Tony Johnson sits on his mattress along with his canine, Sprint, within the one-room residence he shares along with his spouse, Karen Johnson, in a care facility in Burlington, Wash. on April 13, 2022. Johnson was one of many first individuals to get COVID-19 in Washington state in April of 2020. His left leg needed to be amputated as a result of lack of wound care after he developed blood clots in his toes whereas on a ventilator.

Lynn Johnson for NPR

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson for NPR

Tony Johnson sits on his mattress along with his canine, Sprint, within the one-room residence he shares along with his spouse, Karen Johnson, in a care facility in Burlington, Wash. on April 13, 2022. Johnson was one of many first individuals to get COVID-19 in Washington state in April of 2020. His left leg needed to be amputated as a result of lack of wound care after he developed blood clots in his toes whereas on a ventilator.

Lynn Johnson for NPR

It did not take lengthy for the pandemic to reach on Whidbey Island. That pastoral slice of the Pacific Northwest meanders by means of the higher reaches of Puget Sound, coming inside simply 30 miles of downtown Seattle. It was this nook of the nation that alerted People to the truth {that a} virus does not abide by worldwide borders and a world pandemic had made landfall within the U.S.

The very first confirmed case of COVID-19 within the U.S. was right here, in Washington state. And by early March of 2020, the virus had torn by means of a nursing residence in a quiet suburb on the jap edges of Lake Washington. That outbreak marked a few of the very first identified U.S. deaths of the pandemic. As ambulances shuttled these sufferers to a close-by hospital, the remainder of the nation was left to surprise: When would these scenes of panic and illness attain their hometowns, their hospitals, their mother and father, siblings and spouses?

Cindy Holland, Aundrea Jeter and Myca Dauz look ahead to sufferers on the testing tent constructed and run by Whidbey medical workers on April 15, 2020. The crew wears layers of protecting gear to keep away from catching the virus.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Not lengthy after, the virus had caught a experience to Whidbey Island, residence to about 70,000 residents. And there, too, the each day rhythms of life modified virtually immediately. The place enjoys a wierd type of isolation. It runs 55 miles north to south and is counted among the many longest islands within the U.S. On the map, Whidbey might virtually go as a peculiar peninsula, suspended within the jumble of waterways and small islands that dot the area.

In actuality, although, it’s severed from the mainland. A strait, referred to as Deception Go, runs between Whidbey and neighboring Fidalgo Island, which practically touches the jap shores of the Sound. Apart from by air, there are solely two methods on and off: by taking a brief ferry experience; or braving a two-lane, metal bridge that soars 180 toes above the water earlier than depositing vacationers in a forest practically two hours north of Seattle.

The story of the coronavirus pandemic is commonly advised in extremes. An avalanche of sufferers overwhelming a hospital in New York. Refrigerated vans serving as makeshift morgues in Texas. Our bodies stacked to the ceiling at funeral houses in Florida.

Because the variety of COVID circumstances grew on Whidbey Island in 2020, the WhidbeyHealth Medical Middle hospital government crew tracked each day stats on a whiteboard of their disaster command heart. The numbers generally included the household and mates of hospital workers members.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Because the variety of COVID circumstances grew on Whidbey Island in 2020, the WhidbeyHealth Medical Middle hospital government crew tracked each day stats on a whiteboard of their disaster command heart. The numbers generally included the household and mates of hospital workers members.

Lynn Johnson

That’s not Whidbey Island.

As with in all places, individuals there have misplaced household, mates, jobs and futures. However those that take care of the group discuss of a extra refined, persistent erosion, one which’s jeopardizing the well-being of essentially the most susceptible.

WhidbeyHealth Medical Middle appears to embody this unfolding disaster. With 25 beds, the island’s solely hospital is on tenuous footing. The pandemic solely compounded years of economic stress. It is a acquainted predicament for well being care in rural America. Shedding the hospital can be dropping a lifeline. Sufferers must journey farther for life-saving care. Others can be left behind. That is what’s at stake for Whidbey Island on this precarious second.

Max and Finn Griswold climb ladders to speak to their grandmother, Mary Lee Griswold, throughout a go to by hospice nurse Myla Becker on June 5, 2020. Griswold spent her final days in hospice on the second ground of the Enso Home, a Zen retreat. Due to the pandemic, her household needed to discover inventive methods to be along with her throughout her last hours.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Jessica Leukhardt bathes a affected person in spring of 2020. Private protecting gear is a significant emotional and psychological barrier for residence well being employees to regulate to, particularly in caring for sufferers the place contact is so very important to their care.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Jessica Leukhardt bathes a affected person in spring of 2020. Private protecting gear is a significant emotional and psychological barrier for residence well being employees to regulate to, particularly in caring for sufferers the place contact is so very important to their care.

Lynn Johnson

When the virus first washed over the island, photojournalist Lynn Johnson was there. Now, two years and 1,000,000 deaths later, we return to see how the island and its persons are discovering their manner by means of the pandemic that has quietly however indelibly altered the place they name residence.

Tony Johnson, Longtime Island Resident

At first, Tony Johnson thought he’d emerged from a deep, deep sleep.

He did not know that only a week earlier the medical doctors had advised his spouse he’d probably by no means get up. He did not know the nurses had performed rock and roll for him whereas he was unconscious. He did not know that he’d quickly have to relearn easy methods to breathe and swallow. And he had no concept that COVID-19 would take much more from him than it already had throughout these 9 days on a ventilator.

Tony Johnson receives a blood transfusion on April 14, 2020 to deal with ongoing well being points ensuing from COVID-19. As a result of Whidbey is a crucial entry hospital, sufferers sometimes cannot keep longer than 96 hours, so nurses should not skilled to maintain individuals on ventilators for lengthy intervals of time. However nurses have needed to study new expertise to avoid wasting lives through the pandemic.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Tony Johnson receives a blood transfusion on April 14, 2020 to deal with ongoing well being points ensuing from COVID-19. As a result of Whidbey is a crucial entry hospital, sufferers sometimes cannot keep longer than 96 hours, so nurses should not skilled to maintain individuals on ventilators for lengthy intervals of time. However nurses have needed to study new expertise to avoid wasting lives through the pandemic.

Lynn Johnson

When he first moved to Whidbey Island greater than 20 years in the past, Johnson says it was a low-key place, populated by a bunch of “outdated hippies.” That appealed to him. So did the waterfront, the humanities and crafts truthful and the road dance that was held yearly. A few of that appeal could be very a lot alive there, however over time Johnson felt a shift. New individuals arrived, and so did builders. It grew to become costlier. His household might solely get by due to thrift shops and Walmart.

Ultimately, he and his spouse moved to Oak Harbor. It is a navy city on the north finish of the island with a buzzing naval base. After years of regular work, Johnson misplaced his job on the financial institution.

Karen Johnson’s husband of greater than 40 years, Tony, is within the hospital being handled for COVID. She is nervous with out him within the chair subsequent to her. The Johnsons are important employees who depend on public transportation, and had been unable to earn a living from home when the pandemic hit.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Karen Johnson’s husband of greater than 40 years, Tony, is within the hospital being handled for COVID. She is nervous with out him within the chair subsequent to her. The Johnsons are important employees who depend on public transportation, and had been unable to earn a living from home when the pandemic hit.

Lynn Johnson

“Out of the blue you end up remoted in a small group and there’s no work,” he says. “That made it actually robust.”

Just some years in the past, their cell residence was condemned. The water system was contaminated. Johnson had even fallen in poor health from an E. coli an infection. Later, his spouse fell by means of the decaying porch ground. She needed to be rescued by a neighbor.

In March of 2020, the virus gained a foothold within the Whidbey nursing residence, the place Johnson was residing on the time. Quickly he was one of many very first COVID-19 sufferers on the island. He was excessive threat, diabetic and over 60. By some means he survived, although he’d come off the ventilator with blood clots in his toes.

He was moved off the island as he recovered. However his wounds weren’t therapeutic effectively – weeks glided by with out anybody tending to them. An infection set in, consuming his toes and toes. A vascular surgeon was capable of restore blood move in a single leg. The opposite one couldn’t be salvaged, although. “They mentioned, ‘You’ll be able to both die from gangrene or we will amputate your leg,'” Johnson recollects. “It was not that onerous of a choice.”

Johnson says he does not miss the island a lot anymore. By then, his residence there was gone, only a graveled lot now. Nonetheless, he talks with exceptional ease about all that COVID-19 took from him. There are even some shocking flashes of humor. “You’ll be able to bury it deep or you possibly can simply let it out,” he says. “It is higher to let it out, so it does not eat you up the identical manner.”

Delores Jetton, hospice aide

There’s just one time when Delores Jetton refers to her work as a “job.” And it is when she tells you, “I really like my job.” In her heat voice, she speaks of it extra like a devotional observe — one she will solely carry out with deliberate fingers and unceasing curiosity. She bathes individuals, people who find themselves dying, at residence, in hospice. “Some make me chortle, some make me cry,” Jetton says. “I nonetheless love all of them the identical.” Working with the ageing has all the time appealed to her. In any case, they’ve one of the best tales. Her mantra? All it’s important to do is ask them one good query. “You higher make it rely,” she chuckles.

Chaplain Charlotte Keys holds an iPhone and blasts Gudrun Johnston’s favourite dance music, whereas Jetton takes her for a twirl to rejoice her birthday on April 23, 2020. Taking off their private protecting gear for the social gathering is an unusual exception to their typical routine.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Chaplain Charlotte Keys holds an iPhone and blasts Gudrun Johnston’s favourite dance music, whereas Jetton takes her for a twirl to rejoice her birthday on April 23, 2020. Taking off their private protecting gear for the social gathering is an unusual exception to their typical routine.

Lynn Johnson

The intimacy of her work underwent a wierd transformation through the pandemic. Out of the blue, she was shrouded, head to toe with a robe, gloves and masks. Individuals would generally ask to see her face. She’d end bathing them, step exterior and peel off her layers. Then she’d stand at their window and smile. Others do not care about seeing her face. They merely need to really feel her hand on their arm or have her rub their toes.

Delores Jetton rigorously bathes Elvy Kaik throughout a hospice go to on April 23, 2020. As a result of their work is so hands-on, Delores and different residence well being care employees on Whidbey Island put on intensive gear and take additional precautions to attenuate COVID threat.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Delores Jetton rigorously bathes Elvy Kaik throughout a hospice go to on April 23, 2020. As a result of their work is so hands-on, Delores and different residence well being care employees on Whidbey Island put on intensive gear and take additional precautions to attenuate COVID threat.

Lynn Johnson

Jetton has spent a few years on the island. She moved there from Maryland as a result of her daughter was stationed on the base there. Her daughter left, however she stayed. The climate was good and so was the connectedness, a way that everybody is aware of one another even when they’re from totally different sides of the island: “I’ve but to run into any impolite individuals.”

Jetton has been a house well being care employee for many years. For the reason that pandemic began, she retains two bins behind her automobile —one with a bleach resolution and the opposite to rinse so she does not threat bringing COVID to her shoppers or again residence to her household.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Jetton has been a house well being care employee for many years. For the reason that pandemic began, she retains two bins behind her automobile —one with a bleach resolution and the opposite to rinse so she does not threat bringing COVID to her shoppers or again residence to her household.

Lynn Johnson

Earlier than Jetton enters the house of a brand new affected person, she pauses and says a prayer. She’ll inform you the fingers she makes use of to scrub individuals, people who find themselves on the sting of life, do not fairly belong to her. “I ask the Lord to steer me, to make me delicate to their wants and present me what you need me to do with them,” she says.

Tabitha Sierra, nurse supervisor

Tabitha Sierra does effectively throughout a disaster. She had studied public well being in California, after which went on to coach as an emergency trauma nurse. Ultimately, she’d discovered her strategy to Whidbey to take a job on the hospital. She favored the concept of her youngsters rising up on the island.

Cris Matocchi (left) holds Tabitha Sierra’s youngest baby on Might 28, 2020. Matocchi and Sierra have been tasked with testing greater than 3,000 individuals on the island.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Cris Matocchi (left) holds Tabitha Sierra’s youngest baby on Might 28, 2020. Matocchi and Sierra have been tasked with testing greater than 3,000 individuals on the island.

Lynn Johnson

The pandemic gave her readability of goal, a second to place her years of coaching in epidemiology to make use of. Masks, assessments and vaccines had been a part of her commerce. She knew the island was susceptible. It had a excessive focus of retirees and seniors, after which there have been the individuals residing on the margins, some even off grid.

So she started working, combing the island for anybody who wanted her: “There was a job to do and there was a solution: You helped individuals,” says Sierra.

Tabitha Sierra assessments a Whidbey Island resident for COVID in 2020. The pandemic gave her an opportunity to place her years of coaching in epidemiology to make use of.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Tabitha Sierra assessments a Whidbey Island resident for COVID in 2020. The pandemic gave her an opportunity to place her years of coaching in epidemiology to make use of.

Lynn Johnson

She remembers how the hospital stuffed up in these early days of the pandemic, when the virus unfold by means of the native nursing residence, only a stone’s throw away. “We had individuals who we might identified for a really very long time that had been coming in, they usually had been in our ICU,” she says. Those that did survive lingered there, even after they recovered, as a result of they merely “had nowhere else to go.”

Because the adrenaline light, Sierra began to note the ripple results of residing with COVID-19, the fraying internet of care and connection on the island. “People rely on hope. We get by means of issues, as a result of we all know on the opposite facet of them it will likely be okay,” she says. “I do not know that I hear loads of hope from individuals anymore.”

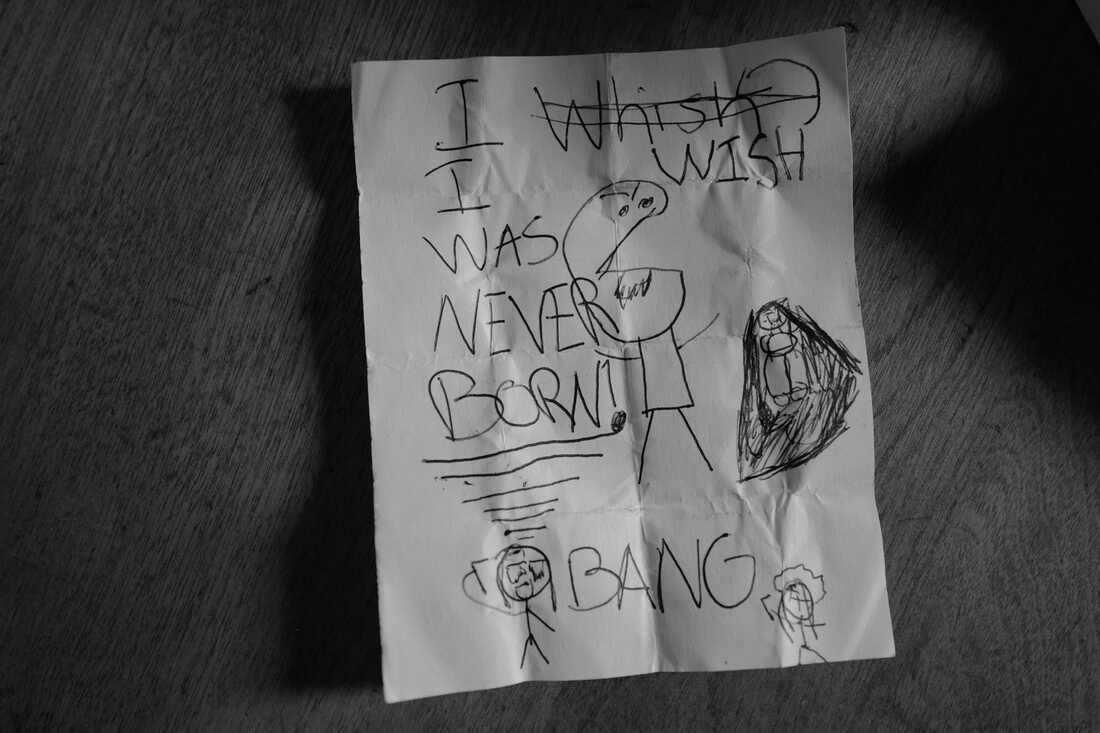

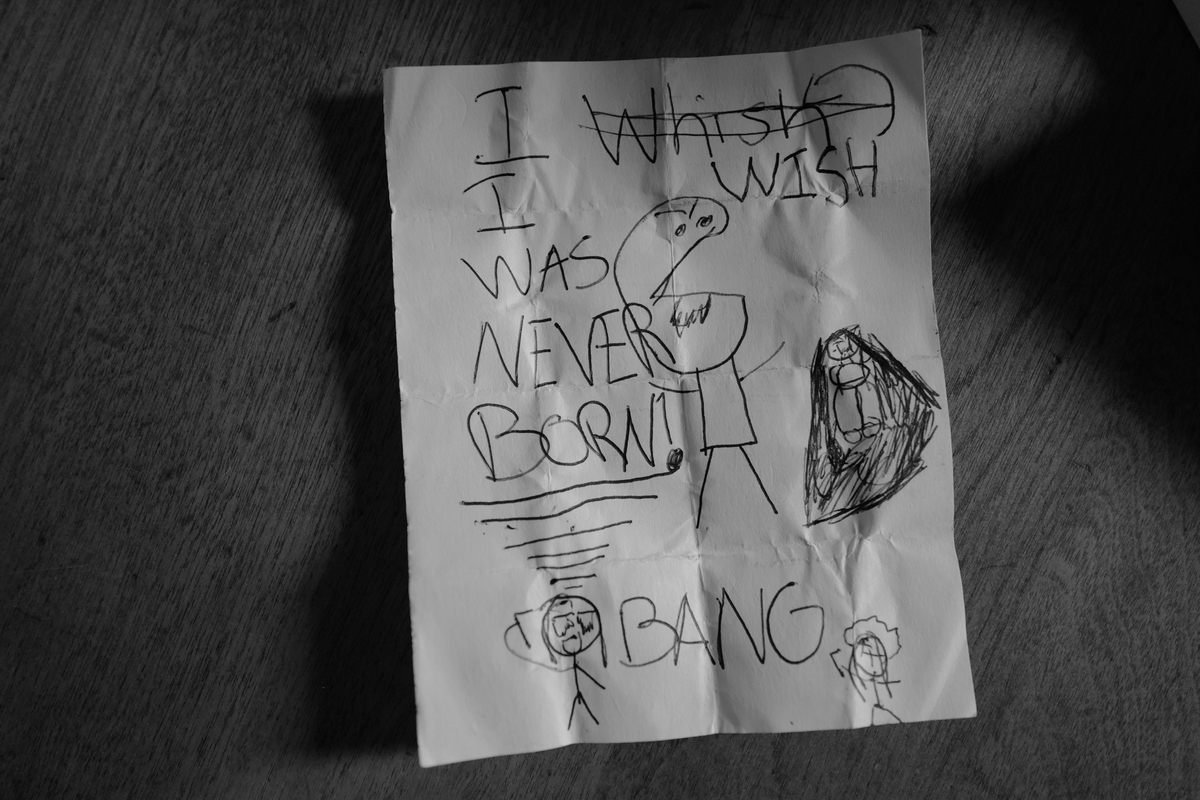

A pharmacy tech discovered a small folded notice written by a baby in a stairway of the Whidbey medical constructing within the fall of 2020. The opposite facet included a will. As a result of she has deep roots locally, Tabitha Sierra was capable of decide the kid’s id and dispatched a psychological well being counselor to the house.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

A pharmacy tech discovered a small folded notice written by a baby in a stairway of the Whidbey medical constructing within the fall of 2020. The opposite facet included a will. As a result of she has deep roots locally, Tabitha Sierra was capable of decide the kid’s id and dispatched a psychological well being counselor to the house.

Lynn Johnson

Well being clinics had closed. The pool of caregivers for the ageing and homebound shrank. And the hospital was struggling to remain afloat. Quickly there was discuss of slicing the labor and supply unit — the one one on the island — the place Sierra had taken over as nurse supervisor. If that occurred, there can be nowhere for a lady who was pregnant to get hospital care on the island.

Sierra imagined what would occur when issues went unsuitable — how valuable minutes can be squandered making an attempt to get off the island to the closest hospital. She did the mathematics: no less than 4 infants would have died up to now 12 months alone, and “in all probability extra moms than that, if we had not been right here proper after they wanted us.”

For now, labor and supply stays open. The hospital directors say they’ve backed off from the concept, after contemplating the repercussions. However with cash tight, nothing is definite fairly but.

Doug Neal, paramedic

Out of the blue, all of the calls appeared to simply cease. Doug Neal wasn’t fairly certain what to make of it. He had labored on the island for greater than 20 years as a paramedic. “The streets had been naked,” says Neal. “Hardly ever did we roll out.”

Doug Neal tries to calm a affected person in an ambulance in Might of 2020.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Doug Neal tries to calm a affected person in an ambulance in Might of 2020.

Lynn Johnson

The lockdown — and the specter of catching the virus — had saved even a few of the sickest individuals from calling 911 in these early days of the pandemic. Many had medical issues that went untended, generally for months or longer. Ultimately, Neal would see these sufferers. After which it could be a real emergency: “As an alternative of calling earlier, after they know that they are going to want some assist, they’d name too late, generally.”

Neal’s glove was shredded after a tough experience within the ambulance spent making an attempt to regulate a younger girl they picked up exterior of her good friend’s condo in Might of 2020.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Neal’s glove was shredded after a tough experience within the ambulance spent making an attempt to regulate a younger girl they picked up exterior of her good friend’s condo in Might of 2020.

Lynn Johnson

All that had modified by the second 12 months of the pandemic. Calls began pouring in. In 2021 alone, his emergency medical providers crew transported 1,000 extra individuals than ever earlier than. “That is simply an astronomical quantity,” he says.

A few of the sufferers had COVID; others had been scared they did and did not know the way else to get a solution. Today, he is spending loads of time merely searching for a spot to carry his sufferers. Generally the hospitals do not have sufficient nurses on workers, or the fitting gear, or sufficient beds. “You are on the cellphone making an attempt to determine the place to take somebody and all people’s saying, ‘No, we’re full. We won’t take it.’“

Whidbey solely has so many ambulances. A journey off the island to the closest hospital can take no less than half-hour, in case you’re working lights with sirens blaring. The extra ambulances that depart the island seeking a hospital, the less persons are left to take care of these nonetheless there. “It occurs, at occasions, once we’re all busy on calls, and there is not one other rig accessible.”

Richard West, therapist and disaster responder

Richard West is aware of he cannot get away from his work — not that he needs to. Perhaps, it will occur on the grocery retailer or a gasoline station. “We’re in a small group and the probabilities of us sharing the identical area is actually excessive,” he says. Invariably, he’ll run into somebody he is handled as a therapist and disaster responder. That is the truth of residing on Whidbey Island, a spot the place the necessity for psychological well being care eclipses the providers truly accessible. However that is partly why he is there. The small city really feel works for him. Generally it even reminds West of the place he grew up in Oklahoma, as a tribal member of the Muscogee Creek Nation.

Sierra (left) and Richard West (proper) meet with a affected person at residence on June 1, 2020. West is a psychological well being outreach counselor for Island County, which incorporates Whidbey and Camano islands. West’s mother and father died from COVID-19 in 2020.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Sierra (left) and Richard West (proper) meet with a affected person at residence on June 1, 2020. West is a psychological well being outreach counselor for Island County, which incorporates Whidbey and Camano islands. West’s mother and father died from COVID-19 in 2020.

Lynn Johnson

Earlier than turning into a therapist, West spent years as a probation and parole officer. When he moved to the island, he noticed that generally there can be nowhere to ship individuals who wanted psychological well being remedy. In the event that they wished assist, they’d usually have to go to Seattle. That meant some individuals did not get any assist in any respect. So, he determined to open up his personal observe. If individuals have to see him, perhaps due to a court docket order or a disaster, he tries to see them, even when they cannot pay. And when the pandemic got here to Whidbey, West did not go distant. He stayed on the market — doing what he does greatest: connecting with individuals, speaking them down, discovering them assist. Generally he’d tag together with cops, making an attempt to prop up the fraying security internet in his group.

West is the caseworker for Phil and Angela Pennington (left), and their 16-year-old daughters, Chloe (proper) and Sophia (not pictured), who each have autism. The household is struggling because the pressures of COVID and rural isolation mount.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

“I’ve simply seen a lot grief and concern and uncertainty,” he says. “That simply causes some individuals to type of unravel on the seams.” There’s one affected person he remembers who’d labored with him for a number of years. Someday, that particular person killed themself. Others died by overdose. “Those that already had some struggles, it simply grew to become magnified,” he says.

West helps George Bulldis, photographed on Jan. 19, 2021, transition into a house. Psychological well being, housing and meals sources are stretched skinny due to COVID so getting help takes for much longer than normal or is just unavailable.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

West helps George Bulldis, photographed on Jan. 19, 2021, transition into a house. Psychological well being, housing and meals sources are stretched skinny due to COVID so getting help takes for much longer than normal or is just unavailable.

Lynn Johnson

Even now, West feels the tailwinds of the pandemic in his personal observe: “Persons are just a bit extra indignant and a little bit extra on the sting, and even a little bit extra unforgiving.” Household ties are strained or shattered. And the island’s capability to reply is flagging. The psychological well being infrastructure has withered. Clinics and counselors shut down due to COVID-19. Some have by no means reopened. West tries to fill within the gaps. “I simply attempt to be a person of my phrase and provide what we will,” he says. “There are such a lot of that are not getting any assist.”

Peyton Wischmeier and Chrysalis Kendall, speech therapist, occupational therapist

Speech therapist Peyton Wischmeier wears two clear masks in November 2020 so she will shield herself however the youngsters she works with can nonetheless see her mouth. To start with of the pandemic, a few of her sufferers had been afraid of her. Wischmeier is just lately again from maternity depart and takes additional precautions so she doesn’t carry COVID residence to her new child.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Speech therapist Peyton Wischmeier wears two clear masks in November 2020 so she will shield herself however the youngsters she works with can nonetheless see her mouth. To start with of the pandemic, a few of her sufferers had been afraid of her. Wischmeier is just lately again from maternity depart and takes additional precautions so she doesn’t carry COVID residence to her new child.

Lynn Johnson

Peyton Wischmeier has all the time had a waitlist. There are few different choices on the island for households who want a speech therapist, particularly if they do not have a lot cash or good medical insurance. She does not have that drawback. WhidbeyHealth Medical Middle is a public hospital, so she will take anybody, no matter what they’ll pay. That is a very good factor, however it leaves Wischmeier with a way that she will by no means get to everybody as quick as she’d like, or perhaps in any respect: “It looks like if I’m unable to see a baby, different alternatives are simply actually nonexistent.”

Occupational therapist Chrysalis Kendall makes use of her cellphone to work with a baby on the autism spectrum who has bother specializing in April 24, 2020. Kendall has needed to be very inventive about altering her strategies and instructing surroundings so she will nonetheless see sufferers through the pandemic.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Occupational therapist Chrysalis Kendall makes use of her cellphone to work with a baby on the autism spectrum who has bother specializing in April 24, 2020. Kendall has needed to be very inventive about altering her strategies and instructing surroundings so she will nonetheless see sufferers through the pandemic.

Lynn Johnson

The pandemic has solely underscored how elementary it’s to have this one-on-one time. In a world of masks, visible cues are exhausting to come back by for youngsters who’re studying easy methods to transfer their mouths and make the fitting sounds. It is no shock they’re seeing an uptick in delayed speech expertise, says Chrysalis Kendall, an occupational therapist who works hand-in-hand with Wischmeier. “I name it a sensory hangover,” says Kendall, who moved to the island 5 years in the past.

Gabe Aguilera (left) has Down Syndrome and presumably autism. The isolation of COVID is a problem for him and his household. Peyton and Chrysalis (proper) work with Aguilera on the speech and occupational clinic. His mother and father are struggling along with his aggressive conduct.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Typically the youngsters who work with Kendall already wrestle with easy methods to interpret different individuals’s emotions. The pandemic was profoundly disorienting for them. “Out of the blue, all they’ll see are your eyes,” says Kendall, “and that for a child on the spectrum is the toughest place in your face to take a look at.” And it goes effectively past masks. Kendall nonetheless sees the aftershocks of all that social isolation and on-line studying. “Now we have these youngsters who actually depend on their exterior sources for regulation they usually’re unsure the place to go for that,” she says.

Lisa Toomey, oncology nurse

Lisa Toomey by no means downplayed the coronavirus, even when it was only a seemingly distant information story from abroad. It wasn’t her first pandemic. About 40 years in the past, Toomey confronted the HIV/AIDS disaster at first of her nursing profession. She nonetheless remembers the concern, how even some medical doctors and nurses would not contact their very own sufferers. With this new virus, Toomey wasn’t going to take any possibilities with these below her care. Their immune programs had been too fragile, suppressed from most cancers therapies. She says that is why her oncology unit, “the MAC” for brief, locked down earlier than the remainder of the hospital.

Oncology nurse Lisa Toomey and Dr. Amir Mehrvarz attempt to decide the reason for the intense ache that affected person Alcide Levac is experiencing on Nov. 6, 2020. Many most cancers sufferers delayed their therapies in concern of COVID, exacerbating illness markers and signs.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

Oncology nurse Lisa Toomey and Dr. Amir Mehrvarz attempt to decide the reason for the intense ache that affected person Alcide Levac is experiencing on Nov. 6, 2020. Many most cancers sufferers delayed their therapies in concern of COVID, exacerbating illness markers and signs.

Lynn Johnson

Quickly, it was just about unrecognizable. They’d all the time taken additional care to maintain their sufferers secure. Nurses would put on gloves and chemo robes, however COVID-19 ushered in a completely new manner of doing most cancers care. No extra hugging and holding fingers. Members of the family had been prohibited. The laughter and smiles appeared to fade. “We simply felt like we jumped over a cliff and we had been lower off from one another,” she says. “The lifeline was our masks and our gloves, that was our lifeline to proceed to carry onto each other.” Being on Whidbey meant they knew most of their sufferers, these had been their neighbors and mates. “We bought very, very protecting, and that is why nobody bought sick,” she says.

In these early days, Toomey says the oncology nurses made a pact: to maintain their sufferers secure, they must dwell like them. No touring. They hit the brakes on their social lives. Even Toomey’s circle of relatives was saved at a distance initially: “I might come residence and I did not hug my youngsters and my spouse for months.”

At work, the nurses would take care to not fall again into outdated habits. They’d eat lunch of their automobiles by themselves. Toomey had spent years instructing youthful nurses easy methods to do the job. Now she discovered herself studying once more. She found easy methods to provide that very same consolation to her sufferers, utilizing solely her eyes and tone of voice. And when vaccines arrived, she took on one more position: the “scheduling queen.” She booked numerous vaccine appointments for her sufferers.

Now, in the end, they’re lastly again to hugging. Members of the family have simply began to trickle in once more. Toomey would not name it a return to regular. That in all probability won’t ever occur. “And that is okay,” she says. “We speak about how fragile life is, and the way it can change so quick, and the way we actually recognize what we’ve got – having the ability to get up every single day, having the ability to collect collectively. That appreciation, that may by no means be forgotten.”

The Deception Go Bridge connects Whidbey Island to the Washington state mainland. Because the U.S. reaches the grim milestone of 1 million COVID deaths, small, rural well being care programs just like the one on Whidbey Island proceed to really feel the pressure of the pandemic.

Lynn Johnson

disguise caption

toggle caption

Lynn Johnson

The Deception Go Bridge connects Whidbey Island to the Washington state mainland. Because the U.S. reaches the grim milestone of 1 million COVID deaths, small, rural well being care programs just like the one on Whidbey Island proceed to really feel the pressure of the pandemic.

Lynn Johnson

For those who or somebody you realize could also be contemplating suicide, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (En Español: 1-888-628-9454; Deaf and Onerous of Listening to: 1-800-799-4889) or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.