations scattered throughout a whole bunch of miles of arid ranchland. Dozens of fashions represented a Darwinian response to this environmental problem: self-lubricating mechanisms, designed to trace and spill the wind with counterweights and is derived, their complicated down-gearing remodeling rotary movement into a gradual back-and-forth pumping motion in even the lightest breeze. By 1889, there have been greater than 70 windmill factories in cities throughout the American Midwest. On the European windmill’s peak, there have been maybe 100,000 of the buildings throughout Europe; in contrast, there would ultimately be greater than 6 million windmills in the US.

Lame Deer, Montana, September 1941. Picture by Marion Submit Wolcott, Library of Congress

In contrast to the swish European windmill, the brand new US selection was thought-about ugly and ungainly. An American architect insisted that American windmills ‘needs to be condemned’ as offensive to sight: ‘To see these awkward, spider-like buildings dancing fandangos earlier than our eyes disturbs the repose and mars the panorama of our in any other case lovely properties.’ Worse, one other writer mentioned the countryside was affected by wrecked windmills, casualties of the failure to take care of or lubricate – this final chore a near-weekly requirement for a number of the earliest fashions. But regardless of these preliminary impressions, the brand new American windmill (technically, a wind pump) quickly grew to become an icon of the Western settlers themselves: impartial, self-reliant, steadily going through no matter storms arose.

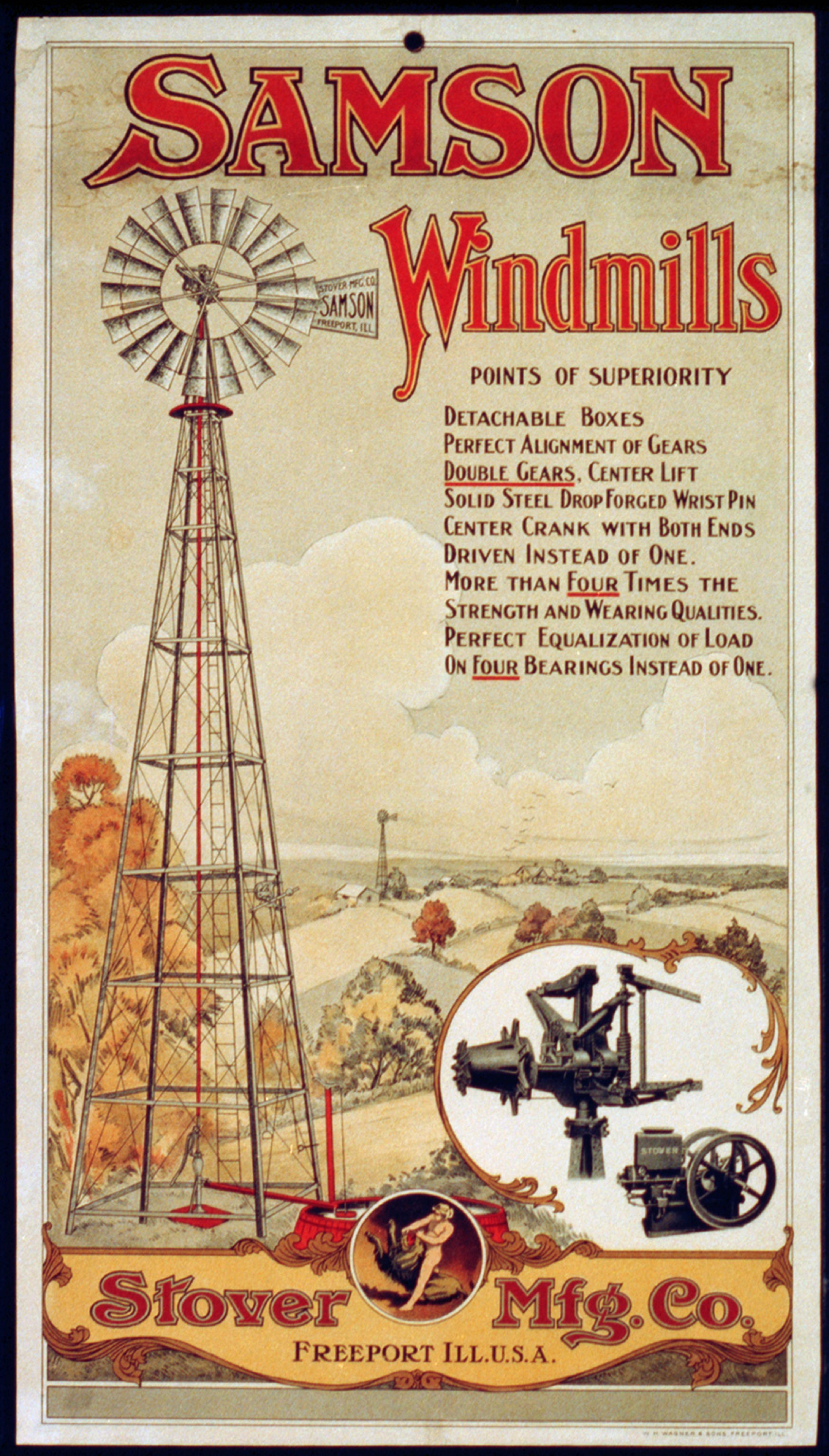

Producers helped domesticate this view of windmills as totems of the American west

A Kansas Metropolis Star reporter writing in 1964 captured the sensation of rising up within the shadow of a farmhouse windmill, an expertise widespread to generations of settlers and their descendants. There was:

the mild sough of the breeze by way of the fan, the creak of the tower and the rhythmic metallic working of the gears and sucker rod, and eventually the regular comfortable pouring of water into the tank … After which there was a sound all its personal: a blade bent by some lengthy forgotten encounter with the picket tower at every revolution – thump, thump, thump, when the wind was comfortable and at a machine-gun rattle when a summer season storm despatched up mud and useless tumble weeds racing throughout the flat … On quiet nights, for a kid awakening within the darkness of a stuffy room, the chipping of the wounded blade towards the tower took on a comforting sound, reassuring that this was residence, that there was no storm, and that the windmill was pumping water.

Just like the European windmill earlier than it, the American windmill was changing into a cultural signifier of a brand new pastoral splendid.

Courtesy the Library of Congress

Within the new industrial context, windmill producers helped domesticate this view of windmills as totems of the American west, presenting them in ads and catalogues as a part of an idyllic farm panorama. Competitors amongst producers additionally meant windmill designs grew to become as easy and reliant as potential. Windmills wanted to be shipped throughout the nation, assembled a whole bunch of miles away on the open prairie, and to function in isolation for years on finish. Their patrons wanted to personal, perceive, and repair the windmills themselves. The success of this strategy is evidenced by the windmills nonetheless spinning throughout the US and the world, with a handful of firms at the moment producing designs that stay unchanged from the 1910s. Just like the European windmill, American windmills grew to become pastoral icons, their ceaseless labour – working within the slightest breeze and weathering the harshest storm – a visible metaphor for diligence, independence and affected person endeavour.

Today’s huge wind generators are bigger than previous windmills by an order of magnitude. The query going through this newest technology of wind know-how is greater than whether or not they are going to be seen as icons of vitality independence and sustainability, or just one other extractive trade ‘replicating the exploitative practices of the infrastructures they might substitute,’ because the historian of science Nathan Kapoor put it. Moderately, the query is whether or not the social imaginaries out there to earlier generations of windmills – the prospect to grow to be symbols of provision, group or self-reliance – can be found to fashionable windfarms. It’s a query taking part in out, as an example, in debates between farmers who welcome wind generators and the earnings they characterize and people – typically inside the generators’ shadow – who see them as monstrous technological impositions on the panorama.

What prevents fashionable wind generators from the form of cultural integration that European and American windmills obtained? A part of the reply comes by contemplating wind applied sciences in gentle of labor by the thinker of know-how Albert Borgmann. In his classic Expertise and the Character of Modern Life (1984), Borgmann presents his evaluation of ‘machine’ as each critique and exemplar of contemporary know-how. According to Jesse S Tatum, a tool is a technological artefact designed to make ‘a single commodity extremely out there whereas making the mechanism of its procurement recede from view’. Our present technological paradigm is the creation of as many gadgets as potential, from vehicles to electronics to infrastructure, to make commodities hyper-convenient and ample.

The issue with gadgets is that, by design, they’re black bins. Gadgets, in Borgmann’s remedy, are inaccessible to understanding or engagement. They demand no talent, disburdening their customers whereas, in Borgmann’s phrases, resisting ‘appropriation by way of care, restore, the train of talent, and bodily engagement’. Gadgets, whether or not kitchen home equipment or {the electrical} programs that offer their vitality, neither specific their creator nor ‘reveal a area and its explicit orientation inside nature and tradition.’ Writing in 1984, lengthy earlier than the arrival of smartphones, Borgmann’s evaluation is prescient in highlighting how technological gadgets present important commodities corresponding to data, leisure, vitality and meals, whereas concurrently preserving the technique of their manufacturing inaccessible and largely invisible.

Not possible to devour the commodity of floor grain from a windmill with out ‘invoking or enacting a context’

Regardless of the abundance of commodities, our interplay with gadgets leaves us distracted and dissatisfied as our engagement with the world is decreased to ‘slender factors of contact in labour and consumption’. For Borgmann, the answer isn’t a return to a pretechnological setting however relatively to recentre human practices and flourishing round what he refers to as ‘focal issues’. In distinction to a tool, a focal factor is ‘inseparable from its context, particularly, its world, and from our commerce with the factor and its world, particularly, engagement’. Focal issues characterize locality and craft; they interact physique and thoughts, and that engagement requires talent: ‘The expertise of a factor is at all times and likewise a bodily and social engagement with the factor’s world.’

Focal issues invite customers to work together with them, giving rise to what Borgmann calls ‘focal practices’ that make the factor a part of the broader tradition and social construction of the group. The European windmill, dependent in its operation on the talent and care of the miller, in its building and upkeep on the data and experience of carpenters and millwrights, and in its goal on native agricultural practices, was a quintessential Borgmannian focal factor – a nexus of fabric tradition, social heritage and creative expression. It was unimaginable to easily devour the commodity of floor grain from a windmill with out ‘invoking or enacting a context’.

Likewise, American windmills, although manufacturing unit manufactured on a big scale, instantly entered the context of homestead or ranch. They had been designed to be open and accessible to customers for care and upkeep, and the farmer or rancher took possession and exercised talent in that upkeep and care – studying the idiosyncrasies of every particular person windmill. Whereas offering the important commodity of water, windmills took on extra symbolic and cultural roles, providing a way of solace, wellbeing and aesthetic pleasure (as evidenced by their reappearance on smaller scales as garden ornaments throughout the Midwest and past). Each European and American windmills, in accordance with Borgmann’s paradigm, functioned as focal issues – technological artefacts that linked their customers and communities to each panorama and wind.

Modern wind generators are designed to suit the machine paradigm, offering the commodity of vitality or (to the landowner who rents house for his or her footprint) cash, however they fail in a significant respect. Regardless of how they’re remoted from close by communities or coastlines, their movement retains them seen on the horizon, at the same time as the opposite large-scale vitality infrastructure gadgets (electrical traces, telescope poles, cellphone towers) fade from view. Their main mechanism of reworking wind into vitality stays unimaginable to cover. As the expansion of sustainable vitality continues, extra and bigger windfarms shall be required, and their seen affect will solely enhance. The stress between wind generators as disengaging gadgets and their apparent presence on the panorama will proceed. Earlier iterations of windmills, nonetheless, weren’t finally accepted by making them invisible however relatively by altering how they had been perceived. Can one thing comparable occur for contemporary wind generators, remodeling them from gadgets to one thing that’s nearer to Borgmann’s focal issues, and opening a path to richer cultural and aesthetic engagement?

Wind generators are presently designed and carried out as gadgets. A minimum of partly for security and legal responsibility issues, they’re remoted at the same time as they continue to be in view. Wind generators are, like Borgmann described high-rise buildings, ‘although imposing … not accessible both to 1’s understanding or to 1’s engagement.’ However this disengagement is likely one of the most important causes wind generators are sometimes seen with such negativity. Because the thinker Gordon G Brittan Jr expresses it, wind generators ‘are ubiquitously and anonymously the identical, alien objects impressed on a area however in no deep manner linked to it. They don’t have anything to say to us, nothing to precise; they conceal relatively than reveal.’

Alternatively, these fashionable windmills have many traits of Borgmann’s focal issues. Focal issues, in accordance with Borgmann, ‘are concrete, tangible, and deep … They interact us within the fullness of our capacities. They usually thrive in a technological setting.’ By depth, Borgmann signifies that all of an object’s bodily options are important, one thing acutely true of precision-designed wind generators constructed so that every curve and angle generates as little resistance and as a lot effectivity as potential. Depth means complexity, and complexity may be a side of engagement. But a lot of the complicated, elegant design of wind generators that might make them participating relatively than alien stays bodily hidden and corporately protected.

An unused turbine blade propped alongside a rustic highway permits one to expertise its scale and scope

Engagement with focal issues needn’t be bodily. Apart from the handful of expert employees who design, assemble and keep the generators (and whose work itself is a degree of potential wider engagement, as proven by the fact TV present Turbine Cowboys), most individuals will be unable to bodily interact with these artefacts in any sensible manner. However training and outreach are highly effective types of engagement largely unutilised by the assorted actors concerned within the creation and upkeep of windfarms. This is smart inside the machine paradigm: we aren’t normally invited into engagement with our electrical substations. However whether it is unimaginable to disregard them, training and engagement might help us transfer towards making wind generators focal issues.

Different avenues of engagement might be so simple as urged routes navigating drivers or cyclists on public roads by way of wind farms, permitting guests to deliberately expertise them as a part of an aesthetic vista. And although nobody needs to be climbing them, there are methods to carry their physicality nearer the observer. Close to my own residence, as an example, an unused turbine blade propped lengthwise alongside a rustic highway permits one to expertise a way of the dimensions and scope of those artefacts. The expertise of locality might be built-in with training: data corresponding to how briskly the generators spin or how a lot vitality they generate from second to second needn’t be obscured or accessible solely to consultants. These physicalities might as a substitute be methods to have interaction these passing by way of. This doesn’t imply costly interpretive centres at every wind farm (although it might); it is likely to be so simple as signage alongside the roadway. Science communicators might help right here to type bridges between the artefacts and the curious public who watches them alongside the horizon.

Although a extra sophisticated concern, possession must be thought-about as effectively. A deep sense of engagement comes about from artefacts which are individually or communally owned. It was this sense of possession that allowed US windmills their cultural function and that made European windmills a significant a part of their communities. This continues at the moment, as people and native communities lovingly restore and keep these earlier windmill iterations, although they’re now not the technique of offering the commodities they as soon as did. The present mannequin of off-site possession of wind generators is a robust issue preserving at the moment’s windmills firmly inside the machine paradigm.

For Borgmann, ‘the dignity and greatness of a factor in its personal proper’ – and the stately turning generators alongside my Midwestern horizons can definitely have this dignity – is what permits focal issues and the practices constructed round them to ‘collect and illuminate the tangible world and our appropriation of it’.

Borgmann’s machine paradigm helps make sense of cultural and aesthetic issues round fashionable wind farms, and the historical past of windmills provides hints of how issues is likely to be completely different. With out efforts of engagement, wind generators stay inscrutable gadgets, straightforward to scale back to uniform, monolithic symbols of extractive capitalism. Until we attempt to combine them into native tradition as focal issues, they’ll by no means be symbols of the panorama like windmills of the previous.