‘Philosophical theories are way more like good tales than scientific explanations.’ This provocative comment comes from the paper ‘Linguistic Philosophy and Notion’ (1953) by Margaret Macdonald. Macdonald was a determine on the institutional coronary heart of British philosophy within the mid-Twentieth century whose work, particularly her views on the character of philosophy itself, deserves to be higher identified.

Early proponents of the ‘analytic’ technique in philosophy similar to Bertrand Russell noticed good philosophy as science-like and had been dismissive of philosophy that was overly poetic or unscientific. Russell, for instance, took situation with the French thinker Henri Bergson, who was one thing of a bête-noire for early analytic philosophers. Bergson’s theorising (Russell thought) didn’t depend upon argument however slightly on expressing ‘truths’, so-called, arrived at by introspection. As Russell wrote in ‘The Philosophy of Bergson’ (1912):

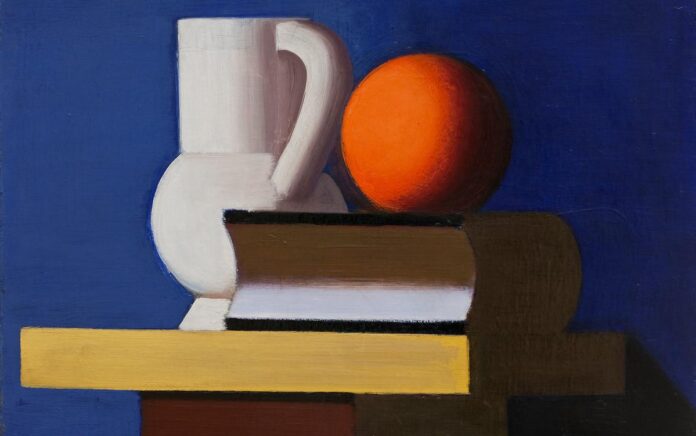

His imaginative image of the world, considered a poetic effort, is in the primary not able to both proof or disproof. Shakespeare says life’s however a strolling shadow, Shelley says it is sort of a dome of many-colored glass, Bergson says it’s a shell which burst into elements which can be once more shells. Should you like Bergson’s picture higher, it’s simply as authentic.

Russell locations Bergson alongside William Shakespeare and Percy Bysshe Shelley and worries that there isn’t any goal measure of whose worldview is extra correct. There’s no approach of proving which is a greater account of issues, it’s merely a matter of which ‘picture’ you want finest. In different phrases, there’s no try to supply empirical proof – proof based mostly on publicly observable knowledge – in assist of those views. For Russell, this was sufficient to point out that what Bergson was doing was not likely philosophy, at the least not good philosophy, any greater than Shakespeare’s performs and Shelley’s poetry had been.

Russell’s view of what counts pretty much as good philosophy was not one which Macdonald shared. In her 1953 paper, she embraces comparisons between philosophy and literature, poetry and artwork. For Macdonald, philosophical theories are very very like ‘photos’ or ‘tales’ and, maybe much more controversially, she means that philosophical debates typically come right down to ‘temperamental variations’. For instance, whether or not you might be prepared to imagine (in accordance with thinkers like René Descartes) that we’ve an immaterial soul will come right down to extra than simply the philosophical arguments you might be introduced with. Your view on this matter, Macdonald thinks, will extra doubtless be decided by your personal private values, life experiences, faith and so forth. On this approach, she thinks, temperamental variations account for a lot of philosophical disagreements.

Nonetheless, in contrast to Bergson, Macdonald was not working in a special philosophical custom from Russell. She was, to all appearances at the least, simply as a lot part of analytic philosophy as he was. The truth is, institutionally, she was on the very centre of issues. Macdonald studied on the College of London and her PhD was supervised by Susan Stebbing, the primary girl in Britain to be appointed a full professor of philosophy. Together with Stebbing and others together with Gilbert Ryle, Macdonald helped discovered Evaluation – the educational journal of analytic philosophy – which she later edited after the Second World Struggle. And all through the Thirties and ’50s, she printed many articles in venues just like the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, the UK’s foremost philosophical society, and was an lively member of Cambridge College’s Ethical Sciences Membership.

So what occurred? How did Macdonald find yourself with such a special view about what good philosophy appears to be like like from Russell’s? And, if Macdonald was proper, what does that suggest in regards to the worth of philosophy?

The story of Macdonald’s entry into philosophy is sort of outstanding. She was born in 1903 into poverty to a single mom who later absconded to Australia, leaving her child behind to be fostered. Macdonald was unwell all through her childhood and youth, affected by tuberculosis (amongst different issues), and supported by an organisation referred to as the Nationwide Youngsters’s House and Orphanage that later helped pay for her undergraduate research. As Michael Kremer notes, Macdonald’s upbringing stands in stark distinction with most of the canonical figures in Twentieth-century philosophy similar to Russell, who was born into British aristocracy (his grandfather was an earl who was twice prime minister), Ludwig Wittgenstein, a member of what was, traditionally, an especially rich household (his father Karl, an industrialist, was one of many richest males in Europe), or Ryle, who spent his complete grownup life simply transferring via the ranks on the College of Oxford.

Stebbing was an necessary determine in Macdonald’s life, each personally and professionally. Macdonald was one in all quite a few ladies who benefitted from Stebbing’s supervision, together with Ruth Lydia Noticed and Elsie Whetnall, and would go on to show at Bedford School (now a part of Royal Holloway, College of London) the place Stebbing was professor of philosophy.

It was not straightforward for ladies to determine themselves in philosophy at the moment and many ladies’s careers had been negatively impacted by sexism (Oxford didn’t bestow levels to ladies till 1920, and on the College of Cambridge it even later: 1948). When she utilized for G E Moore’s Chair in Cambridge in 1938, Stebbing, for instance, was informed by Ryle that ‘everybody thinks you’re the proper individual to succeed Moore, besides that you’re a girl’. Blunt to say the least. Equally, in a letter to a pal in 1939, Macdonald writes: ‘I’ve been hoping to get a everlasting lectureship in philosophy … It’s troublesome in my topic, particularly for a girl.’ Nonetheless, via a pipeline from Bedford School into educational philosophy (and infrequently again to Bedford School), Stebbing was capable of assist a number of ladies set up themselves within the occupation.

She topics philosophical enquiry itself to scrutiny, analysing the ways in which philosophers speak and write

It’s also doubtless that Stebbing had a hand in pushing Macdonald to give attention to the connection between philosophy and language. In Considering to Some Function (1939), Stebbing emphasises the significance of distinguishing between completely different makes use of of language – eg, the distinction between descriptive and emotive language – not solely in philosophy, however in public discourse similar to politics and journalism. After working with Stebbing, Macdonald went to Cambridge to work on a venture on the affect of language on the idea of ‘matter’, a subject on which Stebbing herself as soon as deliberate to write down a e book.

Quickly after arriving in Cambridge within the Thirties, Macdonald met Wittgenstein, a towering determine in Twentieth-century philosophy. Together with Alice Ambrose, Macdonald attended a lot of his lectures – and the 2 ladies would go on to publish the so-called Blue and Brown Books, collated from notes they took between 1932-1935. It’s no coincidence that, from the late Thirties onwards, Macdonald’s work typically attracts on what is named ‘linguistic evaluation’ – which is an strategy to philosophy slightly than a selected idea. Linguistic evaluation was central to Wittgenstein’s later philosophy (and necessary in Ambrose’s philosophy, too).

Linguistic evaluation includes being attentive to and drawing conclusions from the language utilized in explicit contexts, together with philosophical debates, scientific theories, and odd (common sense) language. In her essay ‘Linguistic Philosophy and Notion’, Macdonald topics philosophical enquiry itself to scrutiny, analysing the types of ways in which philosophers speak and write – particularly as compared with scientists. This type of linguistic evaluation is a approach of taking a step again and having a look on the observe of philosophy itself. It includes answering questions like: What do philosophical disagreements contain and what do philosophical theories appear to be?

In a way, then, Macdonald’s goals will be considered anthropological: she is excited about making observations about what a specific subsection of society – philosophers – are doing and offering an outline of their actions. Macdonald takes philosophers of notion as her case research (therefore the paper’s title) and, by being attentive to the language they use, presents an account of what philosophy of notion actually quantities to. Though, as we’ll see, her findings stretch past simply philosophy of notion, they embrace the character of philosophy itself.

Putting the instruments of linguistic evaluation to work, Macdonald focuses her consideration on the phrase ‘idea’. What do philosophers imply once they discuss philosophical ‘theories’? And is it the identical factor that scientists imply when they use the phrase ‘idea’? Macdonald’s reply is a categorical ‘No’.

She claims that, when scientists put ahead theories, they achieve this to elucidate empirical information. Scientists put ahead hypotheses (eg, ‘Earth is spherical’ or ‘bodily objects are ruled by legal guidelines of gravity’), which might then be verified (or falsified) by experiments and observations, forsaking solely believable theories, and eliminating these which can be refuted by factual proof. Thus, Macdonald writes: ‘Affirmation and refutation by truth is an important a part of the that means of “idea” in its empirical sense.’

If ‘affirmation and refutation by truth’ based mostly on experiments is important to the way in which that the phrase ‘idea’ is utilized by scientists, that gives a foundation on which to look at whether or not philosophers use the phrase ‘idea’ in that approach. And that is the place Macdonald thinks philosophical theories differ from what scientists imply by the time period:

They can’t be examined. Each philosophical idea of notion is appropriate with all perceptual information.

In accordance with Macdonald, philosophical theories can’t be examined. Is that true? What would possibly she imply by this? As soon as once more, she makes use of the philosophy of notion as her instance.

Philosophical theories, in contrast to scientific theories, are usually not within the enterprise of discovering new information

Two opposing positions within the philosophy of notion are direct realism and oblique realism (I’m going to oversimplify each right here). Direct realism is the view that we straight understand exterior objects on the planet round us. Once I look out of my window, I straight see a tree – and the character of my perceptual expertise informs me (straight) in regards to the nature of the tree. Oblique realism, then again, is the view that I solely ever not directly understand objects like timber. What I straight understand are psychological representations – ie, concepts of timber – which can be produced in my thoughts when my sense organs (eg, my eyes) are stimulated in the precise approach and ship indicators to my mind. I study in regards to the world round through these concepts (often known as ‘sense knowledge’) in my thoughts. Direct realism might sound extra common-sensical, however oblique realism might sound higher outfitted to take care of the existence of illusory or hallucinatory experiences, the place I’m seemingly not perceiving the world the way in which it truly is. Given all this, isn’t it true to say that direct realists and oblique realists disagree on the information?

In a way, sure. However Macdonald’s level is that there isn’t any disagreement on the phenomenological information: information about what it’s wish to have a perceptual expertise. Each the direct realist and the oblique realist agree that, once I look out my window, I see a tree. What they disagree on is what it means to say that ‘I see a tree’ – they disagree on the mechanics of what’s going on, or how finest to elucidate the truth that I see a tree. Most significantly, for Macdonald, there’s no empirical take a look at out there to attract a line between the 2 theories. We are able to’t run an experiment to check for the reality of both idea as a result of, on the extent of expertise, each events agree that it’s true to say: ‘I see a tree.’

Thus, step one in Macdonald’s meta-philosophical argument is to point out that philosophical theories are not ‘theories’ in a scientific sense since they lack the important criterion of being confirmed or refuted by truth. Because of this, she argues, philosophical theories, in contrast to scientific theories, are usually not within the enterprise of discovering new information.

So what’s it that philosophical theories do? Macdonald’s reply is: ‘What they do counsel are new types of expression for acquainted information.’

At this level, Macdonald’s evaluation of the worth of philosophy takes a flip that will have made Russell – who tried to maneuver philosophy as far-off from the humanities as attainable – very uncomfortable. Macdonald claims that philosophy’s worth is way nearer to that of artwork, literature or poetry than science. She explains that the humanities inform us that ‘Language has many makes use of in addition to that of giving factual info or drawing deductive conclusions.’ A philosophical idea could not present ‘info in a scientific sense’, she writes, ‘however, as poetry exhibits, it’s removed from nugatory.’

By this level in her profession, Macdonald had engaged extensively with the philosophy of artwork, the philosophy of artwork criticism, and the philosophy of fiction. Her meta-philosophical claims in ‘Linguistic Philosophy and Notion’ point out that her engagement with the humanities gave her an acute sense of the place their worth lies. What’s extra, she evidently got here to imagine that the worth of philosophy may be very comparable.

A great work of poetry, artwork or literature, Macdonald explains, can ‘enlarge’ sure elements of human life to assist us see and take into consideration them otherwise. For instance, Shakespeare’s Othello encourages us to consider jealousy by making it the centrepiece of the play. Or take into account the emphasis on humanity’s relationship with nature in Romantic poetry. In each circumstances, the artist has ‘zoomed in’ on, or ‘enlarged’, a facet of life – in a approach that it’s not usually enlarged in actual life – to encourage the viewers to mirror on it.

Hers is a 180-degree flip away from the ‘scientistic’ account of fine philosophy Russell endorsed

Macdonald’s declare is that philosophical theories act in an identical approach – completely different theories ‘enlarge’ sure elements of expertise. And this, in flip, signifies that the proponents of these theories find yourself telling competing tales. Some philosophers, like Plato, emphasise the diploma to which our senses deceive us. Others, like Aristotle, emphasise the diploma to which sense-experience is essential to information. Once more, Plato and Aristotle didn’t disagree on the information of expertise – each agree that once I look out the window, I see a tree. However they disagree in regards to the type of story we ought to inform about these information. In Plato’s story, the senses are the villains. In Aristotle’s, they’re the heroes. Thus, Macdonald writes:

Everybody, it’s generally mentioned, is born both somewhat platonist or somewhat aristotelian. No matter be the reality of this aphorism has little to do with the reality and falsity of those doctrines. It refers slightly to temperamental variations.

What we discover in Macdonald’s meta-philosophy, then, is a 180-degree flip away from the ‘scientistic’ account of fine philosophy that Russell endorsed. Russell nervous that selecting between Shakespeare, Shelley or Bergson would possibly develop into merely a matter of particular person choice, that there can be no criterion for exhibiting that one was a greater thinker than one other. However Macdonald’s declare is that that is true of any philosophical idea – completely different tales will go well with completely different temperaments.

At this level, one would possibly suppose: sufficient is sufficient. It’s all very nicely to think about how philosophy overlaps with the humanities, however absolutely Macdonald has gone too far when she means that philosophical theories are simply ‘good tales’. Extra formally, one would possibly fear that Macdonald’s account of philosophical debate generates an issue of relativism.

If philosophical debates come right down to ‘temperamental variations’, then it appears to be like like there’s no actual proper or improper (or true or false) – any greater than it’s proper or improper to desire John Keats to Shelley, or Sally Rooney to James Joyce. Macdonald herself articulates the priority like so: ‘Ought not philosophy to be impersonal, unemotional and strictly rational?’

This leaves Macdonald with two choices. The primary is to chunk the bullet and settle for that, since inventive judgments are relativistic, and philosophy is like the humanities, then philosophical preferences have to be relativistic too. However there’s one other response out there to Macdonald that doesn’t contain accepting the cost of relativism. Observe that the road of reasoning above relies upon upon a vital assumption: that inventive judgments are relativistic.

Is that this actually true? Are judgments about artwork, literature and poetry purely a matter of subjective preferences? Some could be tempted to reply ‘Sure’. If I like my youngster’s hand portray greater than a bit hanging in Tate Trendy, I could be inclined to say that, for me, it’s a higher piece of artwork. Equally, if I get extra enjoyment studying Rooney’s novel Regular Individuals than Joyce’s Ulysses, then who’s to say that Joyce is a greater author.

For Macdonald, the job of an ethical thinker is akin to that of an artwork critic

Nonetheless, elsewhere in her writing – eg, her essay ‘Pure Rights’(1947) – Macdonald endorses the view that, whereas inventive judgments can’t be empirically examined – and thus ‘falsified’ or ‘verified’ like scientific hypotheses – they are often defended and justified. An artwork critic can justify their judgment that one piece of artwork is healthier than one other. And so they can persuade others to agree with them, and minds will be modified. In that sense, Macdonald suggests, a critic is sort of a barrister, pointing to sure proof and telling a narrative supposed to win over the jury to a specific standpoint. In different phrases, inventive preferences are usually not totally relativistic.

Think about a case wherein you learn a novel and discover it underwhelming – it didn’t seize your creativeness or have interaction you. However later you communicate to a pal who explains how the novel alludes to sure literary tropes, or subverts the style in some distinctive approach, or satirises a political motion you had been unaware of. You would possibly discover that your thoughts has modified. Your consideration has been drawn to options of the novel and, to borrow Iris Murdoch’s phrases, you’ve gotten been compelled to ‘look once more’.

In ‘Pure Rights’, Macdonald argues that moral judgments (eg, ‘homicide is improper’ or ‘it’s improper to steal’), whereas they don’t seem to be empirical in similar approach that scientific hypotheses are – they can’t be examined by experiment – are nonetheless significant. And, once more, she attracts on judgments in regards to the arts as a mannequin for what significant, however non-empirical, statements would possibly appear to be. For Macdonald, the job of an ethical thinker is akin to that of an artwork critic: each are within the enterprise of defending or justifying sure judgments or preferences. It’s not, as Russell says, so simple as liking one picture greater than one other. There’s an onus on having the ability to justify or rationalise that choice.

The fear would possibly persist that absolutely there’s the matter of reality to deal with. Philosophical theories could be like good tales, however absolutely solely a kind of tales will be true, or at the least nearer to the reality than one other? Macdonald doesn’t handle this query head-on so it isn’t apparent what her reply can be. I’ve tried to point out that her view is that even our particular person preferences will be defended or justified, similar to artistic endeavors, that means that our philosophical views needn’t purely come right down to mere intestine intuitions. However I’m tempted to counsel that Macdonald wouldn’t be overly involved about reality – at the least not in the way in which we normally consider it. Different students, like Cheryl Misak, have related Macdonald to pragmatist philosophers like Frank Ramsey. Pragmatism, in a nutshell, is the view that what’s true is what’s helpful. And completely different philosophical theories will be helpful to completely different folks for various causes (similar to, Macdonald would possibly add, their temperament). Whereas it’s under no circumstances express, the relativistic bent to Macdonald’s account of philosophical theories would possibly sign that she was influenced by pragmatist methods of fascinated with reality.

While Russell’s comparability between Bergson’s philosophy and the writings of Shakespeare or Shelley is meant as a type of criticism, Macdonald argues that an appreciation of the humanities is essential to understanding the place the worth of philosophical enquiry lies. The truth is, Macdonald argues that philosophers should cease making an attempt to make scientific philosophy a factor – as a result of it’s harmful for philosophy. As long as philosophers like Russell sustain the pretence that philosophy should be like science, they’re judging it by an ordinary that it can not hope to satisfy – exactly as a result of philosophical ‘theories’ aren’t empirically testable.

However Macdonald’s makes an attempt to push philosophy away from science and in the direction of the humanities isn’t only a defensive manoeuvre. It’s additionally, she thinks, a approach of creating the worth of philosophy clearer. For Macdonald, philosophy’s worth lies not in offering us with new information in regards to the world, however slightly in serving to to see the acquainted in a brand new mild, in drawing consideration to options of expertise that may ordinarily move us by, and by offering us with tales that may assist make higher sense of the world round us. Whether or not her story about what philosophy is is healthier than Russell’s story, or only a completely different story, nicely, that’s as much as you to resolve.