IN A RECENT PIECE FOR GAWKER, “Gary Indiana Hates in Order to Love,” Paul McAdory checked out how the author makes affective intensities cooperate. “Indiana’s greatness,” McAdory wrote, “rests partly on his skill to fling apart the sheer curtains partitioning love from hate and extract a superior pleasure from their combination.” It could be dangerous kind to cite a parallel assessment of the e book I’m taking a look at—Fireplace Season, a set of essays stretching again to 1991—or possibly it’s simply complicated to take action with out going into assault mode. Sorry, odiophiliacs! I need to merely agree with McAdory’s essay and say that consensus is fascinating. We want the actual epoxy of hate and love that binds Indiana’s finest work. He’s very a lot not a twitterhammer who chases dunks for house bucks. Indiana’s hatreds are wholesome and intertwined and varied, few of them shallow. In 2014, Indiana described William Burroughs’s tales as “torrents of Swiftian misanthropy in vignettes of atomic doom,” which describes his personal work, roughly. What it pins down, with much less roughness, is the sense of stakes in Indiana’s rainbow of rejection. Was there ever a vote on what snark really is? No matter it’s, that’s not what Indiana sells. Lots of his most barbed darts are delivered with affection, and appreciable consideration to element. In his folding rifle of a campaign-trail report from 1992, “Northern Publicity,” he describes Invoice Clinton’s face as “a visage of pure incipience: soon-to-be-jowly and exophthalmic, a fraction previous actually attractive, however warmingly cocky, clear-eyed, with an honorary, twinkling pinch of humility.” There may be a lot to like there, however it’s the “honorary” for me—the concept that Clinton has bestowed the humility on himself, thereby voiding its authenticity. However Indiana grants him “warmingly cocky,” very totally different from heat or cocky or cockily heat. No—the needle strikes slowly over the flesh till it hits a vein.

In an April Zoom interview with Christian Lorentzen, Indiana stated he most popular European novelists whereas rising up due to his sense of “foreignness” in relation to the varied American narratives being offered at house (initially New Hampshire). He added that his life as a critic started partly as a result of somebody wanted him to do the job—at first, the Village Voice. His want to write down was not tied particularly to any specific mode, past paying the hire. It’s the sense of being engaged in a wider ethical process that feels extra European than his disdain—or his style for arm-sweeping an improbability off the desk. Like so: “I’ve by no means found a single worthwhile merchandise within the remark threads hooked up to on-line tales,” Indiana wrote in a 2018 preface to Vile Days, his assortment of Village Voice artwork columns. These pronouncements are extra cautious than they first seem. Solely a author spoiling for, effectively, a comments-section combat would think about that Indiana had learn all the present remark threads and held him to that pseudoscientific baseline.

He shares the quasi-European stance with one other quasi-European, Susan Sontag, an erstwhile good friend he has typically been in comparison with. It’s not a nasty pairing to bear in mind, in that neither have any respect for punditry or specialization, two distinctly American methods of current as a author. Critic work comes simpler than fiction or drama as a result of there’s at all times a proximate want, and the necessities are nonexistent. An editor has to plug a gap, and Indiana was in a position to fill ’em all whereas he was creating performs and novels and video works and radiating out into the world from a house base on East eleventh Road, a reality he’s immune to overemphasize, given his “sturdy distaste for the Eighties nostalgia” that tends to hunt out East Villagers and amplify each their actions and their significance.

The ’80s artwork essays from the Voice are (partly) in Vile Days, and Fireplace Season solely addresses visible artwork intermittently. Indiana has a tetchy relationship to these artwork items, which he describes in his 2015 memoir I Can Give You Something however Love as “a bunch of yellowing newspaper columns I by no means republished and haven’t cared about for a second since writing them 1 / 4 century in the past.” The number of items in Fireplace Season higher fits Indiana’s remit. We start with a 2014 piece on fierce Putin critic Anna Politkovskaya, which additionally highlights among the limits to the Indiana method. When you don’t know what the Nord-Ost hostage disaster was or how Politkovskaya died, Indiana doesn’t spell it out for you. His admiration for this author’s bravery is just one impetus for the piece; when he writes “we anticipate journalists to be magically proof against actual hazard, partly as a result of they’re, technically, ‘civilians,’” he’s organising his bigger level: “It’s, in actuality, all the identical battle, all over the place and infinite, subsiding in a single place because it flares in one other.” When he quotes Politkovskaya talking about her personal work, to shut the piece, it appears clear his personal reply is not any: “The essential query is, what change has our article introduced? Has one thing modified for the higher in our society?” That conclusion is barely extra apparent eight years later. The longest piece, “LA Performs Itself,” paperwork the 1993 Rodney King trial—the second, federal continuing—with an icy thoroughness, underplaying the various blossoms of horror afforded by the cops and their vortical excuses.

Indiana cares about sentences and he cares about his buddies. “A Coney Island of the Viscera” paperwork his friendship with Louise Bourgeois and her stash of psychoanalytic writings. “Right this moment’s MacArthur genius is tomorrow’s Edna Ferber,” Indiana notes, in protection of the Bourgeois fragments not being “supposed as literary works.” The totally different rhythms and tonalities Indiana makes use of on this one brief piece do such a very good job of mirroring the thoughts’s perspective towards itself, and the way it levels data. He opens with, “Once I met her, within the mid-Nineteen Eighties, it was by means of a mash observe she despatched within the mail to the paper I wrote for, not a lot thanking me for a assessment however providing one thing higher than thanks: a terse, oddly touching missive indicating that I’d fathomed her present present very effectively.” Self-congratulatory, for positive, whereas additionally revealing the quickness of their intimacy. Maybe sensing his personal peacockery, he immediately wets the feathers: “We have been each intellectually combative, anxiety-ridden, insecure, depressive, and wretchedly insomniac, and we each sported egos liable to inflate like dirigibles, then shrink to pea-size throughout the span of a sneeze.” As for her hoarding, he retains it fast: “She by no means threw something out.” Right here, and elsewhere, Indiana is a staunch defender of the formally uncommon, the writing that resists simple flogging. He takes Bourgeois’s writings as significantly as he takes her artwork, calling them “shut mimicries of consciousness” which “essentially resist cohesion.” He reads her cussed little poems with a grave affection. “Some pages merely checklist associations round an remoted fixé,” Indiana writes, “like a broth discount.”

“Northern Publicity,” initially for the Voice, is an effective instance of his care and carefulness mixed. (Together with the King piece, this report makes a robust case for Indiana being employed proper now, at the moment, as a characteristic author unburdened by a phrase depend ceiling.) Watching Jerry Brown communicate, he’s aggravated, presumably due to “the reminiscence of a giant crow I as soon as noticed bisected by one in all Jerry’s power-generating windmills outdoors San Luis Obispo.” But it surely’s not that—it’s the small baby enjoying with a Nintendo Sport Boy subsequent to him. These technological particulars time-stamp this piece superbly, however it’s that must each report and observe that characterizes Indiana’s finest work. (He advised Lorentzen he moved away from criticism initially as a result of he needed to do extra reported work.) First referencing the “tedium of the marketing campaign path,” Indiana writes that he was “moved to tears one morning by a CNN report on unemployed manufacturing unit employees in West Virginia.” OK—not a monster, not an elite perched within the opinionarium. He brings his cousin Kathy some lunch his mom has ready (a technique to instantly make the hometown connections concrete) and mentions that Kathy has “simply opened a tax accounting service on the town, having left her job at a regulation agency that misplaced its main company shopper.” We’re getting the roles report in a brief burst of bullets. Kathy, “one of many least neurotic, most industrious folks” Indiana is aware of, reminds him how a lot all of them needed to flee the manufacturing unit life. After noting his “class hatred” of “New Hampshire yuppies” who fear about tree conservation, he clarifies: “I’ll by no means be wealthy sufficient to spend all day worrying about acid rain and printing brochures about it on recycled paper.”

Indiana has little frequent trigger with the take-meisters as a result of his tales are fairly extensive in emotional tone, rooted each in his expertise and a political conscience. As heartbreaking as the problems of 1992 may very well be, they have been all episodes in one other infinite battle: class battle. The current quote that has caught with me is a remark he made to Tobi Haslett about Ulrike Meinhof in his “Artwork of Fiction” interview for the Paris Evaluate: “Having 1,000,000 opinions about every thing comes low cost and simple, whereas really doing one thing can price you quite a bit.”

It’s the inescapable density of life that propels Indiana, a way that have deserves to be written about, but in addition that writing should not dissolve into the weak gasoline of opinion. In a bit on Masha Gessen’s e book on the Tsarnaev brothers, Indiana drops a touch upon the state of executions that takes the bodily into consideration as a lot it traces the political. “In current Ohio, Arizona, and Oklahoma executions,” Indiana writes, “a European export embargo on deadly injection medicine has prompted combine ’n’ match improvisations with untested prescription drugs, with outcomes Josef Mengele would contemplate plagiarism.” Indiana’s work is delicate to the endlessness of the sensation throughout the endlessness of the ache. Issues really occur—life isn’t a wacky accretion of characters who conveniently embody that week’s mental whims. Executions harm like hell and cash adjustments every thing. For somebody who acquired so used to pillorying the moneyed within the artwork world, it’s telling that he begins Andy Warhol and the Can that Bought the World (2010) by noticing the artist’s “work’s virtually surreal monetary appreciation.” That appears a minor line however it’s not. To recollect, repeatedly, the true that defines the surreal is an virtually insufferable burden, and in addition the rationale to write down, for Indiana.

Maddeningly, it’s not indicated in Fireplace Season the place the essays have been first printed, so I can’t let you know what “Romanian Notes” is or why it exists. (It appears to be Indiana roaming round Bucharest and taking notes.) Amid a attractive foray in a carpet store, Indiana is considering battle and surveillance and the American love of a very good coup. I get pleasure from his descriptions of the service provider Ahmet, who “had a Wagnerian opera’s price of rug chat saved in an in any other case fallow mind,” however I’m reassured by Indiana the preacher, calling the demon sprawl of bureaucracies “glue traps for federal income.” I’m pondering of the DHS’s federal police thrashing pro-abortion protesters in LA in early Could, begging the query of what precisely homeland safety was being threatened. As at all times—the cash. “The overriding crucial of any paperwork funded by the state is its personal self-perpetuation,” Indiana writes from Bucharest. Particularly, “an anti-terrorism company will breed its personal terrorists, attracting weak-minded, probably risky folks into bogus conspiracy cells.” As quickly as I discover myself desirous about folks being kettled and clubbed for caring concerning the lives of girls, I discover myself desirous about how Indiana would report it. Who higher to write down concerning the functionaries who see our bodies on the road as a chance to divert billions for armored autos and technical athleisure?

That sense of occasions at all times representing a political commingling is on the coronary heart of his 1991 piece on Oliver Stone’s JFK. “Like a lot of recent life unanticipated by the Structure, the saturation reserving of two thousand theaters for a single director’s model of Gandhi or Jesus Christ or the taking pictures of JFK is one thing we simply need to dwell with, together with the straightforward buy of Uzis and AK-47s.” So many editors would beg Indiana to take away that final phrase. You possibly can think about the Google Doc observe: “Completely perceive the temper, because it’s an assassination pic, however it appears redundant? And JFK wasn’t shot with both of those weapons. Maybe reduce for size?” However these simple purchases have trebled since 1991, and we now dwell in a world the place presidential assassinations really feel someway lackluster. Three presidents killed concurrently with robotic shrimp? That may be a film. Or a information merchandise. Hopefully Indiana will write that column.

One among my favourite items is on Renata Adler’s novels, Speedboat and Pitch Darkish, and which, it so occurs, appeared in these pages. Unpredictable books written by a predictably lauded author is strictly the form of factor to throw Indiana at, and he spots the miraculous twist of those books of their use of first individual. He additionally, it appears, spots himself. The tales in Speedboat “convey a category solidarity that has much less to do with cash than with training and an curiosity in politics and tradition, a good diploma of social polish (typically noticed within the breach), and moral scruples that preclude sure types of success and facilitate others.” Indiana notes that Jen Fain, the writer-narrator of Speedboat, a novel “unfettered by plot,” is a model “of Renata Adler by Renata Adler,” which he defends as “barely outstanding.” (He appears to really feel the necessity to defend a fellow mosaicist.) Indiana snaps on the “thought particles” of the web, the place phrases like “experimental” are used to explain Adler’s novels not as a approach of taking “enjoyment of all literary kinds” however as “filtering screens for the literary market, which is presently dominated by aesthetic conservatism of a depressingly conformist ilk.” That Indiana wouldn’t discover fellows on the web isn’t outstanding, both. I like Indiana’s kicker right here, that Adler’s novels are helpful as a result of they inform us “what it’s wish to be residing now, throughout this span of time, in our specific nation and our specific world.” He likes writers to kick in opposition to bourgeois pruderies and their accommodationist love of style, that which may be most simply offered. (The exurban proximity within the early twenty-first century of McMansions and Barnes & Noble retailers springs to thoughts.) The important thing line is one which Indiana quotes, a bit of one in all Jen Fain’s monologues: “I don’t assume a lot of writers in whom nothing is in danger.” Indiana’s popularity as imply is such an odd categorization for somebody who’s so able to feeling the struggles of his topics, to see their danger as his personal.

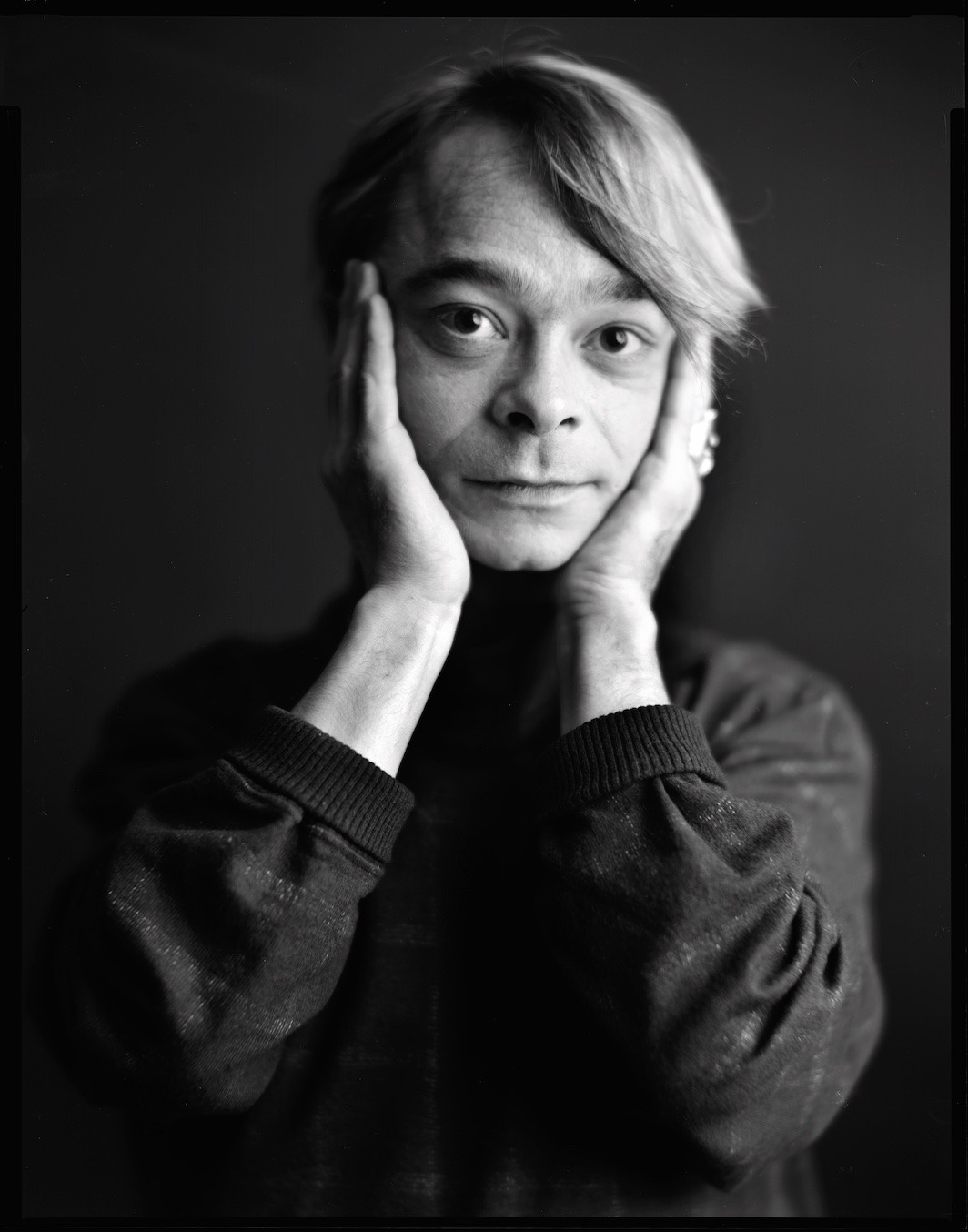

Sasha Frere-Jones is a author and musician residing within the East Village. He not too long ago accomplished a memoir.